Baltimore’s history, spunk, and cultural richness make it unique. This magnificent city is having a tough time now, and as it struggles to get some traction going up rather than down, its two anchor museums are more than pulling their weight. The Walters Art Museum and the Baltimore Museum of Art are among America’s finest. Their collections and cultural value are world class. They present unusual and complementary contrasts, too.

The Walters is as eclectic as Baltimore. It started as the collection of a father and son, and that’s still its foundation, but what collectors they were. William T. Walters (1819–1894) was a prosperous Baltimore merchant with liquor and railroad interests who sat out the Civil War in Europe, buying art. His son, Henry Walters (1848–1931), was a bon vivant who shared his father’s taste for high culture. Booze, money, and travel: perfect to lubricate a quest for good art. Upon Henry’s death in 1931, he left the art and some endowment money to the City of Baltimore, in retrospect a leap of faith that seems unfathomable today, given the city’s choppy trajectory.

Both William and Henry Walters had allowed the public to view their collection from time to time, and in 1909 Henry opened a purpose-built palazzo-style building to house his art in the Mount Vernon neighborhood, overlooking the city’s Washington Monument. It was then, and is still, a jewel in Baltimore’s crown. The place has expanded but it’s still intimate. Architecturally, it’s an elegant temple of culture.

Last year, after a meticulous $10.4 million restoration, the Walters re-opened one of its adjunct buildings: a Greek revival mansion at 1 West Mount Vernon Place, dating from the early 1850s. It’s a breathtaking space, but more on that later.

The Walters exudes Gilded Age taste and style. Henry Walters collected the best of everything. There’s the splendid Madonna of the Candelabra by Raphael and many other fine paintings, but also distinguished antiquities, Thai scrolls and banners, outstanding Sèvres porcelain, and some of the best Islamic art in America. It owns rare books, illuminated manuscripts, and irreplaceable old textiles. For good measure, there’s Manet, Monet, and Turner. Its closest European counterparts are the Burrell Collection in Glasgow or the Jacquemart-André Museum in Paris. Personally, I think of it as a dollhouse Victoria and Albert Museum. The collection is that good, but the place never overwhelms.

Farther north off Charles Street, the Baltimore Museum of Art has a different vibe, history, and trajectory. It was founded as a public museum in 1914, and it’s bigger than the Walters. Members of BMA’s original board of trustees and, for many years, its leading donors came from the ranks of Baltimore’s broad- and civic-minded Jewish community.

I don’t sense even a whiff of exclusivity at the Walters. When I visited, it was bustling with a refreshing mix of people. While the Walters collection has expanded, it still has the stamp of the Walterses’ distinct taste. The BMA has something for everyone and works to cover many bases. I’d describe it as edgy and modern to the Walters’s Old World feel.

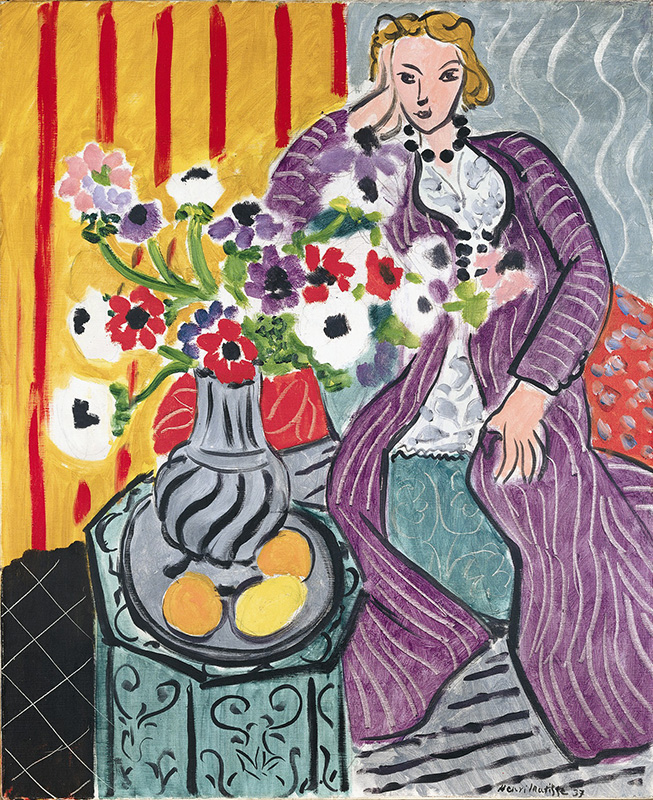

One of the highlights of the BMA is the collection of works by Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne, and Degas assembled by two local sisters, Claribel and Etta Cone. It’s art of startling beauty and importance. These women had good taste and money, a rare combination, and bought the best new French art long before snobby French collectors wanted it. There are great collections of Old Masters and of American and African art there, too. The BMA has a smashing collection of ancient mosaics from Antioch. The building is both lovely and bracing, a clean neoclassical pile designed by John Russell Pope and harmoniously expanded.

The two museums are dynamic, with strong, committed boards. The BMA has a talented, young, and energetic new director. The place is brimming with initiatives. They’ve made it a community hub in the best possible sense. The collection is growing stronger and stronger in the work of living artists, too. This new art is bringing in hip young people in addition to the old faithful from Baltimore’s suburbs. Everyone has something to be excited about in this impressive community of artists. It’s a nice combination of a traditional, civic museum and a laboratory for learning.

The Walters is an experimental place, too. It’s treating 1 West Mount Vernon Place as a work of art. The interior is gorgeous and has to be one of the most elegant domestic interiors in the country. The museum is using the space in a very clever way. Most of it is free of furniture, focusing the eye on its splendid moldings, fireplaces, sweeping staircase, and Tiffany skylight.

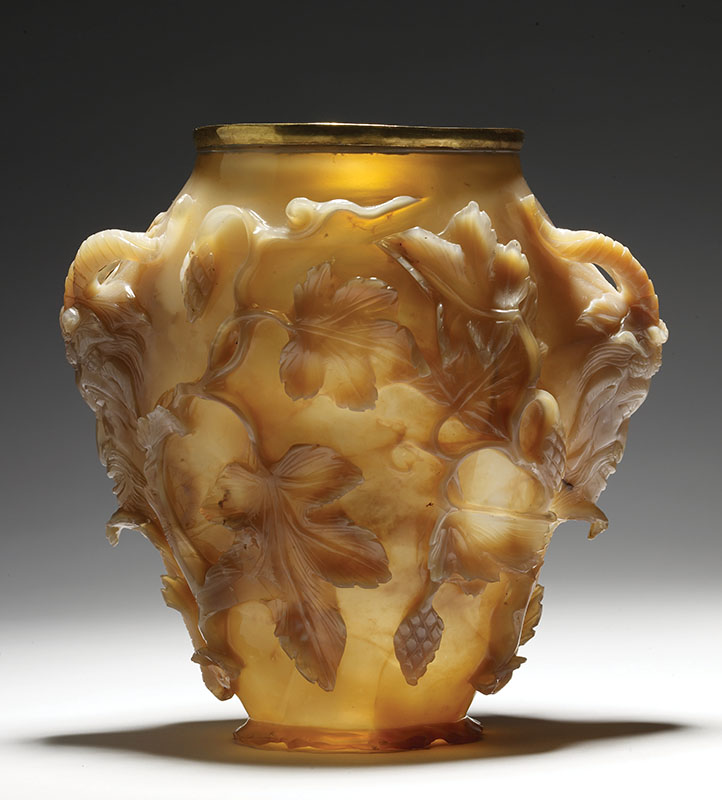

The art displayed there is mostly the very best of what I call “breakables”—in the case of the Walters the finest ceramics, glass, and porcelain from many ages and places. Sorry to offend, but I was a paintings curator. I was riveted by the vibrant ceramics, from ancient Syrian pieces to Chinese vessels with silky, gleaming glazes, French rococo porcelain, and some contemporary, specially commissioned work, all in conversation and set in Georgian spaces.

When I visited, both museums had impressive shows. The BMA had a great exhibition on surrealist art called Monsters and Myths, which had debuted at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, as well as a moving show of art by Baltimore schoolchildren. I saw the Matisse/ Diebenkorn show there a couple of years ago and a John Waters show, both excellent. The museum is also organizing promising exhibitions on African-American art.

The Walters had a fascinating focus show on its “Silk Book,” a silk prayer book that was a marvel of the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris. One of the technological wonders of the time, it’s a unique, entirely woven book. The Jacquard loom that wove it was programmed, like an early computer, using some five hundred thousand punch cards directing the complex pattern. The tiny show was sublime.

“Pride,” a wise person told me many years ago, is best described as “the expectation that good things will happen.” I have found this to be a profound truth. So with these two great museums stewarding the city’s cultural future, how could anyone not be proud to be a Baltimorean?