For centuries now Venice’s amphibious condition, the uncanny way in which it rises, spectral and pale, out of the alien element of water, has captured the imagination of the world. A new exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC, Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano, does justice to that condition, even if it sometimes feels like two shows rather than one. The first is devoted to the American painters who flocked to the city in the final decades of the nineteenth century, together with the writers Henry James and Edith Wharton and the patrons Isabella Stewart Gardner and Leland Stanford. The second examines the virtuosic glasswork produced on the island of Murano. These two subjects converge, it is true, in the condition of Venice itself, in that intuition of decay that attracted John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler to Venice, and in the fact that a revitalized glass industry would help to lift the city out of its fallen state.

When Whistler and Sargent arrived in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, they encountered a very different place from either that “white swan of cities” that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had seen more than half a century earlier, or that “pink and pearl” city (in Oscar Wilde’s phrase) whose wraithlike enchantments inspired some of J. M. W. Turner’s finest works. By this point, Venice had borne the brunt of Austrian overlordship and the pains of Italian unification, as well as the evisceration of its manufacturing base, such as it had been. That one of the cultural heroes of the day, the death-obsessed Richard Wagner, perished in the Ca’Vendramin Calergi in 1883 only deepened those morbid associations that would achieve their fullest expression in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice.

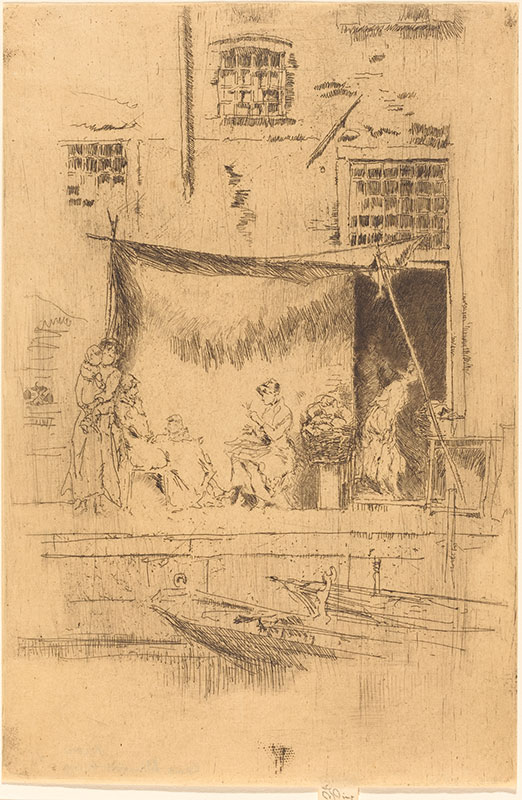

Fig. 4. The Beggars from the Venice, a Series of Twelve Etchings series by Whistler, 1879–1880. Etching and dry point on laid paper, 12 1/4 by 8 3/4 inches. National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection.

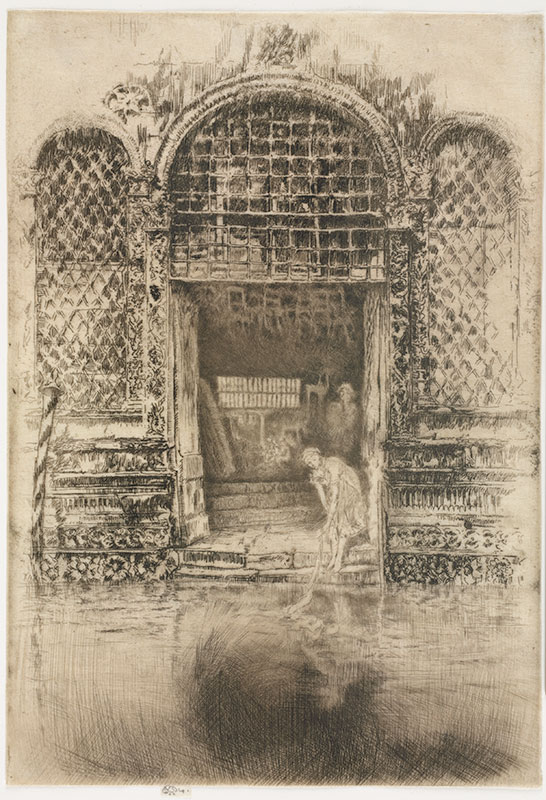

What Whistler and Sargent sought differed as well from what Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet found, despite the fact that their visits overlapped. The impressionists—surely among the most well-adjusted painters of the last two hundred years— discovered beauty everywhere they looked, even if, raised as they were in realism, they never succumbed to the reverie that defined Turner’s works. Whistler and Sargent as well emerged from the realist movement, but to very different effect. Drawn to the purely formal play of light on water, Renoir and Monet took little interest in the modern life of Venice. For their American compeers, however, Venice was a city in decay, sinking into the squalid waters of the lagoon. In such etchings as The Beggars, Fruit-Stall, and The Doorway (Figs. 3–5), created during Whistler’s first visit in 1879 into 1880, he depicts a Venice that is new to art, one in which plaster falls in clumps from the ancient walls, whose exposed brick has rotted away through centuries of exposure to salt water.

Whistler’s gaze is not entirely unsympathetic; it is more neutral than anything else. As for Sargent, whose visits coincided with Whistler’s, his depictions of modern Venetian life are even more assertively realist, although, as always with this artist, he cannot help finding the glamour in every scene he paints. Thus the three women in Leaving Church, Campo San Canciano, Venice (Fig. 7) are suspiciously charming as they brace themselves against the cold, and despite the spareness of the campo through which they pass, one would be happy to be there with them.

Whistler and Sargent were only the most illustrious American painters to descend on Venice at the turn of the last century. By the dozens these artists came, with their unequal gifts, to pay homage to the ancient city. Robert Frederick Blum—a painter who deserves to be better known—mines a similar vein to Sargent’s in his Venetian Lacemakers of 1887, with the lurching diagonal tilt of its composition and the attention to such details as the shimmer of glass in the windowpanes (Fig. 10). Walter Gay’s splendid Interior of Palazzo Barbaro, Venice (Fig. 6) is yet another of his interior scenes of wealth and privilege, resonantly voided of human inhabitants.

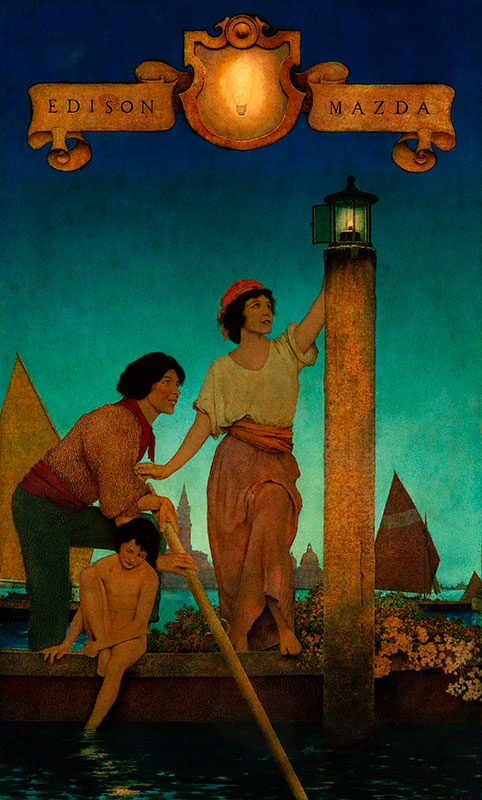

Very different are the dreamscapes that Maxfield Parrish composed for the consumption of Americans who would probably never get to visit Venice and thus would know it only through veils of myth. Painted for the annual Edison Mazda calendar, his Venetian Lamplighters of 1922 is a deep blue evocation of twilight, depicting three Michelangelesque figures rising before an expanse of water (Fig. 11).

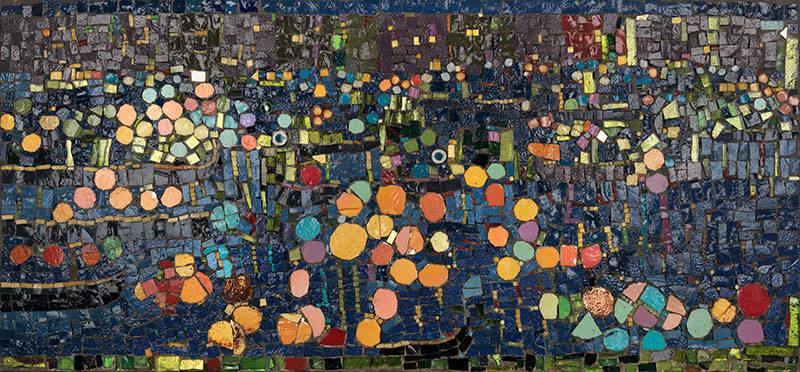

But perhaps the most extraordinary work in the entire show is Maurice Prendergast’s Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice of about 1899 (Fig. 1). Using glass and ceramic mosaic tiles set into a plaster ground, Prendergast has essentially created what may well be the first abstract image ever made, a decade before the abstractions of Hilma af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky.

His inspired use of glass underscores the vital role that the material has played for centuries in the cultural and commercial life of Venice. When the city was finally assimilated, through the plebiscite of 1866, into the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, its fortunes were at their lowest ebb in a thousand years. Of the many reasons for this near collapse, not the least was the fact that one of the city’s most established industries, the manufacture of glass, had all but died out. Centered on the island of Murano for centuries, Venice’s glassworks would be revived largely through the efforts of one man, Antonio Salviati, a young lawyer from Vicenza, and through that revival, it would play a crucial part in the revival of Venice’s fortunes. In 1866 Salviati teamed up with the British ambassador and scholar Austin Henry Layard to manufacture glassware, and in 1877 they founded the Compagnia Venezia Murano, which was soon employing hundreds of workers and winning medals in the sundry Expositions Universelles of the day, even as it opened shops in London and Paris. The company initially produced mosaics and was responsible for the facade and interiors of Stanford University’s Leland Stanford Jr. Memorial Church.

Soon, however, it had shifted its focus to creating the small-scale sculptures and goblets that have made Murano glass famous throughout the world. Today we encounter so much of this glass in the shops along the Merceria and the Rialto Bridge, and at such modest prices—at least relatively speaking—that we are apt to take for granted their astounding aesthetic achievement. One collector who was especially smitten with them was John Gellatly, a New York businessman who bequeathed more than sixteen hundred works of fine and decorative art to the Smithsonian Institution. From his collection come a number of the pieces of Murano glass that appear in the present show. The most striking thing about his conical goblet with an entwined serpents stem (Fig. 9) and his Fenicio goblet with swans and an initial “S” (Fig. 2) is how, at one and the same time, their tendrilous stems and the fragile, fantastical threading of their handles look back through the rococo to mannerism as well as forward to the styles of today. The blue and gold marbling of the latter chalice, no less than the pale green leaves and the red and blue bow of its mid-section, point to another outstanding property of this glass: left to its own devices, this most fragile of commodities is almost imperishable. One and a half centuries after its creation the colors shine forth with all the saturated richness that they received at the very instant of their creation. And through their conjunction of fragility and beauty and unlikely survival, they could almost stand as emblems of the city that gave them birth.

Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum to May 8, 2022.