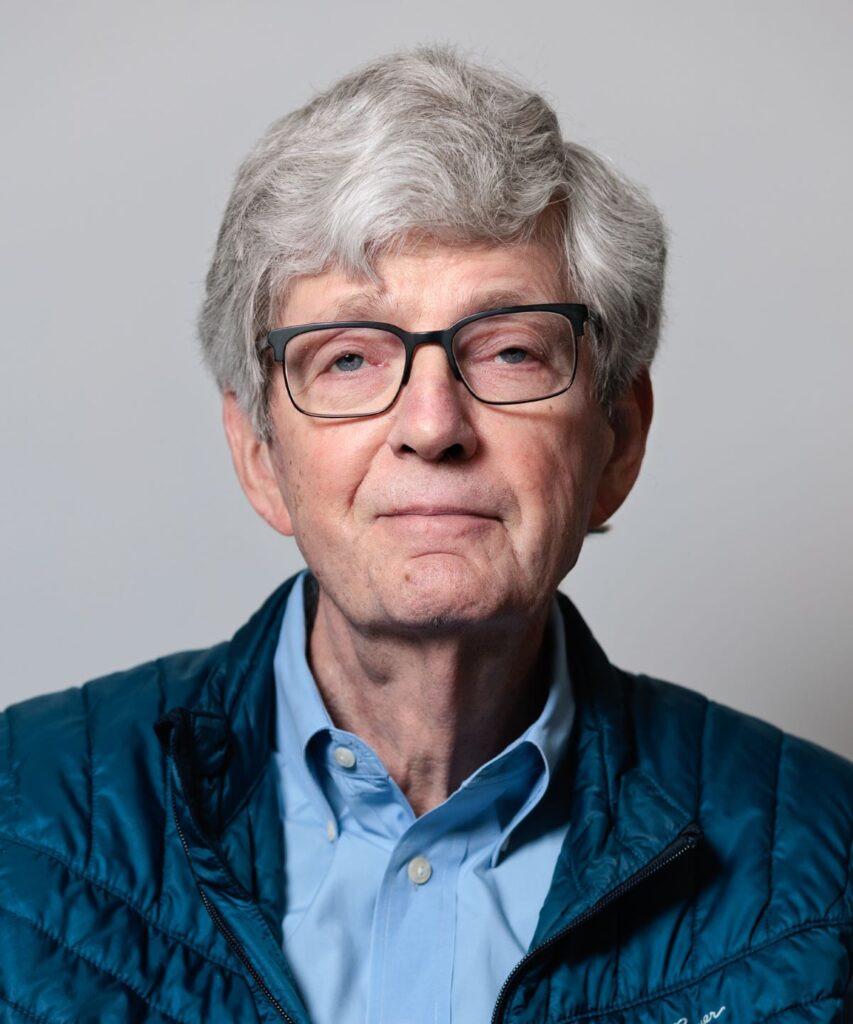

In retrospect, Robert Brunk’s career as an auctioneer seems as unlikely as it was foreordained. From a family of midwestern Mennonites, the former divinity student—who also spent time as a social worker, teacher, farmer, and woodworker—drifted into the antiques business in Asheville, North Carolina in the late 1970s. He founded Brunk Auctions, now a regional powerhouse directed by his son, Andrew, and daughter-in-law, Lauren, in 1983. In his new memoir, A Question of Value: Stories from the Life of an Auctioneer, the gavel-wielding philosopher shares wisdom gleaned from his many years on the road and in the salesroom. His empathetic tales capture the comedy, pathos, joy, and ultimate mystery that is collecting. As Brunk has learned, it is never just about the stuff.

–Laura Beach

The language was hobbled and fused into new words: “Now would you bid?” became nominabid.

“Do you want them at?” became wanamat.

Photography by Reggie Tidwell.

“Will you bid?” became willybidda, erdabid, or illabider. “Do you want them for five?” became wanamafive.

“I believe I would” became blevawood.

To string the words and numbers together in a smooth line also required cadence and the sound nuh (now) to create syncopation; thirty, thirty, thirty, nuhthirty, thirty. Sixty became sickity, seventy became senny, smoothing out the nonmelodic consonants and wrong-syllabled words. It helped me to understand this as a form of music: the rhythm and cadence as the ground, the words as a melody of sorts, sung allegro (fast and lively) or as an ostinato (a short repeated pattern). Senny, senny, senny nuh senny, no eighty, no eighty, noweighty, noweighty, say eighty, nuh niney, niney niney nuh niney, wanamat niney, hunnert, hunnert, hunnert nuh hunnert, say hunnert?

To become a licensed auctioneer in North Carolina, I had two choices: apprentice with a licensed auctioneer for two years or take a two-week course at an accredited auction school, either of which would qualify me to take the licensing exam. I had chosen an auction school because it was faster and now, the fall of 1982, found myself seated with thirty-five other students.

I had been a student at Princeton Theological Seminary for a year, earned a graduate degree in social work, taught sociology at UNC Asheville for four years, and been a farmer and woodworker, but now, at the age of forty, the auction business looked like the best fit so far for my interests and aptitudes. But I was not searching for existing agencies or employment possibilities. I wanted to create something of my own invention—a new way to define myself—and live responsibly in this world. I anticipated careful research, creative marketing, improvised theater, long hours, inevitable failures. I was eager to throw myself into a new challenge and embrace its mysteries and risks.

Auction school encouraged the mystique of the chant, the singsong, fast-talking style of calling for bids. State and national auctioneer championships were based on the smoothness and uniqueness of the chant. In the rural South, the auctioneer is part cowboy, farmer, old-fashioned horse trader, con man, and, above all, preacher. The auctioneer’s chant is close to rhythmic Pentecostal preaching, the “uh” after many words: “The time-uh for salvation is now-uh.” At auction school, hours were spent learning to talk quickly. We were handed a microphone wrapped in a red bandanna and instructed to count backwards from $165.00 in $2.50 increments as fast as possible, evenly, and without hesitation.

As I traveled in my car or truck, I sold cows, streetlights, fence posts, interstate signs, and tires, always ending by singing, “And I sold it for a thirty-dollar bill” to a long-remembered sequence of notes in Gregorian chant, closer to my taste in chants. I would make each utility pole or every third white center line a bidding increment so that turns and intersections required adjusting the cadence. I played tapes of national champion livestock auctioneers; the best were clear, percussive, melodic.

Evenings at auction school, students would gather and discuss the day’s session. Most were men, one a Black minister hoping to raise money for his church. Some wanted to become contract auctioneers for added income on weekends. Others focused on selling real estate or livestock, or on opening a general merchandise Friday night auction. Several clearly struggled with a lack of sustaining resources. All, like me, were considering a substantial shift in their lives.

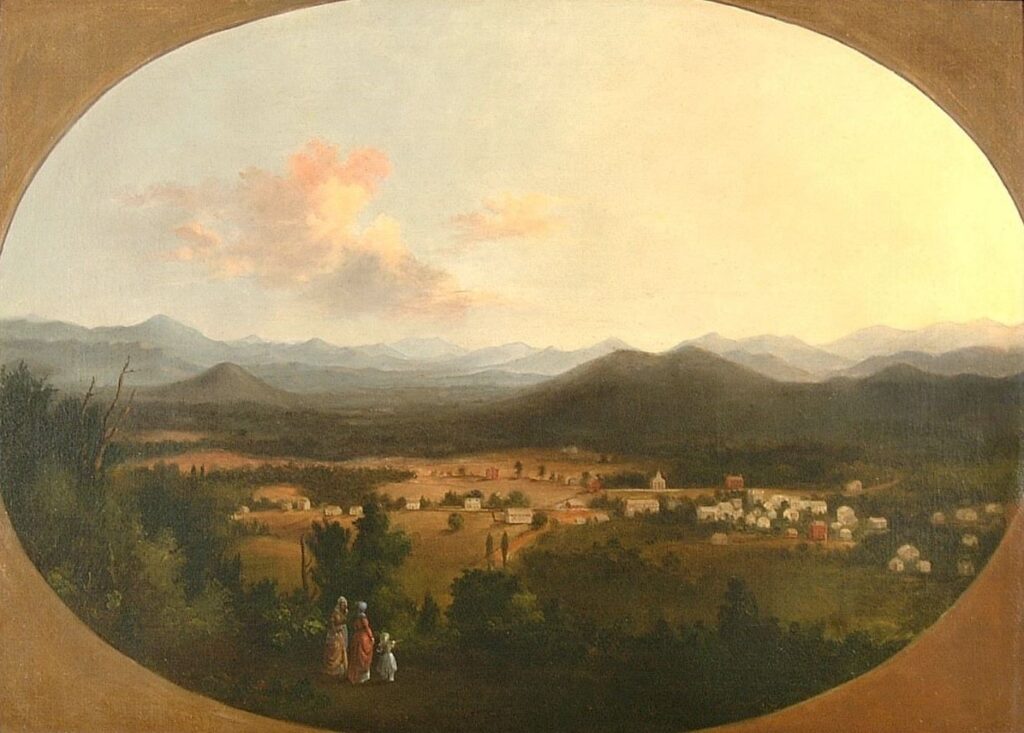

At the time, our family lived on our mountain farm north of Asheville. Four or five students in auction school with rural backgrounds reminded me of several of our neighbors on Sugar Creek. They lived close to the ground and were ready to help, solid and steady. My kind of people.

As the parade of professional auctioneers rolled through the days at auction school, I learned many responses to stalled bidding—words to cajole, flatter, scold, or encourage when the bidding stopped. I liked these phrases; they personalized the proceedings a bit and offered opportunities for friendly humor. Depending on the setting, I used variations of these for many years:

Stay with me now.

That lady knows what she’s doin’. You were doing so well.

We’re selling it, not renting it.

You’re allowed to bid twice, you know. Think of this as a great anniversary gift. It’s your turn.

Don’t go home and say there weren’t any bargains.

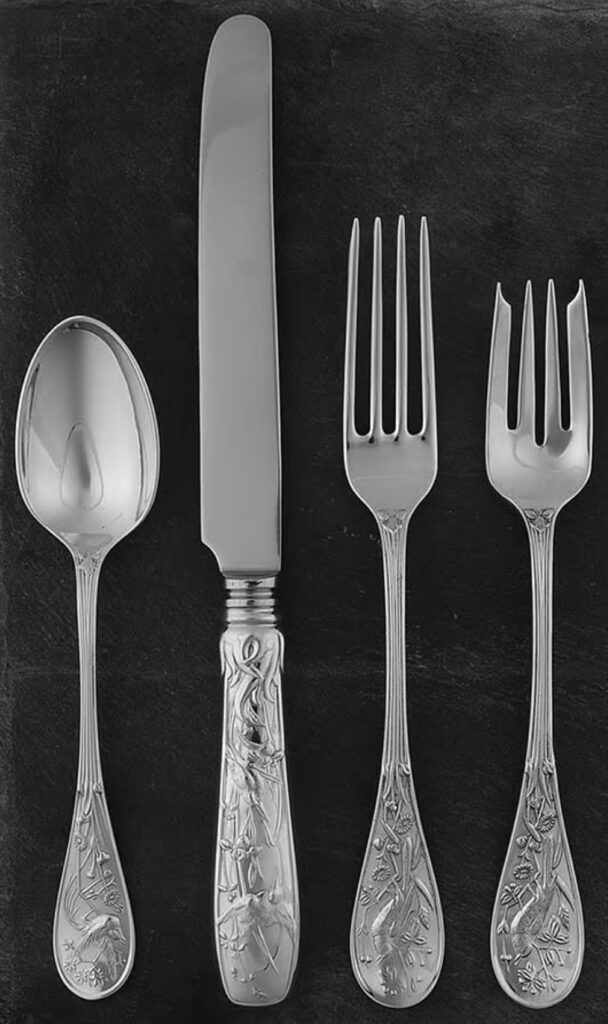

One session at auction school was led by an attorney who explained the basic elements of contracts so we would be prepared for questions about them when they appeared on the state licensing exam. Bid calling and bidding create legally binding oral contracts. “Would you pay one hundred dollars for this item?” If the answer is “Yes,” in whatever form that takes, a contract exists. Mortgages, tobacco, livestock, fine jewelry, cars, US Treasury bills, heavy equipment, real estate, and wheat futures are all sold at auction, each industry with its own rituals and carefully honed signals and vocabularies. Most of these specialized auctions are attended by professional buyers, usually not the general public.

In the years that followed my time at auction school, I learned that bidding at auctions can take many forms: the slight nod, the anxious wave, the touched nose or ear, the twitched finger. Stories like the one about the man who waved at a friend and bought a painting for $5 million are amusing but rarely based on real events.

Some auction goers take delight in bidding on expensive items but are careful not to buy anything: bidding as a public display. Others try to conceal their bids: bidding as a covert maneuver. Some bidders bid often but rarely buy anything: bidding as bottom-feeding. Occasionally, a bidder, as a lifestyle, is unable to come in second in any setting: bidding as personal confrontation. On rare occasions, a bidder is not focused on exactly what they are bidding on or on what they end up buying: bidding as blind entertainment.

One morning at auction school, our guest instructor, an award-winning machinery auctioneer, tall and confident, asked us to pretend we were in a live auction. As he began his melodic chant the students were slow to begin but soon jumped in as the bids climbed to the low thousands. The numbers were very close together and required careful attention to know exactly where the bidding stood.

At one point, a young man wearing a green cap raised his hand to bid $2,800 on an imaginary hydraulic jack for a truck. In an instant, as he began to lower his hand, his bid became $2,900. He jumped to his feet and began waving both his arms. He yelled at the auctioneer, saying that he had not bid $2,900.

He was adamant and stayed on his feet, still waving, until the auctioneer finally stopped the auction. The auctioneer, clearly annoyed at being interrupted, pointed at the young man and asked, “You were bidding, weren’t you?” his voice an act of authority and condescension.

The young man shouted his response, saying, yes, he was bidding, but he did not bid $2,900.

The auctioneer replied, “After you do this a few years, you will see how it works. You have to learn how to work the crowd.” The young man stood his ground, rooted by his anger, a prophet in the wilderness, even as the auctioneer resumed his chant.

As the auction continued with no further discussion, I silently cheered for the young man. This session was intended to demonstrate an example of a flawless chant, but for me, it illustrated the sort of auctioneer I did not wish to be, one who pushed the edges of legitimate bidding. An old country auctioneer once proudly told me he could get three bids off a slow bidder, one when their hand started up, one when it got to the top of its motion, and one on the way down.

I wished for more training sessions in which I heard the words “trust,” “values,” “accuracy.”

The last night of auction school, we tried out our fledging skills at bid-calling. There were thirty- four student auctioneers (two had dropped out) standing in an alphabetical row. I was near the front of the line and decided to sell my three allotted items in a manner closer to what I imagined myself doing later, a style closer to Sotheby’s and Christie’s auctions, polite, understated, spoken English.

The auctioneer helping the students that night was a tall, friendly gentleman who wore a cowboy hat and boots, a leather sport coat, and a large silver belt buckle; his string tie was anchored by a chunk of turquoise. It was a real auction; there was a room full of people and furniture and household goods to be sold. I was nervous when I stepped up to the podium, as I was not going to reflect the training of the last two weeks.

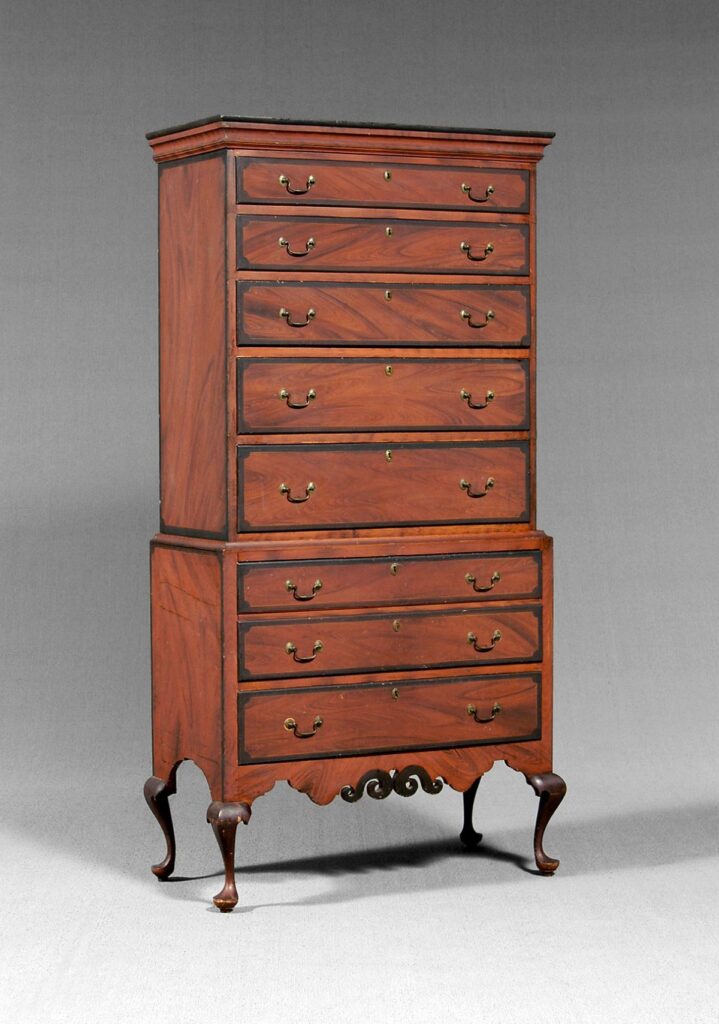

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are pleased to offer this fine mahogany Chippendale-style chair from the early twentieth century. Who will start the bidding at ten dollars?” I began.

My instructor interrupted, “No, no, let’s start over.” He was holding a clipboard and started tapping it against the podium to create a rhythm. “I’ll start adding words, and you join right in,” he encouraged.

“Wanow hunert, hunert, hunert, erdabid, hunert, hunert, say hunert, wanamuh niney, niney, niney, say niney? Erdabid erdabid erdabid, wanamat niney niney nuh niney . . . ?” His chant was polished, smooth, and effortless, and working down from his $100 to $90 was called throwing out the hook, hoping for a bid from an anxious bidder before the bottom was reached. I tried again with my flat words of introduction for the hapless chair, but I was weak and tentative; the chair brought $15.

“Son, I know you’re trying hard,” my coach said, “but you need to work on your chant. You’ll never make it without a good chant. People want to hear it.” He was right: this was not the setting for proper English. I switched styles on my second and third items, a wheelbarrow and a portable air compressor.

I summoned my best syncopated lines from the hours of selling cows and utility poles. I plunged in, calling forth the sacred litanies of the auction gods. I sang and barked and thumped the floor with my foot. I kept the numbers, the nuhs, the wanamas, the erdabids rolling like the rapids on a broad, fast river. I gestured. I pointed at people. I clapped. The words, numbers, and connecting syllables spewed out in long, arching spirals. I pointed at the instructor and told him he could ride this train too. I paused only slightly between the wheelbarrow, which sold for $12.50, and the air compressor, which brought $25.00. I wasn’t able to achieve a steady cadence, but there were short spans when the torrent of words and sounds created rhythmic patterns.

When I finished, one lady in the third row clapped two or three times. One man took off his cap and fanned it, a gesture to cool the overheated air. The instructor put his hand on my shoulder and said, grinning through his large, uneven teeth, “Sheeyit, son, where in thee hell did that come from? You hang onto that, you might make it yet.”

It was the first and last time I would ever sell items at auction with a chant, well intentioned as my efforts had been. I opted for clarity. The speed and urgency of the chant heard in a livestock or car auction were not a good fit for the auctions I envisioned and often left people hesitant to bid, as they weren’t sure where the bidding stood. Was the number the auctioneer repeated over and over the last bid, or was it the bid he was asking for? I hoped my plain words, used thousands of times in the years that followed, would be clear to all present and would identify both the current bid and the next interval.

“The bid is $100. We’re asking for $110. Any interest at $110?”

Or, “The lady’s bid is $300” (pointing in her direction); “any advance to $325?”

But even now, years after auction school, when I see a herd of cows grazing in a pasture, I sometimes silently mouth a few nominabids and sell a couple Black Angus steers.

This article is excerpted and adapted from A Question of Value: Stories from the Life of an Auctioneer, published by the University of North Carolina Press. Copyright © 2024 by Robert Brunk. Used by permission. For more information consult uncpress.org