In the third episode of The Magazine ANTIQUES’ podcast Curious Objects, host Benjamin Miller interviewed Katherine Purcell, principal in the London jewelry firm Wartski. A peerless scholar and an engaging storyteller, Purcell gives us the particulars on a magnificent enameled necklace by René Lalique, the “genius of art nouveau jewelry.”

Necklace by René Lalique, c. 1898. Gold, enamel, and pearls. Photograph courtesy of Wartski.

Benjamin Miller, Host of Curious Objects & the stories behind them

Benjamin Miller is a director of research at the silver firm S. J. Shrubsole, and one of the rising young stars of the New York art and antiques scene. An urbane compère in the mold of Dick Cavett, Ben combines the friendly graciousness of his native Tennessee with the polish of his Yale education.

Katherine Purcell. Courtesy of Wartski, London.

Katherine Purcell is Associate Managing Director of Wartski and her specialty is French nineteenth-century jewelry. She has contributed various articles to the Antique Collector, Apollo and The Magazine ANTIQUES on the Parisian jeweler firm Falize, the master of art nouveau René Lalique, and on the influence of Japanese works of art on Western jewelry and goldsmiths’ work. Her definitive study Falize: A Dynasty of Jewelers was published in 1999 and her translation of Henri Vever’s three-volume French Jewelry of the Nineteenth Century in 2001. Amongst the exhibitions Purcell has curated for Wartski are Fabergé and the Russian Jewellers (2006); Japonisme from Falize to Fabergé, the Goldsmith and Japan (2011); and Fabergé – A Private Collection (2012).

Katherine Purcell: René Lalique stands apart from all other jewelers in that he is quite widely regarded as the genius of art nouveau jewelry.

Benjamin Miller: Curious Objects is sponsored by Reynolda House Museum of American Art, one of the nation’s most highly regarded collections of American art, on view in the unique domestic setting of the 1917 R. J. Reynolds mansion. Browse the art and decorative arts collection at reynoldahouse.org—that’s R-E-Y-N-O-L-D-A house dot org—and visit in person in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Welcome to another episode of Curious Objects & the stories behind them, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m your host, Ben Miller, and I’ve got a great show for you today. I’m talking with Katherine Purcell of the firm Wartski in London about a fascinating necklace by the art nouveau jeweler René Lalique. Katherine is a phenomenal storyteller, and what she has to say about this piece really brings the people and objects of art nouveau and the Belle Époque to life. In some ways, it’s really changed how I think about this whole period, and I really think you’ll enjoy it. So I encourage you to visit themagazineantiques.com, where you’ll find an image of the necklace and some other images and links. Finally, as the host of a new podcast, I’m relying on you guys to tell me what you like and what you don’t like and what you want to hear more of, so, please, if you have any comments or questions, send an email to podcast@themagazineantiques.com. I’ll read it, I’ll respond to you, I really appreciate it. Ok, let’s get started!

Benjamin Miller: Katherine Purcell, thanks so much for talking to me. It’s a real pleasure.

Katherine Purcell: Thank you for inviting me.

Benjamin Miller: We’re talking about a piece of jewelry, although to call it a piece of jewelry is maybe giving it short shrift because it’s really . . . it is, it’s a necklace, a pendant necklace, but it’s also—I think anyone would agree—a work of art. It’s a piece by a French jeweler from the nineteenth century. And I’m wondering if you can give a physical description for our listeners.

Katherine Purcell: Absolutely. Well, it takes the form of a pendant on a long chain. The pendant itself is centered with a female bust portrait of a young woman. Most striking is the fact that she is enveloped in branches supporting pinecones and needles. The pendant is suspended with three pearls, and the chain work echoes the motifs, also bearing pine cones and needles, interspersed with pearls. The piece doesn’t have a single gemstone in it. It is entirely decorated with enamel in terms of the female portrait. The enamel is principally in dusky shades of blue to grey, and her hair is very dark, almost black in color, and the pine cones themselves are of enamel which has been etched to give them volume. The branches so envelop her as to almost reveal her face amidst the branches. She’s actually clasping one of the branches in her hand. So that is the first appearance of the piece, if you like.

Benjamin Miller: I want to come back to the physical form, and the design, and the aesthetics. But who was the woman?

Katherine Purcell: Well, that is the key question because I’ve discovered that the woman in question was actually his muse. Her name was Augustine-Alice Ledru. They met in her father’s studio because her father was actually the bronze foundry maker to René Lalique’s bronze works. And at the time that this particular pendant was carried out, they had not yet married. They actually met in 1890 but married in 1902. And we, fortunately, have this particular jewel recorded in contemporary periodicals because it was featured at the 1900 Paris Exhibition and evidently caused such a stir then that it was reproduced in a number of contemporary journals including L’Exposition Universelle de 1900, by Gustave Geffroy, which was published in 1902 but was a resumé of the entire exhibition, and, equally well, Henri Vever in his three-volume history of French jewelry chose to illustrate it.

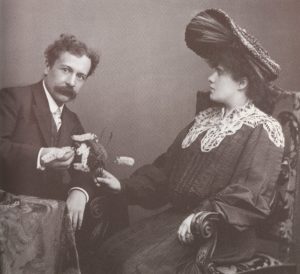

Photo of Lalique and his wife and muse, Augustine-Alice Ledru, c. 1903 Archives Lalique, Musée

d’Orsay.

Benjamin Miller: Which—I should interject—we have in English thanks to your work.

Katherine Purcell: Yes, I did translate the three-volume history into English. That’s correct.

Benjamin Miller: So, are these publications . . . how did you discover the identity of this woman? Is it because of those publications?

Katherine Purcell: It wasn’t the publications that actually held the key. The first clue that I had is the fact that at the base of the pendant, the actual little cutout form from which the center pearl is suspended, is actually a cutout heart, and I’d actually never seen this feature in a jewel by René Lalique before. It led me to think that there must be some kind of romantic association between him and the sitter if you like. And I started to read further accounts of female figures in his jewels, and it turned out that Augustine-Alice did feature in a number of his works of that period, particularly before they got married, and he was obviously very inspired by her.

Benjamin Miller: After marriage, it’s hard to motivate yourself.

Katherine Purcell: Well, we hope that that’s not the case. But, certainly, the majority of the work seemed to have been created in those earlier years.

Benjamin Miller: In the courtship?

Katherine Purcell: During their courtship, and in fact, very usefully the Corning Museum of Glass has abasse-taille featuring her, signed by René Lalique. Which we have always known to have been of her, and she had quite a distinctive profile with quite a pronounced chin and this is borne out by photographs of the two of them together. So this is an incredibly personal jewel. And it’s by no means incidental that the motifs in the jewel are actually fir cones and pearls, because pinecones, in the language of botany, stands for eternity, and the pearl, because Venus was born from a pearl, symbolizes love.

Benjamin Miller: Of course.

Katherine Purcell: So, you already have eternal love in this jewel. But the heart, notwithstanding, rather charmingly . . . as you turn the jewel over you actually find a mirror image of the jewel in chased-engraved form. Which is very typical of René Lalique’s attention to detail. The ability, and, in fact, the priority he gives to all aspects of his jewels, whether, for example, making a piece from plique-à-jour enamel but actually designing it as a choker so only the wearer would know that it carries his great sophistication of plique-à-jour enamel which is immediately lost when you wear it right against the skin.

Plique-à- jour enameled Plaque de Cou by Lalique, c. 1900. Courtesy Wartski, London.

Benjamin Miller: Sure.

Katherine Purcell: So in the same way, only the wearer would have known, in this particular instance, that the jewel was so elaborately finished on the reverse.

Benjamin Miller: That’s a really special feature and makes the piece all the more intimate to know that there was an element that was reserved only for the person for whom it was made. I don’t know if you find that in contemporary jewelry so often.

Katherine Purcell: Well, as we know in the world of jewelry, the more you handle, the more you know that the first thing you do is actually to turn the jewel over, because if it’s beautifully finished on the reverse it’s an indication that it’s going to be fantastically made on the front as well. It’s the attention to the unseen detail which is always the key.

Benjamin Miller: It’s like looking under the hood of a car.

Katherine Purcell: Yes, that’s correct, in another field. So I would say now that we have reached a different age that does not involve years . . . years of apprenticeships, for example, as happened in the nineteenth century in all forms of the decorative arts. Now, unfortunately, time is money and so it is actually quite rare to find pieces that are as elaborately finished on the reverse as they are to the front. A very few contemporary . . . let’s say, “artist jewelers” . . . can actually put that time and effort into completing something as fantastically. It may be very beautifully finished, but it wouldn’t be carried necessarily to the same extent as you would see it on front.

Benjamin Miller: Right.

Katherine Purcell: So this was something that really René Lalique prided himself on.

Benjamin Miller: And, he stood above his contemporaries even in that regard.

Katherine Purcell: He did. Although I would say that there were some extraordinarily talented jewelers and enamelers working at the time, and all of them—be they Fouquet, Henri Vever, Frédéric Boucheron—had known this era of immensely long trainings in the different fields that they specialized in. And therefore when one reads accounts of Alphonse Fouquet and how at the age of twelve he was literally on bread and water sleeping under the workshops as he trained to become a jeweler—those stories I am sure are not isolated, and therefore they were trained with this exactitude to detail. It so happens that René Lalique had other talents, such as an extraordinary imagination.

“Rene Lalique stands apart from all other jewelers in that he is quite widely regarded as the genius of art nouveau jewelry.”

Benjamin Miller: Hmm.

Katherine Purcell: He was very lucky in benefiting from some very early patronage that helped his career enormously. But René Lalique stands apart from all other jewelers in that he is widely regarded as the genius of art nouveau jewelry.

Benjamin Miller: This piece was made around 1900 . . . today, it’s at Wartski . . . where has it been in between?

Katherine Purcell: Well, that has been a bit of a mystery. We know that it has been in a private collection for a number of decades. Beyond that, we don’t know. From the time that it was owned by René Lalique’s wife until it arrived in this private collection, we don’t know. Indeed, it has been lost for a number of decades because when Sigrid Barten wrote her catalogue raisonné on René Lalique it is simply featured in black and white photographic form, and the photograph is actually the very one that was illustrated by Henri Vever in his book, which was published in 1908. So, there was no color image available of this work. So to discover first of all the palette in which it was carried out was a real revelation. It’s in absolutely perfect condition.

Benjamin Miller: Now, you mention that there are no precious gemstones in this piece and that’s typical of art nouveau jewelry, is it not?

Katherine Purcell: That is. But I have to say that René Lalique was one of the very first to embrace this particular aspect of Japanese art. One can’t talk about René Lalique without talking about Japan. Japanese works of art were first seen in Paris in 1867 at the L’Exposition Universelle when for the first time the Japanese were able to organize their first pavilion truly representative of their works of art. And this was a real revelation to fellow artists from all over the world, but particularly the French, who fought over these Japanese works of art. And not least for the sense of artistry that was imbued in the most modest materials. So be it basket weaving, be it the carving of common cow horn, it applied itself into every single type of material and this was something that was not at all lost on René Lalique. And, as you rightly say, this particular jewel doesn’t have a single precious stone in it, not even a semiprecious stone. It is literally just enamel and pearls. And he was so inspired by this that he himself started exploring the use of ivory and common cow horn in his jewelry, as well as tortoiseshell. And he exhibited for the first time in 1897, his display almost entirely devoted to combs carved from tortoiseshell, and ivory, and horn, which caused a sensation. Nothing had ever been seen like this before, such artistry in very, very modest materials. And I think that this certainly led the way for an awful lot of other artists, such as Lucien Gaillard, who equally well started creating combs made from similar materials. I also think that the whole attitude shifted in terms of the appreciation of different types of very time-consuming techniques, such as different types of enamel which were certainly not intrinsically valuable but commanded a huge amount of time. The technique of plique-à-jour enamel, for instance, the building up of many, many layers of enamel from a specific contour, is hugely time-consuming, and, as I said, is very difficult to actually wear in such a form that it’s instantly revealed. So one could have, for example, a comb made of plique-à-jour enamel . . . this would be the perfect tool, because worn high in the hair—and they had very large coiffures at the time—

Benjamin Miller: Of course.

Katherine Purcell: —one would see the daylight coming through the enamel. And, of course, you then had that rich panoply of vibrant colors immediately to be seen as you walked into a room. However, plique-à-jour enamel is a very difficult form of jewelry to wear, but obviously, it’s also quite fragile. It’s instantly lost if you wear it as a choker, but equally well if you wear it as a bracelet or a pendant because it would be constantly against a surface. So, it was, nevertheless, something that was very much explored, as were other types of enamels such as champlevé enamels, and so on, at that time. So, I think this use of non-intrinsically valuable materials was very much something that was symptomatic of Art Nouveau. You’re quite right. I would just perhaps like to just emphasize once again why René Lalique was really a precursor in everything he did, and to go back to the influence of Japan in his work, because it wasn’t exclusively the use of non-intrinsically-valuable materials that actually was so influenced by Japanese works of art but also, I would say, the scrutiny of the world in all its forms. The sense of the duality of nature, for instance. In Japanese art, whether you take a netsuke or a bronze, none of the craftsmen were as shy about showing the decay of the natural world. And this is something that René Lalique, in his close scrutiny of nature of a child, would have very much taken on board. But, I think to take it into the field of jewelry was something quite unknown and therefore when he—and I’m talking about Lalique now—shows, let’s say, a tiara that consists of branches of fern, and he’s showing them under the weight perhaps of water, he’s not showing them in the way that one might traditionally think of a botanical motif. When he also will take a leaf and show it gnawed away at by insects—

[His] close observation of nature was miles apart from the full-blown roses that one might have seen in diamond-set jewelry in the eighteenth or nineteenth century.

Benjamin Miller: Right.

Katherine Purcell: —this is something that was entirely new. And this close observation of nature was miles apart from the full-blown roses that one might have seen in diamond set jewelry in the eighteenth or nineteenth century.

Necklace by Lalique, c. 1900. Carved glass and opal. Courtesy Wartski, London.</em

Benjamin Miller: Sure, the heavily romanticized depictions.

Katherine Purcell: Exactly. It was this immense study of nature that was very much part of him, and I think stimulated by seeing Japanese works of art, and equally well in some of the landscapes that he showed. This duality was shown in everything. If he showed a very poetic looking winter landscape, for example, with a landscape of fir trees with snow on the branches, the contours of the actual pendant would consist of the gnarled branches and tree trunks split right down to the roots, which would be shown at the base of the pendant from which a pearl was suspended. This showed both sides of the natural world if you like, you didn’t just stay with the beautifully snow-capped mountains. There was always something going on underneath, and in the same way that one could see the beauty in the savagery of the animal world, this duality was also shown in the female figure. One of his most famous pieces in the Gulbenkian collection consisted of a woman turning into a dragonfly, but very menacing in that she appears to have claws for fingers and becomes almost monstrous if you like. And I think this was something that had never been explored before in jewelry and was something completely new.

Benjamin Miller: And that’s a stark contrast to, for example, Louis Comfort Tiffany, who also drew heavily on Japanese inspiration. But his glass, the famous stained-glass windows you can find in museums around the world—

Katherine Purcell: Yeah.

Benjamin Miller: —these are beautiful garden scenes. These are unblemished depictions of nature. These are perfect sunsets, where every bird is properly placed, every flower is at the right proportion. Why do you think Lalique, drawing on some of these same sources of inspiration, went to the raw, unbounded brutality of nature alongside the obvious, romantic, and aesthetic attraction of it?

Photo of Lalique’s pine trees in Clairefontaine, near Rambouillet, France, by René Lalique, c.

1898. Archives Lalique, Musée d’Orsay.

Katherine Purcell: That’s a very good question. Certainly, when he was very young, he’s known to have been spending the majority of his childhood drawing nature as he saw it. He felt that the truth to nature was very, very important, and his early drawings do show all kinds of insects and plants that had never really been shown before. But he is trying to really show that there are two sides to nature. It’s going to take a certain type of woman to wear something that doesn’t show necessarily the beauty of nature but would have probably appealed to certain people like Sarah Bernhardt because they did not want to wear jewelry that was harking back to what’s been made centuries before. They wanted to make their own mark. And this was a way of doing it, not just through their behavior but immediately announcing through what they wore that they were with the new fashions, with the new designers, and particularly with René Lalique. The influence of nature on his work is hugely important, and, in fact, the introduction of pine cones as the motif in this particular jewel is interesting in terms of date because in 1898 René Lalique acquired a property in Paris, to the south of Paris, called Clairefontaine, which was populated with fir trees. And it’s from that date that he started to incorporate that motif in his work. There’s a watchcase in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs entirely decorated with pinecones. There’s a series of drawings by him showing them. And his first attempts at photography, in fact, take place at Clairefontaine, where, interestingly, he takes images of the lower part of the tree trunks and the lowest branches. He doesn’t take the entire tree. And this, of course, is very reminiscent of the fragmented depiction of nature and images as seen in Japanese art. That strange perspective in which one doesn’t see a whole image but a fraction of it and then that draws you in. This is very much how his first photographs of the pine trees are taken. The motif was introduced from about 1899, I’d say a year after he bought the property. So, yes, I have to say that’s probably why I also consider René Lalique to be the genius of art nouveau because it’s to do with imagination and materials. And, of course, a quality of craftsmanship that is pretty much unequaled.

“[His] close observation of nature was miles apart from the full-blown roses that one might have seen in diamond-set jewelry in the eighteenth or nineteenth century.”

Benjamin Miller: We’re just going to take a quick break now. I really hope you’re having as much fun listening to this as I did talking to Katherine. One of the great perks of talking to antiques dealers is they’re natural-born storytellers, and Katherine is no exception. When we come back, we’re going to talk a little bit about the context behind Lalique’s work, and some of his contemporary artists: Rodin and others who had strong influences on Lalique’s work. I want to encourage you and remind you to go to themagazineantiques.com and look at some of the images that are posted of the necklace and other Lalique work. As wonderful and colorful as Katherine’s descriptions are, you deserve and you owe it to yourself to see a picture of this necklace. It’s a truly stunning object and you will never forget it. So go to themagazineantiques.com, look at the images, we’ll be right back.

Thanks to our sponsor for this episode, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, celebrating its fiftieth anniversary with a new publication, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories, that takes readers behind the scenes of one of the nation’s most prestigious collections. On the Albert Bierstadt masterpiece Sierra Nevada, the museum’s founder, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, remembers traveling to see Bierstadt’s views for herself. She wrote, “it was as though I rwas sitting in a theater with an intense drama enacted in front of me. I knew at once that Bierstadt expressed in his paintings exactly what I felt.” Escape to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to experience the unique views of Reynolda House Museum of American Art. American art masterpieces surrounded by centuries-old decorative arts in an American country home. Reynolda House Museum of American Art. Reynoldahouse.org.

Welcome back. Thanks again for listening. Don’t forget to leave us a rating and subscribe so you don’t miss any future episodes. And, again, if you have any comments or suggestions, send an email to podcast@themagazineantiques.com.

Benjamin Miller: This is something I haven’t really thought about before, but what kind of prices did these jewels—this one, of course, was made for someone he had an intimate relationship with and so not presumably on the private market—but jewels that Lalique was making . . . these were a new form, they were a new idea, they didn’t incorporate stones that carried value intrinsically—that kind of prices were these pieces fetching?

Katherine Purcell: They certainly commanded high prices, even in their day. I have to say so at this early point I was talking about the patronage that he was fortunate enough to attract. It was very fortunate for him that the great actress Sarah Bernhardt discovered his work in the early 1890s, in fact in 1892, because it allowed him to make not only theatrical jewels for her but also very personal pieces of jewelry that would make his name better known to a wider clientele. Who would also perhaps not be frightened by the more avant-garde aspect of his jewels because certainly for a woman to be wearing a female form on her, as a piece of jewelry, must have been quite osé at the time. Whereas previously one was quite happy to wear botanical motifs, which really were the most common form of jewelry ornament in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. The idea of actually a woman wearing a sort of naked female figure carved from ivory, as one found in works by René Lalique, or by Gaillard, or Vever, would have seemed extremely bold and would certainly not have suited every woman. And I think it took a particular type of person who was prepared to make a statement in public about how avant-garde she was in terms of wearing something like this.

Benjamin Miller: This being Sarah Bernhardt.

Katherine Purcell: I think, also, the fact that the artistic world was very much a close one at that time—and, for example, Reneé Lalique and Auguste Rodin knew each other—one found, for example, certain subjects in each other’s work echoing the other. Everyone is familiar with the Rodin sculpture entitled The Kiss. Well, René Lalique himself carried out two or three jewels in which the center section are male and female kissing.

Benjamin Miller: It’s fascinating for me to hear about these relationships between a jeweler and artists.

Katherine Purcell: Yeah.

Benjamin Miller: Which again, you don’t necessarily think of as being very closely connected fields. But at his time, at least for Lalique, it was.

Katherine Purcell: Yeah, and they did know each other. I mean, I’ve read a book of correspondence of René Lalique’s in which he talks about going to Rodin’s studio. So, in fact, it’s no coincidence that Rodin and Lalique should have known each other given they both did work in bronze. Rodin obviously so, but Lalique did create works in bronze, and they shared, amongst others, the bronze foundry maker Ledru. Interestingly enough, Sarah Bernhardt herself carried out works in bronze, too, and was very interested in sculpture. So one has this great connection between different art forms, different artists. And, similarly, it’s not a coincidence that Sarah Bernhardt’s theatrical posters were all carried out by Alphonse Mucha, because, interestingly, the very flattened form that you see in the jewel we’re looking at now, with the very curvilinear treatment of the hair which helps you date it to about 1900, is very much the echoing of the flattened form one finds in the graphic arts of the period. And, it’s particularly—

Benjamin Miller: Interesting.

Katherine Purcell: Yes, the theatrical posters that Alphonse Mucha created for Sarah Bernhardt. And were one to look at this pendant in complete isolation, it’s that line of the hair that would be the total giveaway in terms of the dating of the piece.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, right.

Katherine Purcell: Because, it’s not the palette itself that would tell you that it was necessarily 1900, or her attitude. It is really this extraordinarily stylized treatment of the curves in her hair which really does remind me of the treatment of something one would see in a poster.

Benjamin Miller: That’s fascinating. So there are influences both from the most three-dimensional art form, that is, sculpture, and then the most two-dimensional art form, which is graphic design.

Katherine Purcell: That’s absolutely right. What I have omitted to say regarding this jewel is that quite apart from the decoration which is born on the back of the pendant, it also bears a brooch fitting so the jewel can be worn in its detached form from the chainwork as a brooch by removing the two bolt rings at the top of the pendant. One can wear it as a very long sautoir form of chainwork. This chain is over a meter long, and it is definitely the longest chain I have ever seen in René Lalique’s work. And, interestingly, it can be worn as both because one of the great fashions at the time was to wear jewelry in such a way that the chain work could create rather artistic loops to it, and what one can also do is actually hang the chainwork around the neck. And rather than let the pendant hang, actually raise it to the throat and pin it there, because by so doing you would then create two very artistic arches either side of the brooch. It also means that it would be seen at a height where it could be admired because obviously in its long form it hangs so low that one really misses out on the iconography, and it’s very possible that that is how it was worn in its time.

Benjamin Miller: That’s interesting because to see a jewel made that way today, one would think it was convertible, that it was intended to be worn either as a brooch or as a pendant, but in this case maybe it was both at the same time.

Katherine Purcell: I believe it could have been worn as both at the same time. It’s also intriguing that this very long type of chainwork would have been very suited to the new fashions of the day. Because with the very fashionable designer Charles Worth, who started creating dresses that did not require the wearing necessarily of corsets and actually were straight down to the ground these very elongated forms would have been perfectly adapted to wearing very long necklaces. And when one looks at the fashions of about 1900–1905, it’s exactly that, almost a kind of Greek-style dress in terms of no wasting. And therefore perhaps this is very much the precursor of those long sort of necklaces one finds during the année folles of the 1920s, as well. So, there’s an awful lot going on in the design of this jewel and the iconography of this jewel. The way it relates, in fact, in terms of art, be they painting or pastel, I have to say there’s something very much about this attitude of this female figure with her eyes closed in a kind of mystical mood which reminds me very much of the pastels that the symbolist artist Odilon Redon actually created some five, ten years later. And, similarly, in his pastels, you find female figures drawn to about this length—bust length—but totally enveloped with floral motifs, very vivid colors. But they have a mystical presence to them, and he was one of the foremost symbolist artists if you like. And it’s almost as if Lalique was a kind of precursor to this. I can only assume that Redon would have been familiar with Lalique’s work of art because everybody knew Lalique in 1900. His display caused such a sensation. It was something that the world had never been seen before.

Benjamin Miller: Yeah.

Katherine Purcell: The fact that so many artists actually chose his stand as a basis for some of their most famous works of art . . . There’s a particular graphic artist called Felix Vallotton who actually created this extraordinary black and white rendition of people just literally looking into his stand, and what you see is his stand in the background and all these bodies literally staring into the showcase in total astonishment.

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

Katherine Purcell: And one can understand why it caused such a sensation then because the descriptions at the time are very, very detailed and speak of bats hanging from the ceiling of his stand and gauze backdrops. And, furthermore, the front balcony area of his stand, as it were, consisted of several bronzes of female figures that appeared to be turning into something far more grotesque carried out in wrought-iron work.

“He could let his imagination go wild [because] he did not have to have his work defined by the fact that it had to be wearable.”

Benjamin Miller: Yes. These are pictured in Vever’s book.

Katherine Purcell: Absolutely.

Benjamin Miller: And they’re very striking.

Katherine Purcell: They’re very striking. And once I had the opportunity to actually see some of them come up separately for sale, and I believe there might be one even in the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon.

Benjamin Miller: Okay.

Katherine Purcell: They are monumental. And one can understand the surprise of people when they actually first saw these because this was such a long way from the traditional displays of jewelry at the time. One of the reasons why people so gravitated towards his stand was that Lalique was able to borrow back from one of his major patrons, Calouste Gulbenkian, some pieces that he had made for him. Now I have to say, Calouste Gulbenkian was an Armenian banker who had very quickly recognized the extraordinary talent and imagination of René Lalique and acquired works from him that were not going to ever be worn. They were actually going to be displayed on walls, in the middle of his collection of Holbeins, Ingres, and other such masterly painters.

Benjamin Miller: Wow. So moving even further now in the direction of art. Maybe in contrast to jewelry.

Katherine Purcell: Absolutely. I mean, even Calouste Gulbenkian himself saw them as works of art immediately. And so not only did he acquire some of the pieces that René Lalique had made, but he was also able to commission works from René Lalique where Lalique had full knowledge that he could let his imagination go wild because they actually could be totally unwearable.

Benjamin Miller: Hmm.

Katherine Purcell: And this explains, for instance, one of the wilder pieces in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, which consists of a tiara composed of a cockerel’s head clutching an amethyst. Fantastic chokers decorated with lakes consisting of opal and the tree trunks shimmering in chased gold. One also found corsage ornaments consisting of intertwined snakes which suspended ropes of pearls from their gaping jaws that measured half a meter long. And all these rather macabre—

Benjamin Miller: (laughter)

Katherine Purcell: —types of jewels that I don’t think any woman would have liked to wear . . .

Benjamin Miller: Those might fit in on the red carpet these days.

Katherine Purcell: Well, who knows! I mean, certainly, if one wanted to cause a sensation. This was a huge feather in René Lalique’s cap, that he was able to create these extravagant works of art that were being entirely financed, that were being borrowed back for exhibitions, and, therefore, was a great sort of publicity coup for him.

“Lakes consisting of opal . . . tree trunks shimmering in chased gold, corsage ornaments consisting of intertwined snakes which suspended ropes of pearls from their gaping jaws that measured half a meter long . . .”

Benjamin Miller: Mhmm.

Katherine Purcell: But that he did not have to have his work defined by the fact that it had to be wearable—I think that makes a very big difference. And these are the works, frankly, that are his most famous still today.

Wartski exterior. Courtesy of Wartski, London.

Benjamin Miller: One of the things that’s always been interesting to me about Wartski is how well-researched all of your objects are. And, I’ll say to listeners: if you have the opportunity to visit Wartski in their shop, or at one of the shows where they exhibit, if you pick out a piece that you like the looks of and ask about it, odds are you’ll hear a wonderful story about it. And that storytelling, I think, is such an important part of being a dealer in antiques and jewelry—to be able to sell not just the object, but the aura and history and the people who have owned it and used it. Is that part of what draws you to the discipline?

Katherine Purcell: In fact, my encounter with Wartski was a totally chance one because I had studied history of art and I wanted to work with paintings and sculpture. And it’s quite by chance that I found myself being interviewed at Wartski which I thought at the time was a picture gallery. Because we never used the word “jewelry” in publicizing a position, for security reasons. And I, therefore, thought that’s where I was coming to for my interview and was absolutely amazed to find the only work of art in terms of painting was one of Queen Alexandra. And I had never heard of Carl Fabergé. I was a total hippie and had no desire at all to look at jewelry, never mind work with it, and was incredibly fortunate in working with two people like Kenneth Snowman and Geoffrey Munn—who was embarking on his first book at the time—because their knowledge was monumental but more than anything their passion was contagious. They were incredibly generous with their knowledge and they encouraged me to pursue any form of research that I wanted to, in my own time if I were interested in anything. And slowly began to really look at jewelry for myself, not from a gemmological point of view because I was always very much drawn to the artistry on jewelry. And it was the craftsmanship involved and the techniques that really drew me, as well as the inspiration behind the pieces.

Wartski interior. Courtesy of Wartski, London.

Benjamin Miller: I want to wrap up by asking a couple of questions that I ask all of my guests, and one of those is . . . For a piece of advice that you would give to a collector who’s just starting out in the field, someone who has maybe just encountered Lalique, or art nouveau or someone who is just getting interested in jewelry of any kind—what’s a piece of advice that you would give to someone who’s just feeling their way into this area?

Katherine Purcell: I would say handle as much as you possibly can. One can read as many books as are available, one can look at as many images on the Internet as you care to . . . and, of course, now that’s a very useful tool. But it’s the handling of the piece, in the end, that will give you the most possible information. Examine exactly how it was put together, how many techniques are involved in the work, how is it built up, the weight, the choice of materials. Nothing is chance. So it’s by handling as much as you can and being able to compare pieces, that really is how you learn the most. And be brave. Walk into jewelry shops, however intimidating they look. Go and handle whatever you can before auctions that are available to you. It does take bravery because I know that I was very shy about doing such things myself but that is really the only way to learn. It’s the hands-on experience. The more you handle, the more you can also tell whether something has been tampered with in some way.

Benjamin Miller: Sure.

Katherine Purcell: Or whether you feel whether the texture of something feels slightly awry. Whether you suspect it may have been re-enameled, for instance.

Benjamin Miller: Mhmm.

Katherine Purcell: Whether marks, maker’s marks, date marks, may be superimposed. Whether certain marks may have been etched out, even. The most abominable things happen that you would never guess at when you’re starting out. And I think it’s only by close examination that you will learn the most. But it does take a lot of bravery.

Benjamin Miller: I am very well familiar with that. But there are plenty of friendly jewelry dealers.

Katherine Purcell: Well, we pride ourselves on being friendly jewelers. I mean, I have hugely benefited from that myself, and we’ve helped so many people in their projects and theses that they might be writing, and we feel so blessed ourselves that we were given this chance to work with people who are so generous with their knowledge. And, the more information that you can give out about things and help people, it always comes back to you. It always . . . somebody will remember you and will be thrilled to show you when they have something interesting that you can learn from; that you will feel as passionate about as they do. And that is something that, really, I hope is part of the Wartski ethic: really trying to communicate to people why we are passionate about the pieces that we were lucky enough to have.

“Handle as much as you possibly can. One can read as many books as are available, one can look at as many images on the Internet as you care to, but it’s the handling of the piece in the end that will give you the most possible information.”

Benjamin Miller: Now, for more experienced collectors who might be listening right now, what’s a mistake that you sometimes see experienced collectors make that you would caution against?

Katherine Purcell: I think when one starts off as a collector, one inevitably starts off fairly modestly, because your means are probably quite modest when you start off.

Benjamin Miller: Sure.

Katherine Purcell: And then as you learn your tastes become more and more refined and one becomes braver about buying more significant pieces. What can then be difficult is actually refining your collection to rid yourself of the first pieces that you acquired, because they may have all sort of rather nostalgic connotations to them because it’s the first piece you bought.

Benjamin Miller: Of course.

Katherine Purcell: But there’s no doubt that what makes the strength of a collection is the universal strength of the pieces. And sometimes one comes across collections where there are, let’s say, five or six masterpieces, and then there are maybe more pieces that are more modest or middling pieces. And I would always urge a collector, if they can, to perhaps just go for the very best, because, in the end, it’s the very best that will really hold their own in whatever context.

Benjamin Miller: Well, Katherine Purcell, thank you so much for joining me. It’s been a real pleasure talking.

Katherine Purcell: It’s been my pleasure, too. Thank you.

Benjamin Miller: Curious Objects is sponsored by Reynolda House Museum of American Art, one of the nation’s most highly regarded collections of American art, on view in the unique domestic setting of the 1917 R. J. Reynolds mansion. Browse the art and decorative arts collection at reynoldahouse.org. That’s R-E-Y-N-O-L-D-A house dot org, and visit in person in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

That’s all for today. I really hope you enjoyed it. I want to remind you one more time to go to themagazineantique.com to look at some pictures. You won’t regret it. And, again, send any feedback you have to podcast@themagazineantiques.com. If you liked what you heard, don’t forget to leave a rating on iTunes or whatever app you’re using to listen—it really helps me out—and don’t forget to subscribe so you get all the future episodes. We’ve got some great pieces coming up for you. In the meantime, Curious Objects is a podcast from The Magazine ANTIQUES, today’s episode was edited by Sammy Dalati, our music is by Trap Rabbit, and I’m your host, Ben Miller. Till next time.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com.