There was, as ever, a lot to see at this year’s Winter Show—the New York City art fair that serves as an annual reunion for the world of antiques. Front and center was an exhibition from the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, a little-known gem right here in Manhattan. Curated by former Metropolitan Museum of Art director Philippe de Montebello and interior designer extraordinaire Peter Marino (no less), the presentation included Old Master paintings, silver, ceramics, and vintage photographs. One work in particular leapt out to me: a map of the Ucayali River, which is located in the Amazonian headwaters in Peru. Made between 1808 and 1812 at the behest of Franciscan missionaries, it includes scenes of indigenous people hunting wild animals along the river’s sinuous banks. Though the map was apparently rendered with the assistance of native people, its portrayals of them are little more than cartoons.

A little further into the fair was the booth of Gemini Antiques, where I saw something else that stopped me in my tracks: a cast-iron head atop a tiny pair of shoulders, with popping eyes and ruby red lips fixed in a permanent grin. It was functional, with a little mechanical arm and hinged jaws. Put a coin in the hand, press the lever, and it will flip the coin back into the mouth. If you spend time around antiques, you’ve probably seen items like this one before, and you know what they’re called (hint: it’s unprintable). No getting around it, the object is a racist caricature. Gemini had a good many other similar artifacts too, though not all of them were equally objectionable: another of their mechanical banks bore the legend “Darktown Battery” and depicted a scene from pre-Negro League days, the athletes portrayed with no less admiration than on a period baseball card.

“Black Americana” has its own specialist collector base—some of whom are themselves African American. The Los Angeles collector Oran Z is one. He made headlines in 2018 when national media outlets covered his frustrated efforts to find a public museum to acquire his collection, which includes items both racist and celebratory: “anything and everything for blacks, against blacks, by blacks,” as he explained. “We got to preserve the whole story. And if you can’t see it, it don’t exist.” Ask most of those with an interest in such artifacts—including the folks at Gemini—and I’m sure they would agree. Taking these things out of circulation would be an act of amnesia, helping no one except those who want to forget the ugliest aspects of the American past.

But if it’s easy to make the case for preserving offensive historical artifacts, it is a lot harder to say what should actually be done with them, especially right now, when sensitivity about issues of representation is running high. Nor is this a minor problem of “political correctness.” Few decorative arts are as repellent as nineteenth-century caricatures of black people, but stereotypical imagery of Asians, Africans, and Native Americans can be found on everything from japanned cabinets and engraved silver to embroideries and delftware, and many of these objects are connected directly to histories of imperialism, enslavement, and genocide. Such artifacts are often presented in museums without comment; but it’s arguably only our contemporary sensitivities that make black Americana seem any more problematic.

Stereotype may be a blunt instrument, but this doesn’t mean that its operations should go unexamined. Indeed, they can be surprisingly complex. Consider the “Heathen Chinee” pitcher designed by Karl L. H. Mueller and made by the Union Porcelain Works—the creative team that also realized the celebrated Century Vase for the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. The pitcher, also shown at the centennial, was inspired by a poem by Bret Harte first published in 1870. Wildly popular at the time, it tells the tale of a frontiersman named Bill Nye, who has wagered on a card game with a Chinese immigrant called Ah Sin. (Though it is not explicitly stated, they are presumably both railroad workers.) The poem’s narrator sees that Nye is a cheat:

“And my feelings were shocked

At the state of Nye’s sleeve,

Which was stuffed full of aces and bowers,

And the same with intent to deceive.

At first, Ah Sin seems innocent—even of the game’s rules. But when he starts winning big, Nye realizes something is afoot. “Can this be?” he cries. “We are ruined by cheap Chinese labor!” Violence breaks out. And by the time it’s all over,

The floor it was strewed

Like the leaves on the strand

With the cards that Ah Sin had been hiding,

In the game “he did not understand.”

This scene is rendered on the pitcher in Chinese-inspired materials, unglazed porcelain in low relief against a light celadon ground. Cards with hand-painted pips fly. Nye has his knife out, and grips Ah Sin by the throat. As a metaphor for cross-cultural relations, it hits depressingly close to home: two dishonest brokers, each of whom thought they’d get the better of the other.

“The Heathen Chinee”—in both its poetic and ceramic forms—draws attention to the corrosive dynamic common to all caricature. It is the willful attempt not to understand, refusing other people their full measure of subjectivity—which is why it makes sense to turn them into objects in the first place. Ultimately, caricature is a failure of the imagination. The challenge to us, today, is to complete the stories it leaves untold.

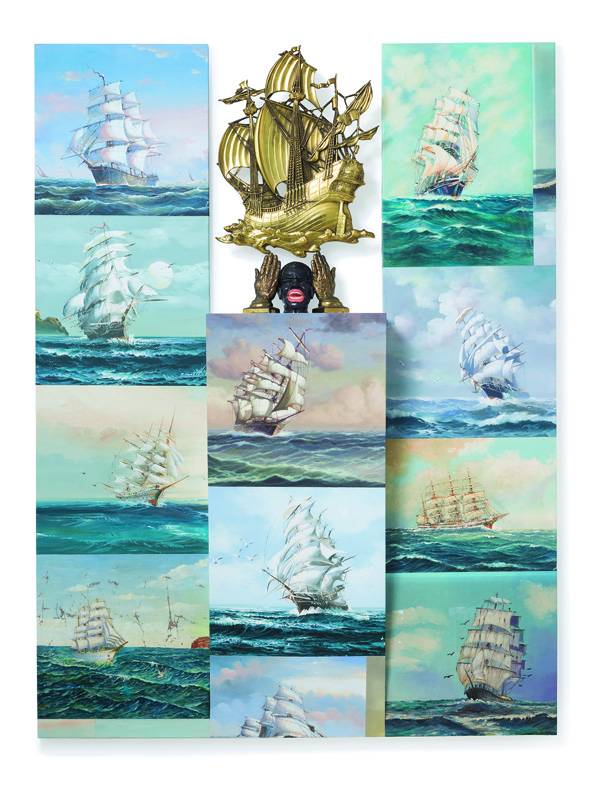

A powerful model can be found in the concluding segment from Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled (if you have YouTube on tap, take a look), in which sequences of live and animated blackface, mined from film history, are lined up one after another and set to a poignant soundtrack. The whole montage is only three minutes long, but it accumulates to heartbreaking effect. The contemporary artist Nick Cave achieves something similar in his series Made by Whites for Whites, in which examples of black Americana are incorporated as found objects. One of the most potent of these works, entitled Sea Sick, is centered on a blackamoor head, its eyes shut tight, hands spread to either side in a gesture of protection, or perhaps supplication. A golden galleon floats above, banners flying, while images of other ships careen on all sides. Of course we think of the slave trade, a horror too big to portray, yet Cave manages it. Like Spike Lee, he does so by taking stereotype’s malign power seriously, while also exposing its cramped inadequacies. This is how to deal with offensive caricature: not by averting our eyes, not even by confronting it head-on, but by setting it within the larger landscape in which real people live, think, and feel.

1 Dylan Thuras, “What a Lifetime of Collecting Millions of Relics of Black Americana Looks Like,” All Things Considered, npr.org, August 7, 2018. 2 See “Plain Language from Truthful James,” twain.lib.virginia.edu.