For those who love, truly love, Old Masters painting, a new exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy, 1500–1800, is a rare treat. Artemisia herself is already well known to the museum-going public: in addition to being a painter of considerable stature, she has become a feminist icon, the subject of narrative films, documentaries, biographies, and even novels. Other artists in the show, among them Sofonisba Anguissola, Fede Galizia, and Elisabetta Sirani, are known mainly to experts in the field. But there is a third tier of painters, including Ginevra Cantofoli and Diana Scultori, who have eluded the attention of all but the most assiduous researchers. As a result, By Her Hand opens up to us a largely unimagined continent. Even if, it must be admitted, most of the work on view does not quite rise to the highest level, true lovers of the Old Masters, who love them because they are the Old Masters, will find the novelty of the present exhibition, no less than the quality of many of its objects, to be irresistible.

Fig. 3. Allegory of Faith (A Sibyl?) by Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), early to mid-1720s. Pastel on paper, 24 ½ by 20 inches. Private collection.

Of course, men created the overwhelming preponderance of Old Masters paintings. But no sooner has one assimilated that fact than one begins to find women painters in far greater abundance than one ever expected. Their arrival on the stage of art history coincided with the gradual dissolution of the guild system, which itself coincided with painting’s gradual evolution, starting in the latter half of the sixteenth century, from a servile art to something approaching a liberal art. Before then, a woman would have been no more likely to take up painting than to become a carpenter or a blacksmith.

Some of the women who responded to the call of art could richly support themselves through their work. Rosalba Carriera’s pastel portraits, among them her Allegory of Faith in the present show, were prized throughout Europe in the eighteenth century (Fig. 3). Artemisia, in purely financial terms, was the most successful of all her sorority: she traveled to England and France to complete highly remunerative commissions for royal and aristocratic patrons, a success rivaled by only the finest male artists of the day.

Fig. 6. Cleopatra by Ginevra Cantofoli (1618– 1672). Oil on canvas, 29 ¾ by 23 ½ inches. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Robert Simon Fine Art, New York.

Many of the women in the show, however, were something closer to Sunday painters, the daughters and spouses of men whose professional interests they shared to some degree. Virginia da Vezzo was the wife of Simon Vouet, the foremost French classical painter (after Poussin) of the first half of the seventeenth century. (His outstanding portrait of his wife is among the finest works in the present show [Fig. 5].) Maria Felice Tibaldi was the wife of Pierre Subleyras, a distinguished history painter; and Marianna Carlevarijs, the daughter of the eminent Venetian scene painter Luca Carlevarijs. Artemisia herself was the daughter of the great Roman master Orazio Gentileschi, who rivaled Caravaggio, and, on more than one occasion, surpassed him. Rare indeed was the Old Master, male or female, who did not come from a family of artists. An isolated example at the Wadsworth is Ginevra Cantofoli, born into wealth and represented by a half-length portrait of Cleopatra (Fig. 6). She studied with the distinguished, if short-lived, Elisabetta Sirani, whose darksome depiction of Portia Wounding her Thigh is also on view (see Fig. 7).

The Old Masters tradition by its very nature was conservative, in the sense that its members very rarely sought originality for its own sake: to the contrary, unless there was some compelling impulse to do otherwise, they studiously reenacted the thematic, formal and chromatic traditions in which they were raised. And so it should come as no surprise that the women at the Wadsworth were mostly content, in varying degrees of fealty and success, to reinforce the habits of their age and of the workshop in which they trained. Artemisia is more distinguished by the power and polish of her art than by any quest for novelty. Her fine Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (see Fig. 1) is based on contemporary works by Guido Reni, while her Lot and His Daughters, painted during a stay in Naples, reflects the influence (and perhaps even the contributions) of the local artists Mico Spadaro and Bernardo Cavallino. She comes closest to originality in Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes: the Biblical heroine, in a bright yellow gown, and her servant in bright blue, are sharply illuminated, in the finest Carravagesque tradition, by the light of a single candle (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9. Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy by Artemisia Gentileschi, 1620–1625. Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 by 41 3/8 inches. Private collection, on long-term loan to Venice Fondazione Musei Civici, Palazzo Ducale, Italy; photograph by Dominique Provost Art Photography, Bruges, Belgium.

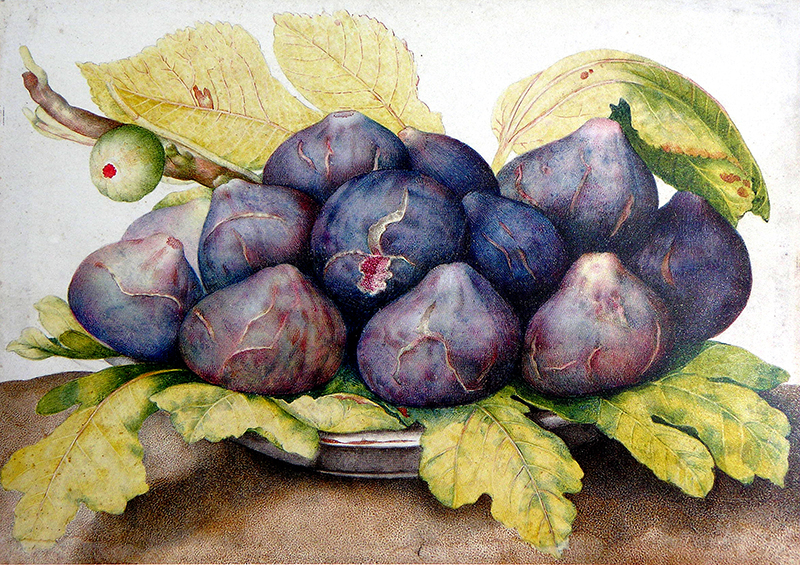

Two of the most energetically original artists in the present exhibition are the still-life painters Giovanna Garzoni and Fede Galizia, who was the author of the fine Glass Tazza with Peaches, Jasmine Flowers and Apples of about 1607 (Fig. 4). Garzoni, meanwhile, often worked in the highly unusual medium of tempera on parchment and is represented by three works at the Wadsworth. Her Still Life of Quinces, Almonds and Figs with a Mouse (c. 1632–1637) and her Plate of Figs (Fig. 10) combine intensely naturalistic observation with a curious flattening of the picture plane that is unparalleled in seventeenth-century art. Even more striking is her Hedgehog in a Landscape (c.1643–1651), a nearly monochromatic scene in which each spiky bristle of the creature is scrupulously recorded, together with a snail, acorns, and two chestnuts.

The struggle of women artists in ages past, both in Italy and elsewhere in Europe, has rightly been called an Obstacle Race by the feminist author Germaine Greer, per the title of her 1979 book. And yet honesty compels us to admit, as Greer often does not, that however important the achievement of these artists, for whatever reasons they did not rival, let alone surpass, the finest work of their male counterparts. Notwithstanding Artemisia’s gifts, her skill and originality did not equal her father’s or Caravaggio’s. Élisabeth Vigée Lebrun was likewise one of the finest portraitists of eighteenth-century France, but no one would seriously suggest that her portraits or those of any of her contemporaries, male or female, could rival those of Titian or Rembrandt or Velasquez. It would not be until the second half of the twentieth century that Western art produced women artists whose stature rivaled the best work of any male artist, living or dead. Each of us will assemble our own private pantheon. Mine, without the slightest hesitation, would include Agnes Martin, Alice Neel, Lee Bontecou, and Yayoi Kusama, and I am just getting started.

By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists of Italy, 1500–1800 is on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art to January 9, 2022