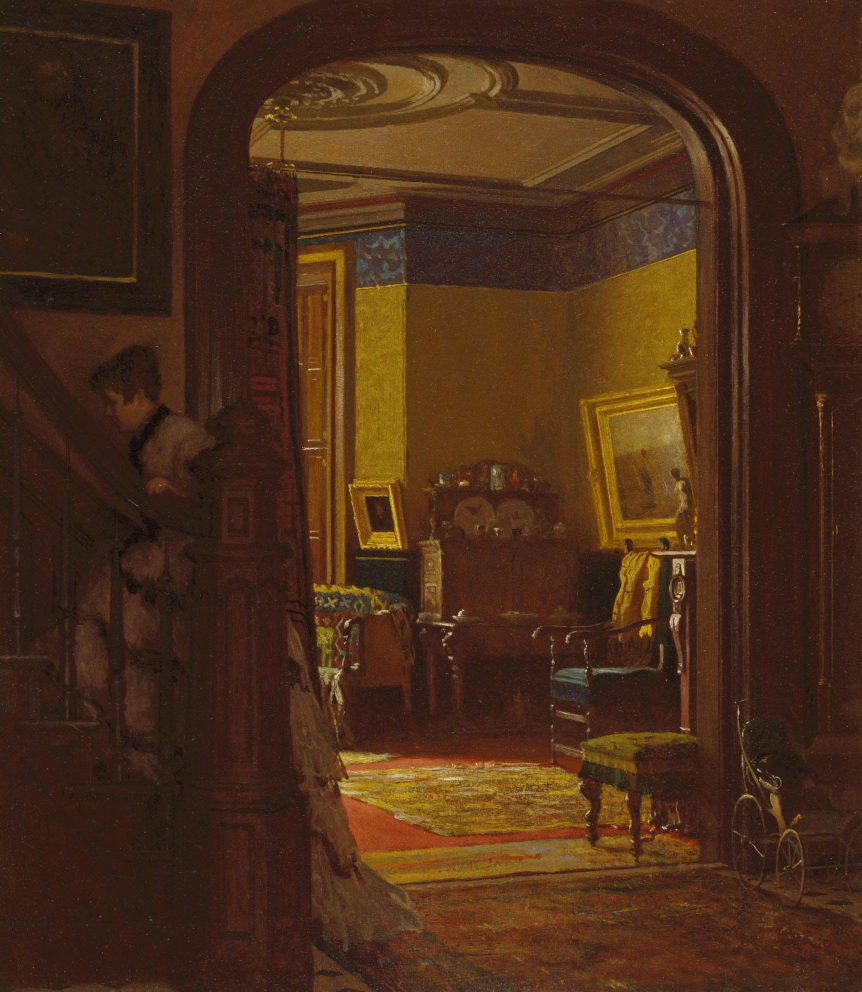

Not at Home by Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), c. 1873. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Gwendolyn O. L. Conkling.

In perusing a recent copy of the online publication Common-place we came across a delightful article titled “House of Cards: The Politics of Calling Card Etiquette in Nineteenth-Century Washington,” detailing the ins and outs of what might be considered an early form of social media—one that could influence politics, society, and even foreign policy. Here, the author, Merry Ellen Scofield, an editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, tells us more, but to get the whole scoop, be sure to visit common-place.org.

Can you briefly recount the origin of calling cards?

Americans did not invent calling cards or calling card etiquette. Popular lore gives that honor to China. So did British traveler John Barrow, who, after an extended stay in Asia, wrote in 1804 that “visiting by tickets which, with us, is a fashion of modern refinement, has been a common practice in China some thousand years,” the only difference being the size and color of the cards. In China, the higher the rank, the larger and more colorful the card. The “ticket” of the

“old Viceroy of Pe-tche-lee,” Barrow wrote, contained enough “crimson-coloured paper” to cover a wall.

Calling cards had reached Europe by the late sixteenth century. In 1884 historian Horatio F. Brown discovered a cache of Venetian examples ranging in date from then into the nineteenth century and determined that calling card etiquette was “a serious duty in the social life of the Venetian nobility. On every conceivable occasion…a family was expected to leave cards on all its acquaintances, and these visits had to be returned.” The custom reached England by the 1700s, where, in the middle of the century, families commonly just used an old playing card, printing their name and a short note on it. The practice of leaving a card in lieu of an actual visit reached Paris by at least 1770 and was firmly established by the time the United States became a country. Thomas Jefferson used cards as America’s minister to France in the 1780s.

Do you think the lady, thought to be Elizabeth Johnson, in Eastman Johnson’s Not at Home might have expected a calling card rather than a ring of the doorbell? And would she have had a servant to accept a card?

Calling cards were not the sole property of city and capital elite. Anyone who participated in polite society carried and used cards. In 1862 a printer sold visiting cards, “plain and fancy,” to the four thousand residents of Vincennes, Indiana. Calling card society was at its height in the period depicted in Not at Home. Servants always answered the door, not the mistress or master of the house, so here we see Elizabeth Johnson removing herself to her private quarters before the servant reaches the door. When told that the mistress was not “at home,” the visitor would leave her (or his) card with the servant and depart. It was understood by all that “not at home” meant not receiving, and not physical absence. The visitor was probably happy to move along with her rounds, unimpeded by an actual chat in the parlor. Having re ceived the calling card, Mrs. Johnson would, within the week or so, return the visit.

How long did the practice continue in the United States?

In Washington, and despite the government’s growing size, many women, even in the 1930s, believed in the importance of calling card etiquette, which embodied their role in society, in politics, and in their marriages. In 1933 the Washington Post featured an article headlined, “Capital Has a Rigid Calling Card Code: Social Ostracism Is the Penalty Paid by Women Who Break It.” Within ten years, though, the system had, as Katherine Graham put it, “happily…fallen by the wayside.” The reason was World War II. Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor more than seventy thousand people flooded into the capital, and that was just the beginning. The subsequent explosion in population and government made first calls to those of higher rank virtually impossible, destroying the foundation on which Washington’s calling card etiquette was based. In addition, circling the city making visits slowly lost its appeal to women, who were beginning to re-evaluate their roles in society.