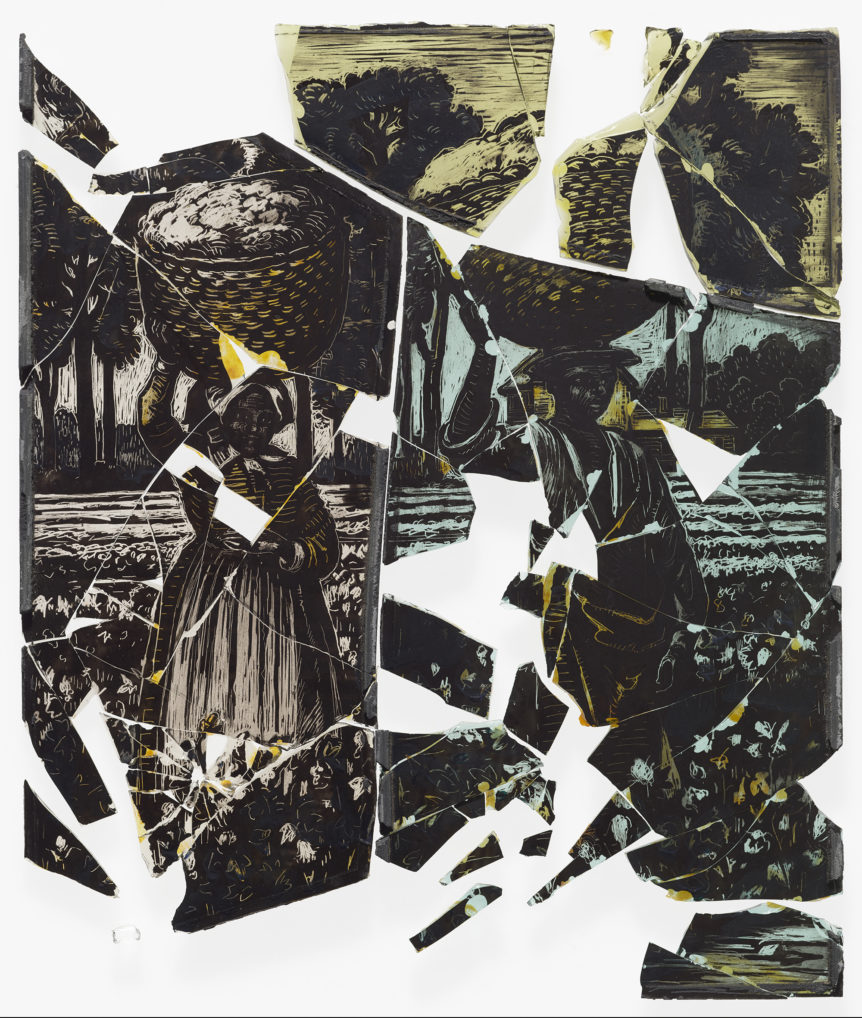

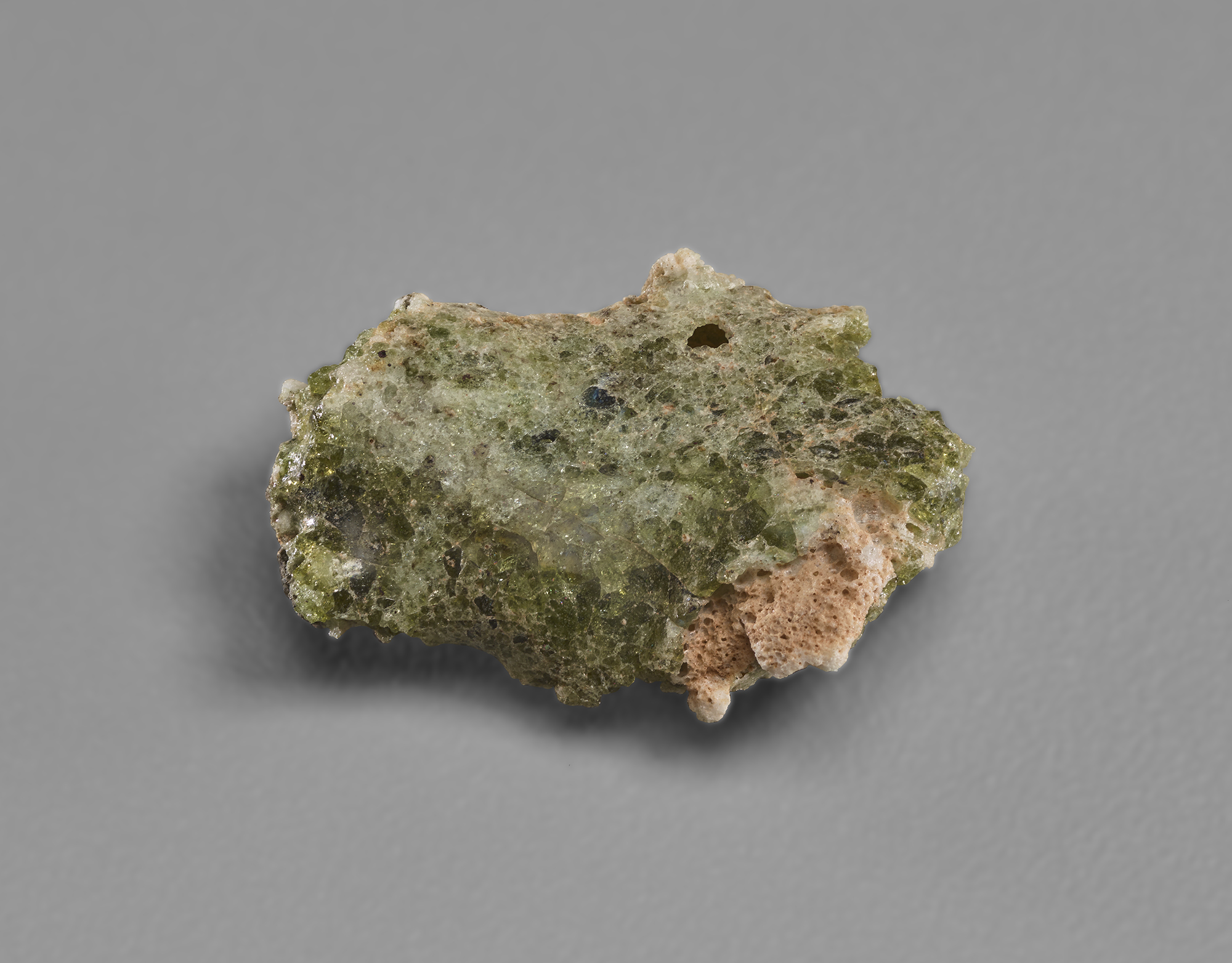

Right: Trinitite from Socorro County, New Mexico. 7/8 by 1 ¼ by 3/8 inches. Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, Connecticut. Left: Cotton Field (broken) by D’Ascenzo Studios, Philadelphia, 1932. Vitreous enamel on plate glass, 12 by 9 ¼ inches. Yale University.

In this episode of Curious Objects, host Ben Miller pays a visit to his alma mater to speak with John Stuart Gordon, associate curator at the Yale University Art Gallery. In 2018, Gordon published American Glass: The Collections at Yale (recently featured in our pages), and the pair take a closer look at two of the objects featured in the book: a piece of trinitite—glass formed in the 1945 Trinity nuclear test—and a stained-glass window formerly installed in Yale’s Hopper College and broken in 2016 by a dining hall worker. Gordon calls upon the expertise of mineralogist Stefan Nicolescu and historian David Blight during this deep dive into the tortured history of glass at Yale.

John Stuart Gordon: Glass is a remarkable material. It can be transparent, it can be sharp, it can be luminous, it can be non-conductive, it can be radioactive, it can be broken, it can be mended. It has a lot of possibilities,

Benjamin Miller: Hello! You’re listening to Curious Objects, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m Ben Miller. I have two objects to share with you today, and three guests. Our guide, whose voice you’ve just heard, is John Stuart Gordon, associate curator at the Yale Art Gallery and author most recently of American Glass: The Collections at Yale. I’ve known John for years and am thrilled to have him on the show—he’s one of the great exponents of a new generation of curators.

John and I will be joined first by Stefan Nicolescu, collections manager in the Division of Mineralogy and Meteoritics (wow!) at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Later on, we’ll talk with David Blight, professor of American History, also at Yale.

Our two curious objects today are both featured in John’s book. We chose these particular pieces because they both, in very different ways, carry the weight of history. One is the by-product of the most destructive forces known to humankind. The other is a haunting memento of America’s racial past, and also a stark symbol of our present struggles. We have a lot of ground to cover, so let’s get started.

First, a word from our sponsor.

Are you ever curious about why blue diamonds are so alluring, or have you wondered about two hundred years of legal history in Philadelphia? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, tells the stories of these and other curious objects. Discover Pennsylvania’s craft legacy, go behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, and uncover your passion for collecting. Visit www.freemansauction.com to sign up for their newsletter, and get these stories and more delivered straight to your inbox.

Trinitite from Socorro County, New Mexico. 7/8 by 1 ¼ by 3/8 inches. Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, Connecticut.

Benjamin Miller: So let’s just dive straight into talking about this very curious object, which . . . you tell me: Should I be nervous sitting as close to it as I am?

Stefan Nicolescu: Not in the least.

Benjamin Miller: And why is that? Because it does come from a radioactive event.

Stefan Nicolescu: Yes. And it is still very, very mildly radioactive. But nothing that can affect anybody’s health.

Benjamin Miller: Ok, so I won’t see my bones if I hold it in my hand?

“It was formed shortly after 5:29 AM on July 16, 1945, when the first nuclear explosion happened south of Los Alamos in New Mexico.”

Stefan Nicolescu: No definitely not.

Benjamin Miller: Ok. Now tell me what is this object that we’re looking at.

Stefan Nicolescu: So this is basically molten rock. It was formed shortly after 5:29 AM on July 16, 1945, when the first nuclear explosion happened south of Los Alamos in New Mexico. So this was the first test of an atomic bomb. And the material in the specimen that we have here, which is about three centimeters across, was actually the result of the high temperature generated—extremely high temperature generated—by the explosion. The temperature in the cloud . . . it’s estimated to have reached almost 15,000 degrees Fahrenheit. So, what happened is that the material on the ground under the tower in which the explosion took place was kicked up into the cloud—the nuclear cloud—at that high temperature. The material basically again got vaporized, but then it cooled down somewhat and it rained down as melt on the ground and it transformed itself into a glass.

“Glass is a solid that can be formed either by natural processes or by artificial processes. And the main characteristic that distinguishes it from other naturally-formed solids is that it doesn’t have crystal ordering.”

Benjamin Miller: Ok. Let’s back up here for a second because we’re talking throughout this episode about glass, but we haven’t yet really defined what glass is. So, there are a lot of different kinds of glass and glass is formed in different ways. So, tell me, What are the broad categories of types of glass?

Stefan Nicolescu: So glass is a solid that can be formed either by natural processes or by artificial processes. And the main characteristic that distinguishes it from other naturally-formed solids is that it doesn’t have crystal ordering. There is no crystal structure. It’s an amorphous material.

Benjamin Miller: And so when people say that glass is a liquid is that what they mean?

“When you’re looking at an old stained-glass window and you see the ripples and you see the weight at the bottom edge of a piece, it’s not the fact that it’s been sagging over the past hundred thousand years, that’s imperfections to how it was made.”

Stefan Nicolescu: You know, I didn’t live long enough to see it indeed flowing. It’s called a very high-viscosity fluid—

Benjamin Miller: So when you look at old glass—stained glass windows from Gothic cathedrals, for example—and you see a little bit of rippling in the surface, Is that a result of that sort of liquid property of the material?

John Stuart Gordon: No, that unfortunately is a myth. People have taken the idea that glass is an amorphous solid and kind of extrapolated out to the fact that the old glass has imperfections. So, when you’re looking at an old stained-glass window and you see the ripples and you see the weight at the bottom edge of a piece, it’s not the fact that it’s been sagging over the past hundred thousand years, that’s imperfections to how it was made. What’s going to sag faster is the lead holding the glass. So, if you see it moving and buckling it’s actually the lead frames so

Benjamin Miller: That’s funny. I like that you’re debunking urban myths already.

John Stuart Gordon: That’s what we do here. You know, I love the idea that glass is a liquid and solid and that’s kind of what captures people’s imagination about it: the fact that you can see it in these two these two states within a matter of minutes. But you rarely see it changing on its own, spontaneously.

Benjamin Miller: Right.

John Stuart Gordon: It needs some kind of action to move it from one state to the other.

Benjamin Miller: Now, Stefan, you described this as . . . well, you described glass as being either natural or artificial. This particular piece falls somewhere in between those two categories.

Stefan Nicolescu: No, I think it falls right into the artificial—

Benjamin Miller: Right into the artificial.

Stefan Nicolescu: —because it wouldn’t have happened without human intervention.

Benjamin Miller: Is there any natural glass that shares properties with this piece?

Stefan Nicolescu: Well, not in terms of radioactivity, but in terms of composition and in terms of lack of crystallinity. So, for instance, when lightning strikes the ground that’s what happens. So, it’s really . . . I think lightning strikes are in thousands of degrees Fahrenheit or Celsius temperature and the sand quartz melts around seventeen hundred degrees Celsius. So that’s what you get. The rock is called fulgurite. And that is naturally-formed glass and there are other processes that generate natural glass.

“The minute the reporters who were there covering the story were let out into the crater people were scooping up this material as a souvenir.”

Benjamin Miller: Now how did this particular sample end up at Yale?

Stefan Nicolescu: It was purchased from a mineral dealer many decades ago when it was still legal.

John Stuart Gordon: Yeah, the material got out very fast. I mean, the reporters who were there covering the story . . . the minute they were let out into the crater people were scooping up this material as a souvenir. Life magazine and other periodicals were running specials about what to do with this new material.

Benjamin Miller: So, there was quite a lot of it?

John Stuart Gordon: There was a fair amount of it. I found an ad for nuclear jewelry. People were taking pieces of trinitite and setting them as precious stones in broaches and earings so you could actually wear this radioactive material as a symbol of the progress of the country.

“This is manmade glass. It’s manmade but it’s mimicking how a tektite or fulgurite is made and it’s tied to such an incredible story of the twentieth century: our quest for nuclear power, the destructive force of this science, the realities of war.”

Benjamin Miller: Right. John, give me a little bit more context here. We’re talking about a piece . . . your book has a hundred and fifty–something objects in it, and for the most part we’re talking about crafted glass, glass that was made for functional purposes or decorative purposes or artistic purposes. This piece was made almost by accident. The reason the nuclear bomb was detonated was not to produce glass, right, it was to produce a destructive and lethal force. Why did you feel that it was important to include this piece in your book?

John Stuart Gordon: I got captivated by the story because here was something that . . . as Stefan says, this is manmade glass. But it does kind of toe the line because it’s manmade but it’s mimicking how a tektite or fulgurite is made and . . . it’s pushing the envelope and it’s tied to such an incredible story of the twentieth century: our quest for nuclear power, the destructive force of this science, the realities of war. And the war changed how we live. So, to get an object that goes right to that one moment when man was able to harness the atom for something so powerful, destructive, and potentially positive—that was really compelling.

Benjamin Miller: You mentioned collectors being enamored of the idea of their pieces of jewelry made from trinitite tying them, in a sense, to technological progress, to the future of humanity. Was there also a sense among any of these people that what they were collecting and fashioning into jewelry and other things and wearing was also representative of terrible human destruction and, as you say, now, the cost of war?

John Stuart Gordon: Certainly. The anti-nuclear protests and people who are rallying against nuclear arms—that starts in 1945 and even earlier. It’s fully . . . that idea of protesting nuclear proliferation is just as old as the atomic tests.

“A lot of the objects that end up in museum collections or in private collections that celebrate the atomic world are rather positive, like George Nelson’s atomic clock or Eva Zeisel’s Fantasy pattern. This, by contrast, is an uncomfortable object.”

Benjamin Miller: Certainly, present at Los Alamos and among the scientists who were working on developing the technology?

John Stuart Gordon: Oh, yes. And you get a lot of a sense of ambivalence about “is this good/is this bad?” Even biographies of Oppenheimer kind of dwell on the fact that he was conflicted about what he was doing. So, although there is this sense of potential of the nuclear blast, there is this lethal side, and in many ways a lot of the objects that end up in museum collections or in private collections that celebrate the atomic world are rather positive, like George Nelson’s atomic clock or Eva Zeisel’s Fantasy pattern, or you can even think about Pyrex and Peter Schlumbohm’s Chemex comes out of thinking about science during wartime. These are rather positive aspirational objects. So I kind of like the fact that this is an uncomfortable object. It’s a fragment, it’s a shard, it’s just, by coincidence, it’s this bizarre color green that we do associate with radioactivity. Imagine a low-budget sci-fi movie where someone is radioactive and they’re glowing green. That’s not why this rock is green, but it’s a wonderful happenstance that it is.

Benjamin Miller: You mentioned Oppenheimer and the name of the material, trinitite, is derived from something that Oppenheimer said, isn’t it? Or, I should say, something that John Donne said that Oppenheimer was aware of and quoted.

John Stuart Gordon: Yes, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” Oppenheimer was incredibly well-read and the idea of salvation and redemption and destruction all coming together that John Donne talks about in that sonnet, Oppenheimer knowingly draws on when he names that test the Trinity test. This piece of glass has had many different names. Right when it was created . . . there was a whole series of names and I think trinitite is the one that has lasted through time. And I like it because of those poetic ramifications.

Benjamin Miller: Thanks to Stefan Nicolescu. We’ll take a quick break before John Stuart Gordon and I join David Blight to talk about today’s second object.

Do you want to learn how much was paid for the most expensive American looking glass ever sold at auction? I know I do. Or what an article titled “Puppies, Penguins, and Plagiarism” could possibly be about? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, has the answers. Discover how Thomas Eakins’s Gross Clinic Stayed in Philadelphia; delve into the work of Wayne Thiebaud, the great draftsman; and much more on their website freemansauction.com. From modern masters to French furniture, Freeman’s takes you behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, delivering the latest in art market news, events, and stories. Subscribe to their bi-weekly magazine, and get it sent straight to your inbox. Visit Freeman’s at www.freemansauction.com to learn more.

I like to take a moment each episode to thank you for listening. Your responses and comments are really helpful and encouraging, so do get in touch. You can email me at podcast@themagazineantiques.com, or catch me on Instagram @objectiveinterest. I post photos there about the podcast, including some behind-the-scenes shots. And you can always see relevant pictures at themagazineantiques.com. You’ll definitely want to see pictures of this next object if you can.

The other thing you can do that really helps me out is to leave a rating and a review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening right now. Every time one of you does that, it helps more people find this podcast, so many, many thanks to those of you who have done that.

Coming up in the next segment, our object is a stained-glass panel with a troubled political history. It was installed at Yale in the 1930s as part of a tribute to the legacy of a controversial figure, John C. Calhoun. The reason you may have heard of it is that in 2016, a Yale dining hall worker named Corey Menafee destroyed the panel in an act of protest, sparking a national debate about the vestiges of slavery in objects we see every day.

John Stuart Gordon included the panel in his book, American Glass, but asked professor David Blight to help him understand the historical context around it. I spoke with both of them at the Yale Art Gallery.

Cotton Field (broken) by D’Ascenzo Studios, Philadelphia, 1932. Vitreous enamel on plate glass, 12 by 9 ¼ inches. Yale University.

Benjamin Miller: John, can you tell us what we’re looking at? This is a panel of stained glass. It’s about nine by twelve inches, give or take, broken into fragments.

John Stuart Gordon: Yes, this is a window that was originally installed in the dining room of Calhoun College in 1932.

Benjamin Miller: And, just for clarification, that’s one of the residential colleges within Yale?

“This is a window that was originally installed in the dining room of Calhoun College in 1932.”

John Stuart Gordon: Correct. In the early ’30s Yale went through a period of rapid expansion. They erected a new library, a hall of graduate studies, a gym, and a series of residential colleges each named after notable people in Yale’s past, either administrators or notable graduates. And John C. Calhoun, at that point, was the Yale graduate who probably reached the highest level of American government when he was vice president. So he was deemed an appropriate figure to be memorialized. So they named this one Calhoun, and there was a decorative program conceived to decorate the college. Like most of these buildings they’re Gothic revival. They have faux medieval stained glass in them, but often the stained glass references some aspect of college life or life of the mind. And there is a staircase in Calhoun College that is decorated with prints of . . . by Currier and Ives. Sporting scenes. And the one wall of the dining hall was these kind of nostalgic views of the Old South, kind of a [salute] to Calhoun and the world he inhabited. And, I will say, I am using the term Calhoun College . . . it has since been renamed Hopper College—

Benjamin Miller: After Grace Hopper.

“One wall of the dining hall was these kind of nostalgic views of the Old South, a salute to Calhoun and the world he inhabited.”

John Stuart Gordon: After Grace Hopper, the navy rear admiral, right. I’m just using the historical term just because this window is installed in a building of one name.

Benjamin Miller: Right. So, David, who was John C. Calhoun and why was he such a bad guy?

David Blight: Or important guy, too. John C. Calhoun was a major American statesman from South Carolina, a planter, but one who came north for his education. He was educated at Yale early in the nineteenth century, read law in Connecticut—became a lawyer. He became a US senator, he became secretary of state, he became vice president. Calhoun, early, in his South Carolina career, was known as a nationalist. But with time, particularly after the great tariff crisis of 1829/30, Calhoun became more and more of a sectionalist, a states’ rights advocate, a staunch philosophical believer in the theory of state sovereignty over federal power but also a staunch supporter of slavery. He isn’t the name of the most important proslavery writer or advocate. There were others who wrote much more on that subject, but because of his political prominence what he did write in defense of slavery took on greater and greater significance in his own time and then over time as well.

“John C. Calhoun was a major American statesman from South Carolina. He isn’t the most important proslavery writer or advocate, but because of his political prominence what he did write in defense of slavery took on greater and greater significance.”

Benjamin Miller: And segregation and race relations and so on—those were secondary to this political theory?

David Blight: Secondary. Well, as issues in Calhoun’s legacy they were secondary for so long because of his writings about the Constitution, about federalism, and about political theory. That is not where our culture is at now. When this blew up in controversy, which led to the broken window, to suggest, as I actually did . . . and I wasn’t defending Calhoun. It was when the question of Calhoun College’s name came up I did a tea or a talk at the college the very first autumn that it was brought up and I just made the argument that, yes, Calhoun was a defender of slavery and a terrible defender of slavery but before we forget about him we may want to know why he was so important, historically. So important that a Frederick Douglass, the great black leader about whom I’ve written probably too much about . . . Douglass used to refer to the South as “Calhoundom.” He called it that. He would even mimic, sometimes, Calhoun by name in speeches when he wanted to mimic the ravings of a pro-slavery advocate. So that’s how important Calhoun was to abolitionists that they would even label the South by his name. And I remember suggesting to the students who came that day that, “you know, you might want to know some of this before you take it . . . take his name off this college. Just know how and why it ever got here.” But it just was not a moment in which that mattered very much. Because we live . . . we’re living in a racial reckoning, an extended racial reckoning again in America, especially after the massacre in Charleston, which led directly to President Salovey bringing this question up, such that by a year or so into this controversy the idea of keeping Calhoun’s name on the college became pretty much politically—

“Frederick Douglass, the great black leader, used to refer to the South as ‘Calhoundom.”

Benjamin Miller: Toxic.

David Blight: —unviable.

Benjamin Miller: Well, but let’s rewind back to the 1930s and I want to talk about nostalgia because this scene depicted on this glass is a sort of bucolic idea of what slavery might have looked like. And it’s it’s two slaves working in a cotton field. As you suggested earlier, they seem to be in a kind of a quaint, calm disposition. They seem to be comfortable, they seem . . . there is no visible sign of struggle or of pain or of . . .

John Stuart Gordon: Their clothes are not torn, they actually seem quite well-kempt. The landscape is quite serene, orderly.

“This was the image of the idyllic, noble, patriarchal South, of the “cotton kingdom,” a civilization that, yes, requires slavery, but it was essentially seen as benign.”

Benjamin Miller: Now, I think that today it would be hard to find someone who wouldn’t say that’s a gross misrepresentation, at least of anything that we know about the condition of slavery in the antebellum South. Where did this idea come? How . . . how would this scene have come to be portrayed in this way in the 1930s?

David Blight: Well, it had been portrayed this way hundreds and hundreds of times in lithographs, paintings for sixty years by then. This was the image of the idyllic, noble, patriarchal South, of the “cotton kingdom.” And they’re surrounded by cotton here. These are cotton fields of bolls cotton all around them. They’re both holding baskets of cotton on their heads African-style. A civilization that, yes, requires slavery, but it was essentially seen as benign, as somehow necessary for a people destined for labor and perhaps even destined to be beyond slavery and beyond labor, but this was seen as a stage of history that they and the country had to somehow live through.

Benjamin Miller: Now, I think of that as a Southern myth. And I grew up in the South in a place where there are plenty of people who still hold those—

“This is a window that was made for a building in New Haven, Connecticut, by a firm in Pennsylvania.”

David Blight: Where in the South?

Benjamin Miller: Tennessee. But this is a window that was made for a building in New Haven, Connecticut, by a firm in Pennsylvania, if I’m remembering . . .

John Stuart Gordon: Philadelphia, commissioned by a New York architect. Its a Northern story. But it does show how far the Lost Cause ideology pervaded and I remember talking to someone—

“The Lost Cause came into existence as a sort of cultural response to defeat. And part of that story—only one part of it—became that they never really fought for slavery. It was an effort to try to portray the Confederacy and the effort of the Confederacy as noble.”

Benjamin Miller: I’m sorry, can we hit that nail on the head? The “Lost Cause” ideology—not everyone may be familiar with what exactly that refers to. Can we define the Lost Cause?

David Blight: Well, John put his finger on the button because it’s the success of this set of arguments with Northerners that tells the story. The Lost Cause came into existence as a sort of cultural response to defeat. And no Americans other than Native Americans have ever been defeated quite as much as the white South, the Confederacy. So, immediately, in the wake of the Civil War and for the next twenty, twenty-five years, they needed a story to explain defeat. They needed a story to explain their poverty. They needed a story to explain loss on a terrible scale. And part of that story—only one part of it—became that they never really fought for slavery. The argument was that slavery was probably going to die out anyway. And on top of that it was never that terrible. The war, this argument said, only really came about because of fanatical abolitionists from the North forcing the issue into American politics and then forcing disunion by part of the South to defend its civilization. It was an effort to try to portray the Confederacy and the effort of the Confederacy as noble. As really the legacy of the American Revolution being carried out. So a benign slavery with well-clad slaves, even in a cotton field, is necessary to that tradition. At the heart of it also emerged a popular culture: enormously popular fiction and literature about faithful slaves—as odd as it seems in the twenty-first century, especially to young people—that readers all over the country and particularly Northern readers would buy into Thomas Nelson Page stories of faithful slaves who always had names like Uncle Billy and Aunt Harriet wistfully talking about the old days under slavery when everything seemed to be in order when “the master treated us well and now, in freedom, you know, it’s just chaos.” But it sunk deeply into popular culture, into visual culture, into popular literature, into politics, into every element of American life, such that by the time these amazing windows were produced they were produced by Northerners—Northern companies, Northern artists. Because if you were to depict the life of Calhoun, which is what these windows are doing, and his Fort Hill plantation, what is now Clemson in South Carolina . . . well, it was a civilization that was . . . it was a society and a plantation that was part of the cotton kingdom. This is where Calhoun was. So part of those stained glass windows depicting Calhoun’s life are not about his service to the country or his service to the political center, but were about his plantation. And the plantation in America’s past, in the popular imagination at that time meant reasonably contented black people in a cotton field doing their labor. There are no overseers with whips. There is no auction block. In the nineteenth century the most prominent visual images of slavery were the runaway slave— produced by the North before the Civil War—were the runaway slave, the auction block, and sometimes other depictions of slaves in a wilderness somewhere trying to escape, and then, lastly, the lash—whipping. That was the old abolitionists and there’s a lot of this stuff; visual imagery of slavery. But by the turn of the twentieth century it needs to be this benign civilization that’s now lost and gone.

“In the nineteenth century the most prominent visual images of slavery were the runaway slave, the auction block, sometimes other depictions of slaves in a wilderness somewhere trying to escape, and the lash.”

Benjamin Miller: Of course. So this is not atypical for the period in terms of how Northerners might have thought—

David Blight: Harper’s Weekly had run stuff like this back in the 1870s and 1880s, and not always that benign. But images of this older, now-gone civilization . . . that wasn’t gone entirely by any means. Cotton production revived very well by the early twentieth century. But, anyway. To associate this with Calhoun is because he had himself indeed owned a major plantation in central South Carolina.

John Stuart Gordon: And then this window is part of a larger composition and there are four or five windows that form this kind of suite together, talking about plantation life. The rest of the windows are flora, fauna of the South. But there is this group that depicts plantation life. And one depicts Fort Hill, Calhoun’s house. One depicts a slave cabin. One depicts a gin house where the cotton gin was. And you had then the slaves in the fields. So—

“We have yet to find the print source, but we just need to find a book on Calhoun’s life or a survey of the South where they have a chapter on South Carolina and these images are going to appear.”

David Blight: There’s a banjo player, too, isn’t there?

John Stuart Gordon: There’s a banjo player, which is a slightly different format—not a better message, but it doesn’t kind of fit into this series. And the handling of the imagery in this series is very similar. We have yet to find the print source, but, given that most of these windows were made after prints or illustrations I know out there, we just need to find it, is the book—probably a book on Calhoun’s life or a survey of the South where they have a chapter on South Carolina and these images are going to appear. These windows were being made as part of large orders. There are a couple hundred in each building on campus and Sterling library alone has two thousand windows like this.

David Blight: Mass production!

“If you look at it closely it’s a few pieces of glass. Even when it was fresh out of the studio, it was broken and reassembled. And I like that metaphor that they’re it’s depicting a past that never existed. And something that was inherently broken.”

John Stuart Gordon: Yes, so the artists are not going to struggle to create a new composition. They’re going to source composition so they can repurpose it. If you look at it closely it’s a few pieces of glass. One is slightly blue tinted one’s whitish tinted one’s a little green. So this was never a complete window. Even when it was fresh out of the studio, it was broken and reassembled. And a lot of these images are broken and reassembled. And I like that metaphor that they’re depicting a past that never existed. And they’re also depicting something that was inherently broken. So long before a worker in Calhoun’s dining room, Corey Menafee, broke the window, this idea of rupture and disruption was already present in the image.

Benjamin Miller: Ok, so we’ve been jumping around between time periods. But now that you’ve mentioned Corey Menafee’s name, let’s jump into the present. There’s a reason that this panel was broken. It didn’t happen by accident. John, what’s the . . . how did this come to happen?

“In 2016, a dining hall worker, Corey Menafee, got a broom, moved a chair over to the wall, stood on the chair and hit the window out.”

John Stuart Gordon: It was the summer of 2016 and this dining hall worker, a man named Corey Menafee . . . as he later recounts, he . . . his job has him located in that dining hall for long hours at a time. And you take in your surroundings if you’re in a space like that. Many of the people who just come in for a quick meal may not internalize the decorations as much. But he had the time to really study the windows and kind of see how problematic they were and how uncomfortable they made him. And the question of “Why is this imagery in an institution like this? Why do I have to sit here and look at it all day?” And as he recounted one day he just kind of snapped and was like, “You know, it’s coming down today.” And he got a broom, he moved a chair over to the wall and stood on the chair and hit the window out. And it’s just this moment of kind of like he’d had enough of looking at this image . . .

Benjamin Miller: I want to read . . . He was quoted in the New Haven Independent shortly after the incident and this quote really struck me. It’s pithy. He said, “It’s 2016. I shouldn’t have to come to work and see things like that.”

John Stuart Gordon: Yeah. It’s profound in its simplicity. He knew what he was doing was inappropriate. But, at the same time, the image is inappropriate, so they kind of cancel each other out. And the window broke out into the street at which point it became an issue of glass could have hit someone and New Haven police were brought in and it became a full investigation and this story snowballed from there.

Benjamin Miller: And you’ve included this in your book as a sort of an epilogue.

John Stuart Gordon: Correct.

Benjamin Miller: It’s not included in the normal catalogue of objects.

John Stuart Gordon: Correct.

Benjamin Miller: And it’s the final entry at the very end of the book.

John Stuart Gordon: Why?

Benjamin Miller: Why did you . . . I think we can all imagine why you felt it was important to include this in the book, but what was your thought process and how did you decide to do it in the way that you did it?

“When I did a survey of all the stained-glass windows on campus to find ones to include in the book these didn’t rank as coherent works of art in a formalist, traditional approach.”

John Stuart Gordon: It was a difficult decision. I initially wasn’t going to include this in the book. It was a hot button issue when I was writing this. It was still 2016–2017 and this action wasn’t alone. It was right in line with larger discussions on campus about race and representation, larger discussions in our culture about it. So it was kind of a flashpoint issue. And I didn’t feel I was equipped to handle it because I was still living in it myself. And yet, every time I would meet people and tell them I was writing a book about glass at Yale their first question was, “Oh, you mean the window?” And I finally realized that I’m going to keep getting that question and then once the book is out the question will shift to, “Why not that window? And why didn’t he want it in there?” For me, there was a problem, though. When I did a survey of all the stained-glass windows on campus to find ones to include in the book these didn’t rank as coherent works of art in a formalist, traditional approach.

John Stuart Gordon: None of the windows in any of the halls?

John Stuart Gordon: I have a window from Sterling library and one from HGS [the Hall of Graduate Studies], but not from Calhoun. And I have a Tiffany window from on campus as well. But for some reason . . . We have a couple thousand windows like this on campus so how do you choose? And this one wouldn’t have been on my initial list. So I had a hard time putting it into the book. And the book is roughly chronological, so then I had a second problem. The window as an object of the 1930s . . . you know, we now think about it as actually a really compelling example of Lost Cause ideology—the sustained racism of the kind . . . I mean, you could actually unpack in incredible ways. But I was like, “I don’t really know how to deal with this as a 1930s object.” What makes it so compelling is something that happened in 2016. So is it appropriate to make it be a 2016 object when the window is kind of refashioned into its new afterlife? That didn’t seem comfortable as well, and the fact that it needed to be unpacked and explored with probably a little more depth and sensitivity than most other objects in the book—it didn’t feel right to kind of squeeze it into a catalogue entry. So my editor and I decided to let it kind of sit on its own because it is a slightly different story than most of the other objects in the book.

David Blight: It has a politics to it.

John Stuart Gordon: Yeah.

David Blight: Perhaps most of your other works don’t. Although some may.

John Stuart Gordon: Some do. But the politics are different. And the fact that this is about an object’s afterlife is a slightly different interpretation from most of the other objects—

“And I reached out to a number of Calhoun alums and people who live in Hopper today and asked them what their memories were of this. Some people did remember it and were uncomfortable, and others had no idea. And whether or not you noticed it or were aware of it did not break down on racial lines, it did not break down on age lines.”

Benjamin Miller: Well, it has a political life today in a way that, while other objects may have political significance or cultural significance for their time, this remains relevant. In fact it is much more important today than it ever was when it was made.

David Blight: Ignored by thousands until it was broken.

John Stuart Gordon: And I reached out to a number of Calhoun alums and people who live in Hopper today and asked them what their memories were of this window and was struck by the varied reactions. Some people did remember it and were uncomfortable, and others had no idea. And whether or not you noticed it or were aware of it did not break down on racial lines, it did not break down on age lines. It was fascinating to see that just some people were aware and some people weren’t. But those who were aware had been uncomfortable for a long time.

Benjamin Miller: So, as you said, this was a rather different subject for you to approach from other subjects in the book. Sensitive. Challenging.

John Stuart Gordon: I was struck by the ideas of memory and transformation and the fact that something as seemingly benign as a windowpane could be so powerful, and the fact that a work of art could generate such emotion and such reaction. We seem to become anesthetized to images today; we’re so bombarded by images. The fact that an image could actually stir someone to action, could start a campus debate—I found that really powerful, but I didn’t know how to get from there back.

David Blight: It took the abstraction out of it. The way you tell it is fascinating. It took the abstraction out of all this ideology—whether it’s the act of the guy with the broom or the larger debate about the name of the college—it shows us that there are these confluences of events in society, actions by people, ideologies, art works, all kinds of things that can come together at once and cause a new politics. Cause a new turn that you can never predict. Who . . . How could you predicted, two and a half years ago, that we’d be sitting here—Or was it three years ago, already?—that we’d be sitting here looking at this broken object.

“We seem to become anesthetized to images today; we’re so bombarded by images. The fact that an image could actually stir someone to action, could start a campus debate—I found that really powerful.”

Benjamin Miller: Well, I think one way one way you might have anticipated that is to think about the way that people react to Confederate sculptures or Confederate statues. To my mind, as as an antiques and decorative arts person, it’s a great reminder of the power that physical objects have and how that dovetails so often with ideology, and it leads to an interesting sort of paradox for . . . John, for you as a curator, your job is to preserve historical objects. And here we have an object that was not only not preserved but it was intentionally defaced—destroyed, vandalized—and yet, we all understand the reason that it was vandalized, and I think it’s hard not to sympathize with that reason, with that motivation. And so, John, as a curator, how do you think about that? How do you grapple with that? With that conflict of priorities, of interests?

John Stuart Gordon: It’s a really difficult point and I feel conflicted about it daily. And the fact that we are still talking about this window—and I talk about this window a lot with people because it’s so powerful—I’m constantly conflicted. And I would say, actually, I don’t know how I feel about that, because I don’t want to say that this kind of action is all right or it’s justified. But at the same time I acknowledge that it has a purpose and I acknowledge the good that can come out of acts like this. And if you just broke a window or toppled a statue and walked away and never thought about the actions I’m not sure anything has been learned. So I can’t reverse the breaking of the window, but I can try to make sure we learn something from that and use that to start a different discussion. So maybe the next window doesn’t have to be broken but we understand more and have more open dialogue.

Benjamin Miller: Ok, I want to back up and ask a philosophical question. I don’t know if this is philosophical; maybe it’s a practical question. So, I’m a Yale alum. I spent four years on campus. Some of the pieces in your book . . . I recognize a few of them. Many of them I don’t, either because they were in a gallery that I didn’t visit or they were in storage or because they, like this window in Calhoun College, I might have just walked by and never noticed. So you’ve written an entire book about glass at Yale, and I want to know if all of the interesting glass on Yale campus were removed, were replaced with uninteresting glass, how would life on campus be different. For you, for undergraduates, for faculty, for residents. How would things change?

“I can’t reverse the breaking of the window, but I can try to make sure we learn something from that. And maybe the next window doesn’t have to be broken but we understand more and have more open dialogue.”

John Stuart Gordon: Well, certainly the art gallery would feel a little more empty because we would have lost some of our great objects. The residence hall, the library, the classrooms would be less interesting because they would have lost their stained glass. The science labs would be a little less effective because they would have lost their microscopes and their test tubes. It’s really everywhere. You would have lost big portions of the mineral display at the Peabody, although we know glass is not a mineral. It’s just one of those materials that is so ever-present that I don’t think you’d notice until it all went away. I have eyeglasses in my book. Does that mean we’d take all the eyeglasses away? This’d be a very different place if no one had eyeglasses.

Benjamin Miller: Thank you both so much.

Both: Thank you.

Benjamin Miller: That’s all for today. I hope you enjoyed it and maybe took something away from it. Again, photos are at themagazineantiques.com, and on Instagram @objectiveinterest. Thanks again to Stefan Nicolescu, to David Blight, and, of course, to John Stuart Gordon. I strongly recommend checking out his book, American Glass. It’s actually a page-turner, which is something of a rarity in the world of art books. The objects are fascinating, and the photographs are beautiful.

Today’s episode was edited and produced by Sammy Dalati. Our music is by Trap Rabbit. And I’m Ben Miller.

John Stuart Gordon is the Benjamin Attmore Hewitt Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery. He received his BA from Vassar College, MA from the Bard Graduate Center, and PhD from Boston University. Gordon works on all aspects of American decorative arts and material culture, but his specialties are silver, modernist designs of the 1920s and 1930s, and postmodernism. In addition to his curatorial work, he supervises the Furniture Study, the art gallery’s expansive study collection of American furniture and wooden objects.

David W. Blight is professor of American history at Yale University, where, as of 2004, he is director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. He previously taught at Amherst College for thirteen years, and is the author of a new, full biography of Frederick Douglass published by Simon and Schuster: Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

Stefan Nicolescu is the collections manager at Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. A graduate of Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania, Nicolescu moved to the United States for a post-doctoral research position at Washington StateUniversity, after which he got immersed in radioisotope dating, first at Yale, then at the University of Arizona. His publication list includes more than sixty peer-reviewed papers, conference abstracts, book chapters, and field trip guides.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com.