John Singer Sargent was an enigma, even to those who called him a friend. The premier painter of portraits on either side of the Atlantic, Sargent lived a very public expatriate life, but was hard to pin down—charming to women, drawn sexually to men, he practiced a discretion that let him prosper, even in London during Oscar Wilde’s trial for “gross indecency.” One close, longtime acquaintance called him a “completely accentless mongrel,”1 which seems apt for a Yankee who was born in Florence, Italy, first set foot on his native land at age twenty, and navigated the utterly different social and art scenes of late nineteenth-century Paris, London, and America with ease.

In his lifetime, Sargent was a phenomenon, a wizard with paint, a colossal success—and, for his contemporaries, an equally big target. Journalists knew his pictures made good copy. Jostling crowds—sometimes unfriendly crowds—turned out for his latest portraits at the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy. Henry James compared him favorably to Velasquez. Walter Sickert, the great British painter, filed him amid “the chiffon and wriggle school of portraiture.”2

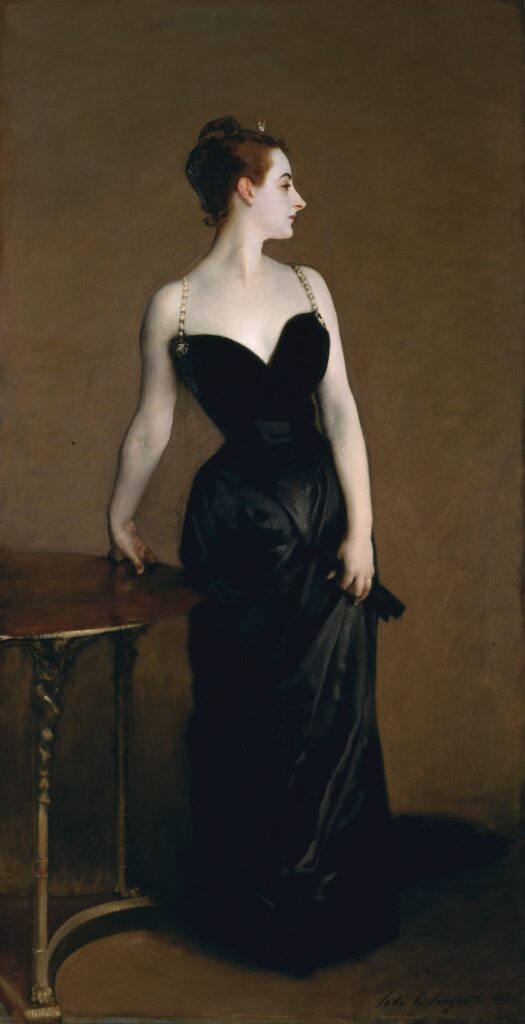

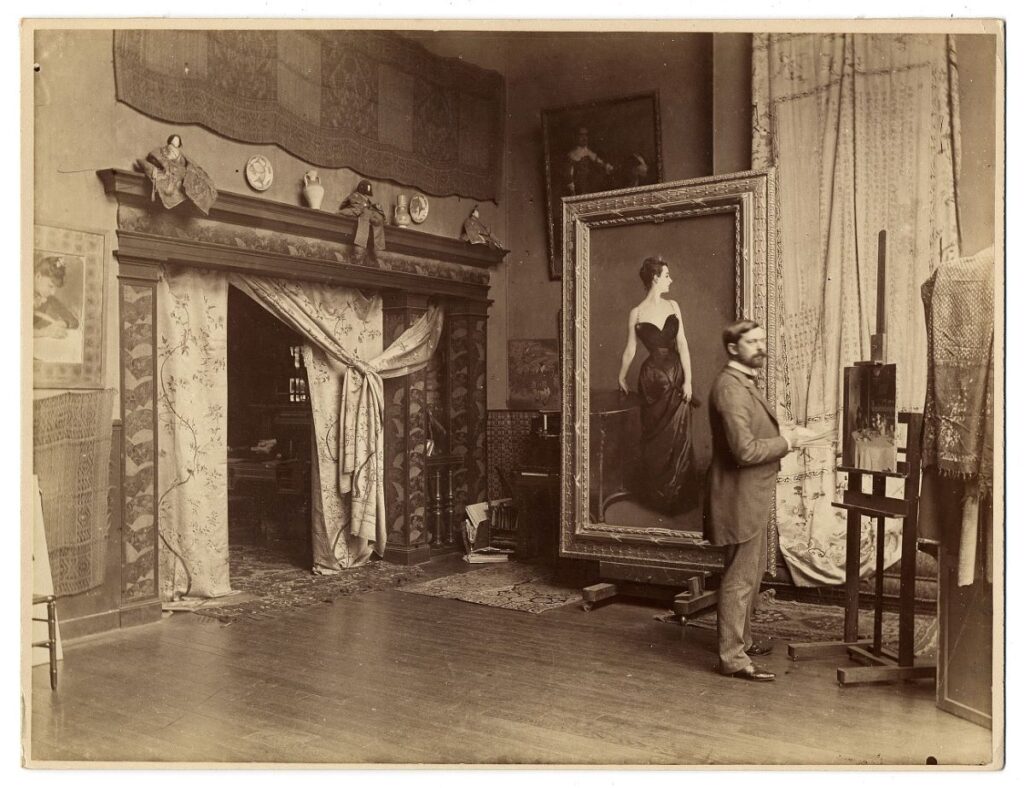

To judge for yourself, plan a visit to Fashioned by Sargent, an exhibition co-organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Tate Britain and opening in Boston in October. The exhibition gathers about fifty of the artist’s most celebrated canvases—from Madame X (Fig. 5), which scandalized viewers at the 1884 Paris Salon, to the sketch-like scenes such as Nonchaloir (Fig. 4), rendered in liquid calligraphy, that Sargent staged with his intimates in the years before World War I.

Sargent’s full range as a portraitist comes through in the Boston show, thanks to some notable loans. Look for La Carmencita, Sargent’s portrait of a sassy, hands-on-hips costumed performer, borrowed from the Musée d’Orsay (Fig. 2). That picture’s chromatic fireworks seem even more explosive when set beside the brooding full-length Lord Ribblesdale, which often hangs among Old Master paintings by Joshua Reynolds and Anthony Van Dyck in the center hall of London’s National Gallery (Fig. 7).

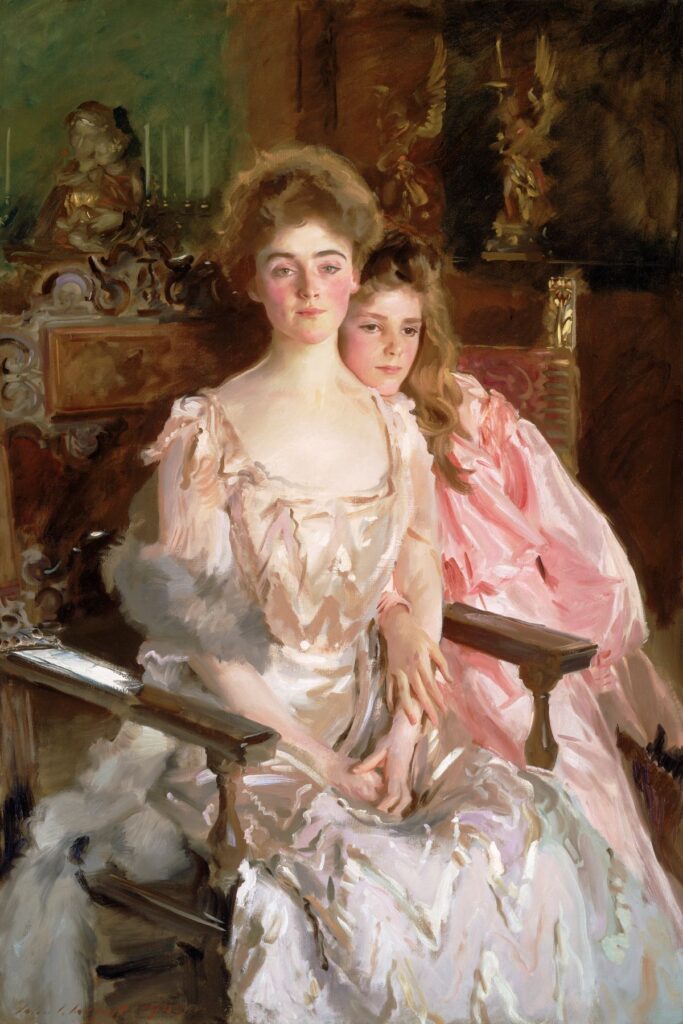

Key loans also come from smaller institutions: the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center shared its portrait of the cooly reserved adolescent sitter Elsie Palmer. Rarely seen works from private collections also add luster to the Boston exhibition. Among the best: Sargent’s 1907 portrait of Lady Sassoon, whose probing, intelligent gaze says everything about the agency of Sargent’s female sitters (Fig. 9).

Costuming and fashion always were a key element in Sargent’s studio practice and the new show emphasizes its importance both to the painter and his many high society clients, says Erica Hirshler, senior curator of American paintings at the MFA. She describes an artist who worked like a stage director, selecting garments for his subjects, sometimes customizing the pieces, and editing the results on canvas.

“When Sargent fell out of fashion among modern artists and mid-twentieth century collectors, he was viewed as a servant of his sitters, a fluid technician beholden to those who commissioned him,” Hirshler says. “But no one went to Sargent because they wanted every ribbon on their Worth gown recorded for posterity, they wanted to be recognized by the most celebrated painter of the day. They wanted to become Sargents.” She adds: “One needs to remember that these paintings weren’t just hidden away in private collections. They were meant to be displayed—and judged—in settings like the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy. That public exposure was as important for Sargent’s clients as it was for the painter himself.”

For this show, Hirshler and her team have tracked down many garments and accessories worn by Sargent’s sitters, and the side-by-side pairings are revelatory. Here one can see Lady Sassoon’s opera cloak (Fig. 8), and the red velvet dress worn in Sargent’s 1887 Mrs. Charles Inches. One can compare Sargent’s surging brushwork to the yellow silk, gilt thread, spangles and beads of the original, over-the-top costume worn in La Carmencita (Fig. 1).

These pairings usually show the painterly liberties taken by the artist, but they also underscore how much his style was suited to an era of opulence and public display. One of the exhibition’s most significant loans is the costume, encrusted with beetle wings, worn by actress Ellen Terry when she played Lady Macbeth (Fig. 13). It’s paired with Sargent’s 1889 portrait of Terry in the role (Fig. 14). The dress and the painting have not been seen together since Sargent and the actress were at work in the studio.

“Sargent’s sitters didn’t need encouragement to play dress up,” Hirshler says. “Their lives were full of pageants, costume balls, parades, and uniforms. Dress up was part of the program. They were on display at all times—and a portrait by Sargent was another way to show off. He turned them into avatars for public consumption.”

All of this has proved rich material for scholars. More than a dozen contributed to Hirshler’s exhibition catalogue—a jargon-free trove of facts and judgments that makes compelling reading even for non-specialists.

Scholars focused on women and fashion can look forward to the new Sargent exhibition in part because it spotlights the extravagant couture of the period—much of it crafted by women—and lets one think about the dynamic between Sargent and his sitters. “Commissioning a likeness was a social claim, whether you were a middle-class person with a twenty-cent tintype or a woman from the one percent who could turn to an established portrait painter,” says Elizabeth L. Block, an art historian and editor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and author of the recent book Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion (see excerpt in The Magazine ANTIQUES, January/February 2022). “The sitters wanted something that wasn’t too trendy, that would last a lifetime—an image that could be passed down through generations. We know that from reading the journals and letters of sitters, and from reading newspaper accounts. Sargent’s talent wasn’t just as a painter—to treat him that way isn’t useful for art historians. He was a psychologist, a listener, and a genius of adaptation. He and his sitters knew that every portrait is a collaboration.”

Sargent must have understood the pitfalls of this arrangement—at least to judge from his wry definition of the work he produced for hire: “A portrait is a painting with a little something wrong about the mouth.”3 For all his success, he grew tired of portraiture as his career unfolded. In the decade before the First World War, for example, Sargent made multiple trips to Italy, spending months at a time painting Vatican monuments, Sicilian landscapes, and hundreds of views of Venice—much of the work done in the uncommercial medium of watercolor.

Still, one thing never changed about Sargent. He made luxury objects for his clients, and, for himself, he reserved the greatest luxury of all: artistic freedom. Call him a genius of collaboration, or call him a genius with the brush—it hardly matters. The evidence is in the Boston exhibition.

In work after work, Sargent unites painterly virtuosity with authentic emotional engagement, separating himself and his portraits from the obsequious renderings of conventional society painters. Here the details often speak for the whole. Just look at the broad, pigment-laden swipes that resolve into a lavender sash in his iconic 1892 portrait, Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (Fig. 11). That painted passage does yeoman service by defining the subject’s waist, and it also charges the composition, offering a colorful fabric counterbalance to the undulant forward thrust of his sitter’s silk-robed thighs. But Lady Agnew’s painted sash, spilling out of the frame, is also a living thing, a liquid, flowing force that conjures both the inner vitality of the sitter and Sargent’s boldness of touch. With those few decisive brushstrokes, Sargent sends viewers back to the moment of creation, back to the hours when he faced his client in the quiet of the studio, back when he made her immortal.

“For those who love painting, Sargent delivers every conceivable pleasure,” Hirshler says. “His portraits aren’t just images that one can consider in reproduction. And they are much more than documents of Gilded Age social relations. They are 3-D objects, layers of paint on canvas, bravura performances that need to be experienced in person to really understand their expressive power. He made some of the most seductive paintings in Western Art. They are sensual in the extreme. They breathe.”

Fashioned by Sargent will be on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from October 8 to January 15, 2024, and at Tate Britain from February 22 to July 7, 2024.

1 Richard Ormond, “John Singer Sargent and Vernon Lee,” Colby Library Quarterly, ser. 9, no. 3 (September 1970), p. 12, quoting Vernon Lee’s Letters,ed. Irene Cooper Willis (Privately printed, 1937), p. 61. 2 Fashioned by Sargent, ed. Erica E. Hirshler (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2023), p. 29, quoting Walter Sickert, Complete Writings on Art, ed. Anna Gruetzner Robin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 243. 3 Sargent to Edwin Austin Abbey, undated, in Fashioned by Sargent, p. 21, quoting Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Scribner’s, 1927), p. 137.

CHRIS WADDINGTON, a frequent contributor to The Magazine ANTIQUES, is an arts and culture writer based in New Orleans.