The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia uncovers and shares compelling stories about the diverse people and complex events that sparked America’s ongoing experiment in liberty, equality, and self-government. To that end it has recently launched a partnership with Ancestry.com, through which nearly two hundred rare documents bearing the names of Black and Native American soldiers who served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War are now accessible online free of charge. The documents form the Patriots of Color Archive, which the museum acquired in 2022 from a private collector, and which Ancestry digitized as part of its commitment to preserving history that is at risk of being forgotten.

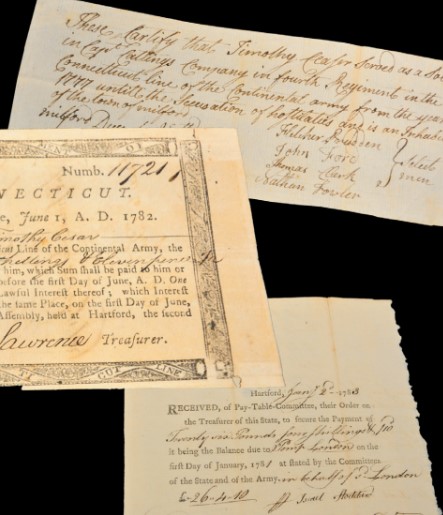

We asked Aimee Newell, the museum’s curator, to share some of the stories this rare trove has revealed. She writes: “The Museum of the American Revolution acquired the Patriots of Color Archive in order to continue to lift up stories that have often gone untold, as part of our conviction that inclusive history is the most accurate history. The archive comprises original muster rolls, pay vouchers, enlistment papers, discharge forms, and other documents, primarily from Connecticut and Rhode Island, assembled over two decades. Each document has a story to tell, helping us to learn more about the lives and experiences of these soldiers.

Several men named served in the First Rhode Island Regiment, which included two segregated companies of Black and Native American men. From a receipt dated June 12, 1779, tracking payments made by a Captain Thomas Cole to almost fifty soldiers of the regiment, we have been able to rediscover the lives of some of them. For example, one man, Benjamin Frank, served with the regiment in several battles and then deserted in 1780. When he reappeared in 1782, as Ben Frankham, he had switched sides, eventually leaving with the British at the end of the war and settling in Nova Scotia. Another soldier, Anthony Griffin fought at the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. On the way to Yorktown in 1781, as the regiment passed through Maryland, he was recognized by his former owner, who reclaimed him, returning him to bondage.

As an example of information about Native American soldiers, we have two documents relating to Jabez Pottage, a member of the Nipmuc tribe, who served in the Seventh Connecticut Regiment from 1777 to 1780. One is a certification of his service in the Continental Army, where he states that he is entitled to his ‘whole wages and allowances,’ just like other troops. The second is a pay receipt for his service totaling slightly over forty-eight pounds, showing that he was, indeed, paid just like other troops.”

To access the archive, visit Ancestry.com/AmericanRevolutionBlackandIndigenousSoldiers.

A perfect complement to the archive, in 2021 the museum commissioned the painting shown here, Brave Men as Ever Fought, from historical artist Don Troiani. The work’s title are the very words Philadelphia sailor, businessman, and abolitionist James Forten (whose distinguished family was the subject of a recent exhibition at the MAR) used to describe the Black and Native American troops members, in fact, of the First Rhode Island Regiment, who marched past the Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, in Philadelphia on September 2, 1781. Like so much that the Museum of the American Revolution does, this painting and the Patriots of Color Archive go a long way to telling the often-unfamiliar stories of free and enslaved people of African descent during the Revolutionary era.