Sometimes an artwork can be too famous. Over time, such works tend to become roadblocks to a deeper and fuller understanding of an artist’s full body of work. Edvard Munch’s icon of angst, The Scream (1893), is one of those universally recognized images that often overshadow much of the artist’s formidable achievement. Fortunately for Munch and his legacy, a number of recent museum exhibitions have served to rectify the situation by practically sidelining The Scream. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2017–2018 exhibition, Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed (titled after a late self-portrait), centered on forty-three works, mostly portraits and figure studies that reflect the Norwegian artist’s personal struggles—familial losses, emotional turmoil, bouts with alcoholism, and periodically fraught relationships with lover and with humanity in general.

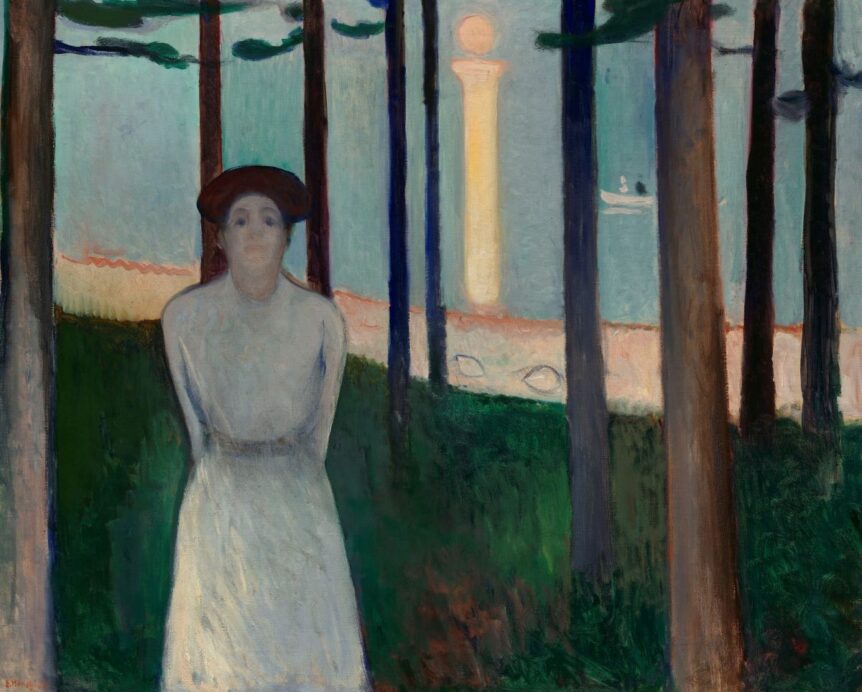

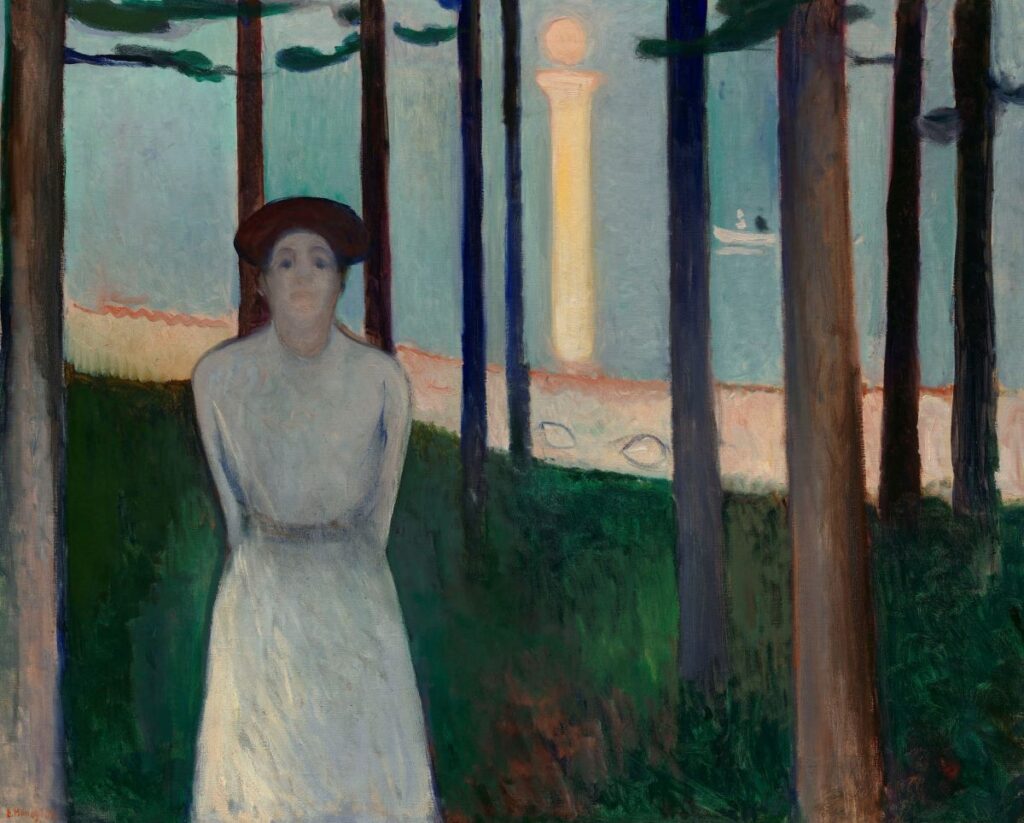

Currently on view at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth is a dazzling show of more than seventy-five works that explores in detail the artist’s intensely imaginative view of humankind’s communion and conflict with nature. In the present age of anxiety over the prospect of climate change, the theme could not be more apropos. The show, which is debuting at the Clark before an international tour that will take it to museums in Germany and Norway, convincingly conveys a spiritual connection to the earth and to the cosmos—the pantheistic beliefs that Munch held dear and clearly expressed in an inimitable way. Among the show’s highlights, nocturnal scenes such as Summer Night’s Dream (The Voice), and Starry Night (1922–1924) reveal the influences of van Gogh, Gauguin, symbolist painters, and the group of French protomodernists known as the Nabis. Munch’s mystical visions of nature with feverish, bravura brushwork and bold color, succinctly underscore the artist’s position as a modernist leader and one of the foremost pioneers of expressionism.

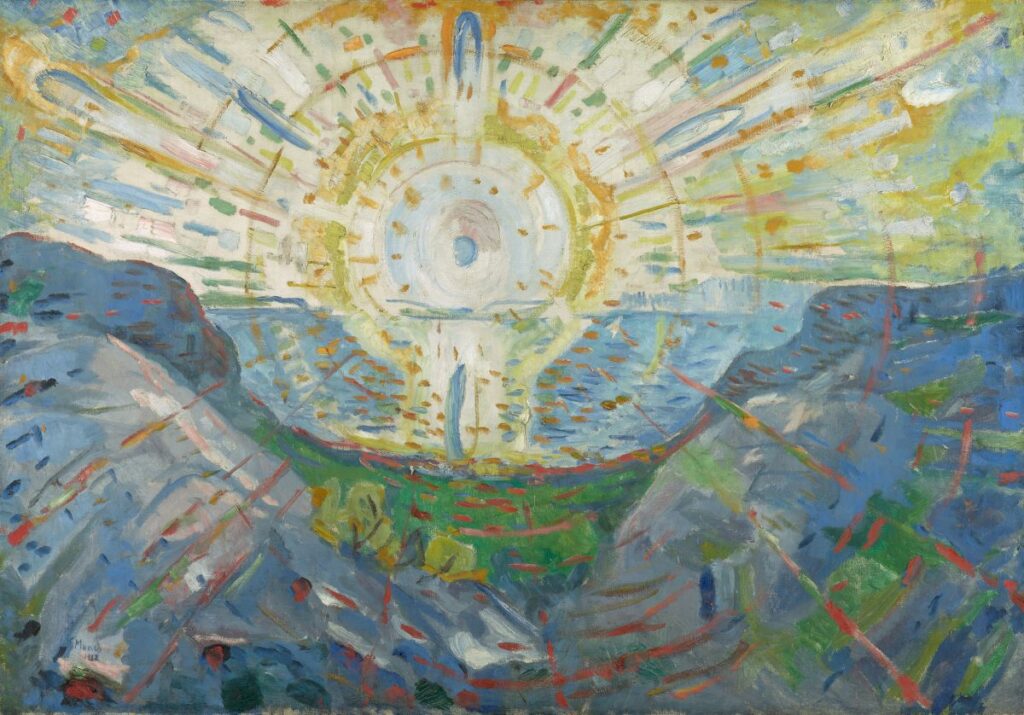

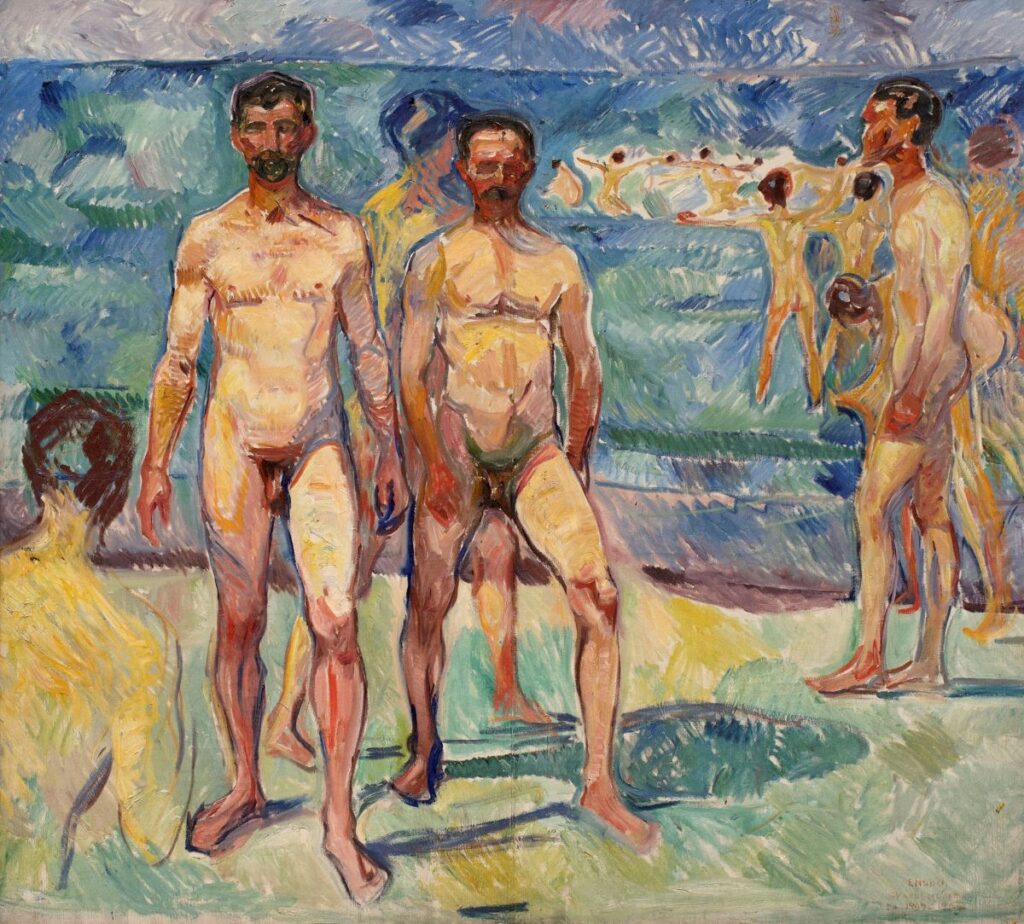

Thankfully, as in the Met exhibition, The Scream is represented here by a modest 1895 lithograph, allowing many other works to shine. Much more subtle, but equally effective, for example, are landscapes and seascapes inspired by the Oslo Fjord and the Baltic coast of Germany, a country where Munch resided for some years. The exhibition features many highlights from his long career, including The Storm (1893), in which a number of ghostly figures appear engaged in a mysterious nighttime ritual, and The Girls on the Bridge, showing a group of female figures seemingly in the midst of a physical and—in Munch’s view—a psychological transition. In Bathing Men; Middle Age, a large composition of nude male figures on a beach, Munch pays homage to those sun worshipers who seek a direct connection to nature—deliberately eschewing restrictive social conventions and invasive technology along with their clothing. The Sun, depicting a centralized glowing white orb with radiating bands of blue and gold, is surely a passionate paean to nature—its power to heal and replenish—as well as a cry for its preservation.

Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth • Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts • to October 15 • clarkart.edu