They called her the “sculptor of horrors.” In Paris, her contorted figures were exhibited at the Maison de l’Art Nouveau, critiqued by Auguste Rodin, and included in the 1903 Salon. Her work was “of the soul,” Meta Vaux Warrick said, “rather than the figure.” When W. E. B. Du Bois recruited her, then in her early twenties, to assist with the “Negro Exhibit” for the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, he wasn’t interested in twisting bronze sculptures heavy with symbolism. Du Bois, and Thomas Calloway, special agent for the exhibit, had something more practical in the works—a historical tableau.

Du Bois’s request was not the first time Warrick—who added the surname Fuller when she wed psychiatrist Solomon Fuller in 1909—felt a tension between her passion and what was expected of her. Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was born into an African American middle-class Philadelphia family in 1877. Her mother, a beautician, and her father, a barbershop owner, prioritized her education in the arts. She attended the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) before continuing her studies in Paris in 1899. A young and unchaperoned woman in a foreign city, she quickly found a home within the symbolist movement. Her sculptures, inspired by ghost stories and the dark interiority of the human spirit, earned her the sculptor of horrors nickname. Yet, time and again, she was told the blackness of her skin must be more obvious in the product of her hands.

When she returned to Philadelphia in 1903, she quickly learned that if she wanted to have any future as an artist in America, she would have to continue to meet requests for race-based work from the leading Black scholars, activists, and luminaries who controlled the commission pipeline. In 1907 she became the first African American woman to receive a US government commission when she was called on to create progress-themed dioramas for Jamestown’s tercentennial. Six years later she created another work marking a historical event when she was commissioned to create a sculpture for the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation.

These pieces required Fuller to submit to expectation, pushing the symbolist style that had earned her attention and accolades in Paris to the periphery of her portfolio. Renée Ater, author of Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller (2011), told us, “the rejection must have been devastating.”

As she pressed herself into the mold Du Bois demanded, the artist also conformed to society’s expectations of a proper middle- class African American woman. After a lengthy courtship, she married Fuller, the first person of African descent to practice psychiatry in the United States, and moved with him to the small city of Framingham, Massachusetts. She began building two parallel lives; one as a wife, and, in time, a mother, and another as an artist. Her husband discouraged mixing the two, so she devised ways to keep them separate: carving out space for herself as an artist—first setting up a studio in the attic of her Framingham home, and later by financing and building a studio down the street, hiding it from her husband for as long as possible to avoid him undermining her plans.

While Du Bois called Fuller “one of those persons of ability and genius whom accidents of education and opportunity had raised on a tidal wave of chance,” it was not as the sculptor of horrors that she would be remembered in art-history textbooks, nor for the patronage of Du Bois. Rather, she is known for her supposed role in an iconic and pivotal movement that shaped Black America in the twentieth century: the New Negro Movement, better known today as the Harlem Renaissance (a term that speaks to the nucleus of the movement, but does not encompass its entire geographic scope).

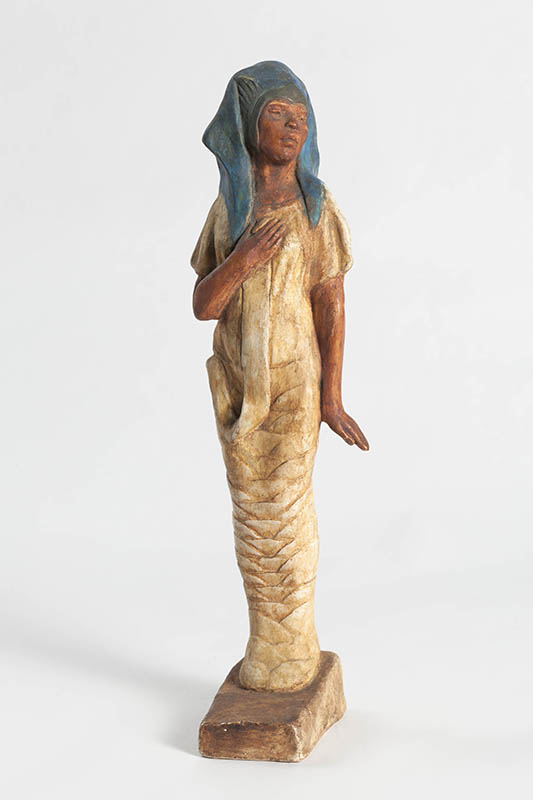

Fuller’s sculpture was not unreservedly admired by her peers. In his book The New Negro (1925), critic Alain Locke dismissed the bulk of Fuller’s work as “imitative and not highly original.” He saw her expression of racial identity as “only experimental”— for him, an insult. And yet, in Locke’s view, there was one saving grace in Fuller’s portfolio: the statue Ethiopia Awakening, which, to his mind, revealed where race-based work could go if guided toward “representative group expression.” It was, he wrote, “outstanding.”

The appeal of the piece to Locke is unsurprising. In depicting a female Egyptian mummy, alive and well, holding the end of her partially unwrapped bindings, the work mani- fests Fuller’s love of symbolism while overtly referencing the twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt, the era of Black pharaohs. Ater is confident that Fuller was influenced by stories of archaeological digs published at the time in The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP. It’s likely she also visited the MFA Boston to see Egyptian artifacts for herself, Ater says. “The most brilliant period, perhaps of Egyptian history,” the artist said, “was the period of the Negro kings.”

The New Negro Movement was at its zenith when Locke’s book gave it a name. Far from Harlem, Fuller worked on the periphery of the movement, and yet her “outstanding” sculpture was employed by Locke as both a spark for and an emblem of it. In so doing, he took some creative liberties. In her research, Ater found that Locke not only misdated the sculpture, but even renamed it to better fit his narrative. Fuller called it simply Ethiopia, but Locke made it what he needed it to be. “We make objects do what we want them to do.” Ater says, “This is not an unfamiliar story.” “The misdating has led us to believe that she created it as the opening salvo of the Harlem Renaissance, but not really,” Ater adds. Rather, it was commissioned earlier in the 1920s for a festival celebrating the contributions of “immigrants” to the nation (the inclusion of African Americans as immigrants is a grotesque piece of historical erasure). Locke’s title, Ethiopia Awakening, implies that the figure is unwinding her own wrappings, freeing herself from imposed constraints. Perhaps Fuller’s simple Ethiopia evokes something closer to her own experience: a woman, half-wrapped, half-bound—by societal expectations, by custom, by time itself—unable or unwilling to reject societal expectations, but equally uninterested in fully succumbing to them.

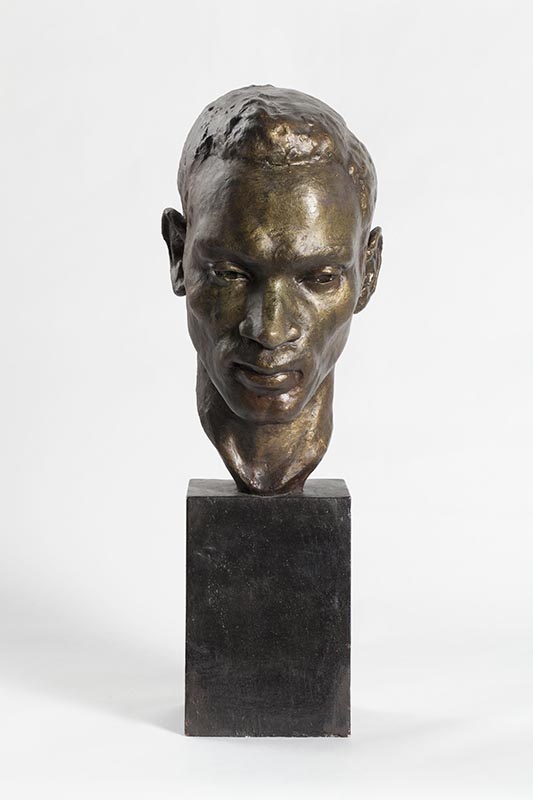

Much of Fuller’s early work, and nearly all the work she did in Paris, was destroyed in a 1910 warehouse fire. What remains are decades of work in plaster, bronze, and on paper that meld together symbolism and the focus on racial issues she was expected to maintain. In Memory of Mary Turner: As a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence was done as a direct response to a 1918 lynching. Talking Skull, from 1939, shows an African man in conversation with an ancestor. Bust of a Young Boy, a likeness of her son, Solomon Fuller Jr., created in 1914, stands as a testimonial to Fuller as a mother, while the face that gazes out at the viewer carries the stoic calm of a Black pharaoh.

The debate over what it means to be a Black artist and to create work within a race-based narrative neither started nor ended with Locke. In 1988 New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman asked, in a review of a show of work by Black artists, “What, if anything, distinguishes black painting or sculpture from any other kind of art?” He continued: “No doubt, most of these painters and sculptors prefer to be thought of first as artists and not primarily as black.” Kimmelman’s question is the same one Locke had hoped to obviate by encouraging more work like Ethiopia Awakening. And yet, we find ourselves inclined toward Fuller’s perspective that a shared lived experience need not manifest itself uniformly in art. Creating while Black was her activism, and the renaissance in Harlem didn’t need to roll into Framingham for her to assert through her art that she was powerful.

The work of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller isn’t particularly well known outside of the world of American sculpture, but it should be. Fuller’s pieces periodically come up for auction and private sale and typically sell for under $10,000.

To understand an artist, one must see their work. Much of Fuller’s is held privately, so Jessica Roscio, director of the Danforth Art Museum—home to the largest collection of Fuller’s work and related materials—encourages future collectors to consider putting their acquisitions into the public sphere, whether on loan or as a gift. The pieces that can be seen, Roscio says, “represent a period of art history that is not as well studied or understood” as the work of earlier African American sculptor Edmonia Lewis, or the artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

We feel compelled to wonder where Fuller’s work would have gone had she stayed in Paris, where she was better supported in her resistance to gender norms and race-based expectations. What art would she have left behind without her husband’s decades of dismissal; without Locke’s distortions; without Du Bois’s redirections; without the 1910 fire? What she has left us is beautiful and important, yet the shadow of possibilities dims the brilliant glow. Shortly after she returned to America from Paris, Ater says, the artist received a letter that rings with melancholy from a friend, who wrote: “You never should have left.”