Fig. 1. Standing female figurine, Mexico, Guanajuato, Chupícuaro, 40–100 BC. Ceramic with pigment; height 3 1/8 inches. Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, Connecticut, courtesy Division of Anthropology, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

The German-born artists and educators Anni and Josef Albers are famed for both their groundbreaking experiments in weaving and painting and their progressive theories of art. To many, the Alberses were the embodiment of forward-thinking modernity. And yet, to a surprising degree, they were inspired by ancient art. They were fascinated by the art and objects made by the civilizations of the Americas before the arrival of the Spanish—pre-Hispanic artifacts, in the parlance of historians. They took more than a dozen trips to Latin America and became deeply committed collectors of ancient figurines, vessels, and textiles. They eventually amassed more than fourteen hundred pieces from Mexico, Peru, and Costa Rica. The Yale University Art Gallery’s exhibition Small-Great Objects: Anni and Josef Albers in the Americas is the first major show to examine the Alberses as collectors, exploring their collection in relation to their own art practices as revealed through their paintings, weavings, photographs, and sketches. The show’s accompanying catalogue delves further into the personal correspondence between the Alberses and colleagues that forms the exhibition’s archival backbone, and offers the insightful reflections of Michael D. Coe, a friend of the Alberses and former curator in the Division of Anthropology at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, where many of the objects owned by the couple now reside.

Fig. 2. Monte Albán ’35/Monte Albán by Josef Albers, 1935 –1939. Gelatin silver prints mounted on cardboard, overall 8 1/8 by 20 inches. Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop, Bottrop, Germany, © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photograph by Tim Nighswander.

Anni and Josef met at the Bauhaus, the German school founded by Walter Gropius in 1919 that was dedicated to forging a unity of art, craft, design, and architecture. Anni began as a student in April 1922, and shortly after met Josef, who was then the head of the glass workshop. During their time at the Bauhaus, Anni developed into a sophisticated weaver, while Josef created paintings and furniture, and honed his signature learn-by-doing educational approach. The rise of the staunchly anti-modernist Nazi party in 1932 had major repercussions for the Bauhaus, and the school was forced to close its doors a year later, leaving the Alberses unemployed.

Fig. 3. Shrine by Josef Albers, 1942. Zinc plate lithograph, 23 by 18 1/8 inches. Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Anni Albers and the Josef Albers Foundation, Inc., © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photograph courtesy Visual Resources Department, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

Fortune almost immediately smiled on Anni and Josef. Black Mountain College, a new experimental school with the making of art at the core of its curriculum, was being formed in North Carolina. At the recommendation of architect Philip Johnson, who had seen the work of Josef and Anni at the Bauhaus, Black Mountain cofounder Theodore Dreier sent Josef a telegram inviting him to join the faculty. In November 1933 Anni and Josef packed their bags with as many artworks as they could fit, and left by ship for the United States.

Fig. 4. Monte Albán by Anni Albers (1899–1994), 1936. Silk, linen, and wool; 57 ½ by 44 1/8 inches. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard G. Leahy, © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photograph courtesy Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

At Black Mountain College Josef developed the art teaching program, while Anni established the weaving workshop. Once they were settled, their eyes turned to Mexico. The Alberses had been intrigued by preHispanic art for many years. In Germany they had visited museums with rich holdings of ancient American ceramics and textiles, such as the Museum Folkwang and likely the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde (now the Ethnologisches Museum). These initial encounters with pre-Hispanic art only whetted their appetite. After visiting Mexico in 1935, their interest in ancient American art developed into a lifelong passion.

Fig. 5. Necklace by Anni Albers, c. 1940. Bobby pins on metal-plated chain; length 18 inches. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Nighswander photograph.

Their first trip took Anni and Josef to the southern state of Oaxaca and the archaeological site of Monte Albán. They would return many times. Perched on a mountain, this ancient citadel was the political and economic hub of the Zapotec civilization for more than a thousand years. Over the course of several years, Josef documented the changing landscape of this site as it underwent excavation in his photo collage titled Monte Albán ’35/Monte Albán (Fig. 4), which includes contact prints taken between 1935 and 1939. In a slightly later lithograph called Shrine (Fig. 5), Josef further abstracted the steep steps leading up to the tiers of a pyramid similar to those found at Monte Albán.

Fig. 6. Necklace from Tomb 7 at Monte Albán, Mexico, Oaxaca, Zapotec, AD 250–800. Gold, coral, pearls, and turquoise; length 17 inches. Museo Regional de Oaxaca, Mexico; photograph courtesy Digital Collections, Yale University Library, New Haven, Connecticut.

Around the same time, Anni also transformed her impressions of archaeological sites into artworks, perhaps most explicitly in the pictorial weaving Monte Albán (Fig. 6). She made this work after her second trip to Oaxaca, and, like Josef’s Shrine, her woven pyramidal designs and horizontal planes echo the layout of the site. She also took inspiration from the cache of jewelry in Tomb 7 at Monte Albán, which included necklaces made from bone, coral, and turquoise (see Fig. 8). These ancient necklaces opened her eyes to the possibility of making jewelry from unconventional materials, and she experimented with household items such as bobby pins (Fig. 7) and sink drain covers.

Fig. 7. To Mitla by Josef Albers, 1940. Oil on Masonite, 21 by 28 inches. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

During their travels to archaeological sites in Oaxaca and Mexico City, Anni and Josef began purchasing small figurines, at first informally, and later with a more systematic approach. They were particularly drawn to handheld pieces, such as the ceramic Chupícuaro figurine in Figure 3. These were especially appealing because they demonstrated several key principles that Anni and Josef explored in their work. Both artists were committed to the idea of truth to materials, meaning that artists should work within the limitations and possibilities of the material at hand. In this case, the Alberses reveled in the fact that the ceramic objects looked like clay, and were not pretending to be any other material. They also appreciated that a humble material like clay could be transformed into such a visually striking image. Formally, they valued the economy of color and overall symmetry, which paralleled such paintings as Josef’s Leaf-green Wall. Finally, just as Josef produced hundreds of paintings that experimented with different configurations of color within the same general form—both in his Variant and Adobe works and later in his Homage to the Square paintings—the Alberses recognized the same serial impulse in the Chupícuaro figurines and collected about three hundred of them.

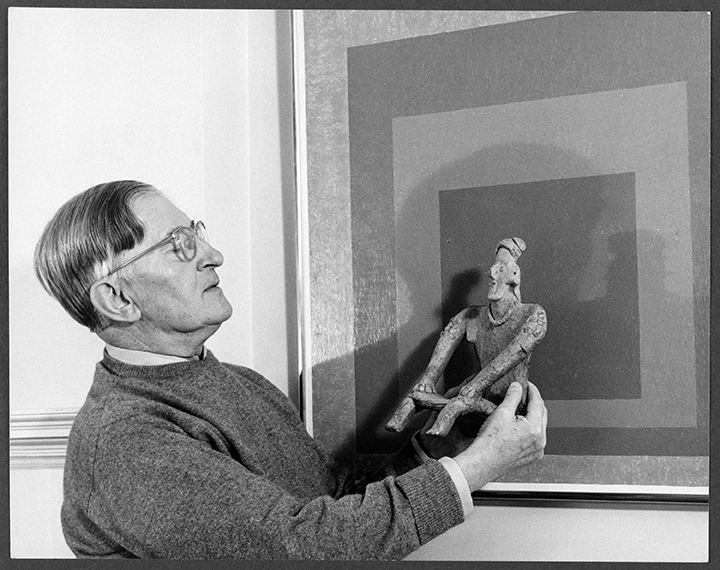

Fig. 10. Untitled (Josef Albers Holding a West Mexican Figure in front of his “Homage to the Square: Auriferous”), photograph by Lee Boltin, 1958. Gelatin silver print, 7 1/4 by 9 1/8 inches. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, © Lee Boltin; photograph courtesy the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

While Anni shared Josef’s kinship with pre-Hispanic figurative objects, she was particularly drawn to collecting and studying the textiles of modern and ancient American weavers. She learned how to use a traditional backstrap loom in 1939 while she was in Mexico, and though she found it “terribly tricky,” she purchased one to bring back to Black Mountain College because she “thought it would be interesting to show students this way of weaving.”1 In addition to this loom, she purchased almost a hundred textiles (see Fig. 15) as part of the Harriet Engelhardt Memorial Collection, a teaching collection that was assembled at Black Mountain College in honor of one of her former students. The Engelhardt Collection, now housed in the Yale University Art Gallery, consists of a variety of textiles, including modern Mexican serapes and ancient Andean fragments.

Fig. 9. Male figurine with hands on knees, West Mexico, 300 BC–AD 1300. Ceramic; height 10 7/8, width 9 5/8, depth

6 3/8 inches. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation; Nighswander photograph.

For Anni and Josef, the resonances between their art practice and these pre-Hispanic objects led them to reject the categorization of pre-Hispanic art as “primitive.” Furthermore, they felt the abstraction of the human body in ceramic sculpture and the sophisticated execution of geometric forms in textiles were on par with the achievements in twentiethcentury art. This modern sensibility extended into Josef’s perception of a seated West Mexican male figurine (Fig. 11), to whom he attributed tastes similar to his own, writting that the figure “love[d] abstract art and ladies.”2 Josef literally created a modern backdrop for the figure when, for a photograph (Fig. 10), he juxtaposed the seated figure with his painting Homage to the Square: Auriferous. Meanwhile, Anni collected, studied, and analyzed the weavings of her “great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru.”3 She was focused on purchasing textiles that testified to the array of complicated weaving techniques accomplished with rudimentary tools, with examples ranging from delicate open-weave lace to visually complex double-weave.

Fig. 10. Panel fragment, Andes, Chimú, AD 1000–1476. Cotton, 7 7/8 by 16 7/8 inches. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, © Josef and Anni Albers Foundation; Nighswander photograph.

Fig. 11. Seated female figurine, Mexico, Campeche, Jaina, ad 600–900. Ceramic; height 5 3/4, width 3 5/8 inches. Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

For the first time in more than forty years, the pre-Hispanic works that Anni and Josef collected exclusively are reunited with the photographs, sketches, and artworks that these objects inspired. For Anni and Josef, these ancient artists engaged with abstraction, materials, pattern, and color in sophisticated and unexpected ways. Though many of the items in their collection are diminutive in size, Anni refers to the pre-Hispanic figurines as “small-great objects”4 because their visual impact far outweighed their scale. This exhibition sheds new light on the Alberses as collectors of pre-Hispanic art, and highlights the impact of ancient American art on modern art as a whole.

Small-Great Object: Anni and Josef Albers in the Americas is on view at the Yale University Art Gallery from February 3 to June 18, 2017.

1 Anni Albers to Ted Dreier, August 21, 1939, Dreier Correspondence 406, Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut. 2 Josef Albers to Bobbie Dreier, July 24, 1936, Dreier Correspondence 183, ibid. 3 Anni Albers, On Weaving (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1965), n.p. 4 Anni Albers and Michael Coe, Pre-Columbian Mexican Miniatures: The Josef and Anni Albers Collection (Praeger, New York, 1970), n.p.

Fig. 12. Tapestry with human figures and bird designs, Andes, Chimú, AD 1000–1476. Cotton, 23 by 25 inches. Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

JENNIFER REYNOLDS-KAYE is the Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman-Joan Whitney Payson Senior Fellow in the Education Department at the Yale University Art Gallery.