When the news came out this past March, historians everywhere sat up a little straighter: Joe Biden had invited a group of their own to the White House. Among them were Doris Kearns Goodwin, Michael Beschloss, and Walter Isaacson, a who’s who of experts on the American presidency. The principal topic of the two-hour conversation was Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his implementation of the New Deal. Journalists, unable to resist the comparison, pointed out that Donald Trump had gathered a summit at the same point in his own administration, consisting of Sarah Palin, Ted Nugent, and Kid Rock. But there was also some scoffing about Biden’s own intentions. Only in office for a few weeks, was he already anointing himself as the second coming of FDR?

I had a different problem. While certainly pleased that scholars were being consulted, I really wished Biden had invited an art historian. If he had, he might have heard a powerful argument about the role of culture in national recovery. To be sure, that hadn’t been Roosevelt’s first priority either. During his famous first hundred days, as he aimed to heal “a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world” (sound familiar?), he rammed a huge slate of legislation through Congress. Among the signal achievements was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which brought hydroelectricity to millions, and the Public Works Administration, which constructed bridges, airports, public housing, and the Lincoln Tunnel. But it wasn’t until 1935, as part of the so-called “Second New Deal,” that the culture sector began receiving funding at a mass scale, through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which included provision for writers, musicians, theaters, and the visual arts.

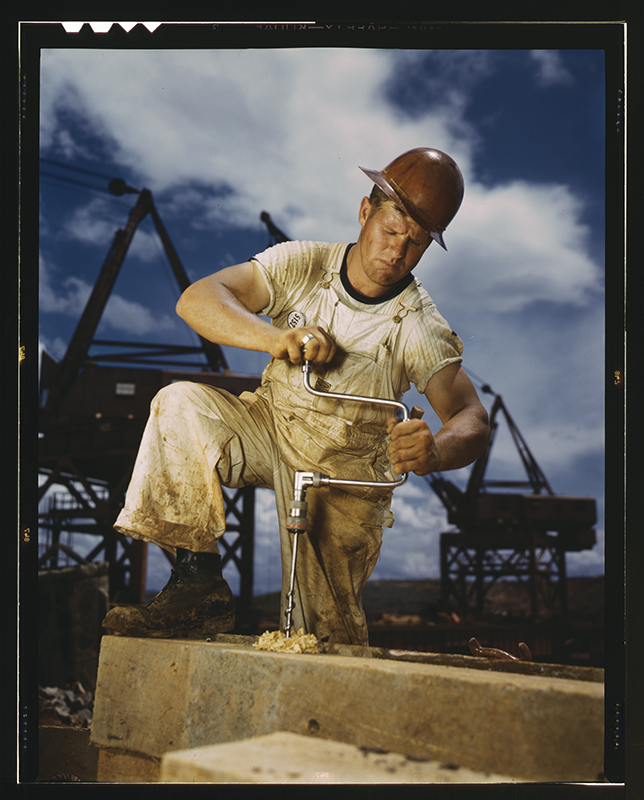

Through the WPA’s subsidiary, the Federal Art Project, murals were painted for schools, libraries, and post offices. Public sculpture was erected in cities and towns. Photographers like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Alfred Palmer fanned out across rural America, documenting the trials and tribulations of the Depression era, and capturing indelible images of construction projects such as the TVA. Figures associated with the Harlem Renaissance received support, too, among them Aaron Douglas, the sculptor Augusta Savage, and Jacob Lawrence, who got his start thanks to WPA programs.

The national director of the Federal Art Project was a fascinating man called Holger Cahill. Born in Iceland— his birth name was Sveinn Kristjan Bjarnarson—he was a wholly self-invented character. After bouncing around as a manual laborer in his teens and twenties, he arrived in New York in 1913, during the flourishing years of the Ashcan school. He managed to establish himself as an art critic, eventually organizing exhibitions at the Newark Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. Once appointed head of the FAP, his leadership was startlingly prescient, embracing artistic diversity to a degree then unprecedented, and arguably not matched for decades afterwards. This was diversity in all senses. The Federal Art Project was remarkably progressive for its time in terms of ethnicity, gender, genre, and region, for as art historian Jody Patterson has noted, “It brought exhibitions, educational centers, and art lessons across regions that had not been well-served, and into communities that had very much been disenfranchised from culture.”

A 1936 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art called New Horizons in American Art, highlighting the FAP’s early achievements, showcased Cahill’s boldly non-hierarchical vision. Easel paintings and sculpture sat alongside vernacular crafts and even children’s artwork. One star of the show was Patrociño Barela, an itinerant agricultural worker whose santos (carvings of saints) were received in the press as the equal of works by Brancusi, Modigliani, and Picasso. It would be interesting to know if Cahill saw something of his own picaresque biography reflected in Barela’s; in any case, his barnstorming essay for the exhibition catalogue made a strong case for public funding of the arts as a pillar of democracy: “There is a theory that art always somehow takes care of itself, as if it were a rootless plant feeding upon itself in sequestered places… [that] no matter what happens, a few artists starving in garrets will see to it that art does not die. It is quite obvious that this theory will not hold.”

Not all of Cahill’s initiatives were prescient, of course. Take, for example, the Index of American Design, an astounding compendium of more than eighteen thousand watercolor paintings depicting decorative arts and material culture, rendered in gorgeous detail. Conceived partly by leading modern and folk art dealer Edith Halpert (subject of a recent show at the Jewish Museum in New York), the Index was intended as a quarry for inspiration—a “usable past” that might serve as a foundation for future progress. This quintessential colonial revival project did provide employment to hundreds of out-of-work commercial illustrators, and preserves a fascinating cross-section of period taste. But usable? Not so much. The images were almost immediately superseded by color photography. Now stewarded by the National Gallery of Art (and available online), they are very beautiful to look at, but poignant in their pointlessness.

In most of its activities, though, the Federal Art Project paid dividends that we are still reaping today. Its greatest impact was not through centrally directed projects like the Index of American Design, or the many civic murals that it commissioned, but simply in supporting so many creative livelihoods. Many key artists of the postwar generation—Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Louise Nevelson, and Arshile Gorky among them—were sustained by federal funding in the 1930s. These snarling young bohemians were certainly not who Cahill imagined as the standard-bearers of American art. But they actually did go on to discover its “new horizons.” It is quite possible that without FAP patronage, abstract expressionism would never have taken root. Art history would have been immeasurably poorer, and so, too, would the nation, which—once recovering from the shock of the new art—came around to seeing it as a clarion symbol of American freedom. By the 1950s, the US Government was assiduously promoting abstract expressionism at home and abroad.

The lesson here is that official and unofficial culture nurture each other in unpredictable ways. Like every government program, the Federal Art Project had its inefficiencies and blind spots. No matter how you look at it, though—art historically, or even just as a return on capital investment—the cultural programs of the New Deal era were a stunning long-term success. Unfortunately, they are also an isolated phenomenon in our national history. The Federal Art Project ended in 1943. Its successor, the National Endowment for the Arts (formed in 1965 during the Lyndon Johnson presidency) has never had comparable impact, and has been beset by partisan infighting since the culture wars of the 1980s. In 2020 it distributed $77.5 million in awards. That may sound like a lot of money, but it is only about one-third of the annual budget of a single big city museum.

At the time of this writing, an ambitious infrastructure bill—the Biden proposal that most closely mirrored Roosevelt’s recovery strategy—was just being taken up by Congress. Here and there, calls came forward for a parallel investment in culture. Perhaps there should be a new cabinet secretary position: “an Anthony Fauci for the arts,” as an editorial in the Washington Post put it, though they might more accurately have said a twenty-first-century Holger Cahill. Such decisive moves won’t be happening this year, presumably. By 2023, who knows? It is axiomatic that those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it. Equally true, though less often mentioned, is that amnesiac societies fail to revisit their own best ideas. It’s time for the government to sit back down at the table of culture, and deal itself in.