Ever wonder how the Menil Collection sustains its reputation for unfettered curatorial magic and style-setting architectural choices? How it balances think-big Texas boldness with a brainy Gallic outlook inherited from oil-rich founders? Look no farther than its current exhibition, Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect, Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Lequeu show includes fifty highly detailed ink-and-watercolor drawings that expose the fantasies, both sexual and artistic, of a failed architect born in 1757. Which is to say, it’s a surprising choice for an institution that has long been a standard bearer for contemporary art.

Lequeu takes center stage at the Menil Drawing Institute, a Mies-meets-origami jewel box that is the latest addition to the tree-shaded Menil campus in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. Designed by the Los Angeles-based firm Johnston Marklee, this lofty thirty-thousand-square-foot pavilion seems especially suited to contemporary art—from the ten-foot-high drawings by Roni Horn that were shown there in 2019, to a forthcoming exhibit of Brice Marden abstractions. The Institute opened its doors in 2018 with a career-spanning look at Jasper Johns’s drawings, many of them from the Menil’s own holdings.

But Lequeu also belongs at the Menil, said Edouard Kopp, the Institute’s recently appointed chief curator. He put together the Houston display with colleague Kelly Montana, and will send it on to New York’s Morgan Library & Museum after the Texas show closes on January 5. Their exhibition pulls from an expansive Parisian show of 148 works co-organized by the Petit Palais and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

“We have a history with Lequeu,” Kopp said. “His work was first shown in Houston with support from the Menil Foundation in 1967—an exhibition that put him in context with his better known contemporaries, the visionary architects Etienne-Louis Boullée, and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.”

Fifty years ago, Lequeu’s work was still emerging from obscurity. His drawings had long been forgotten, bequeathed to the Bibliothèque nationale de France when the elderly artist, impoverished and ignored, couldn’t find buyers for his life’s work. More than eight hundred drawings went into the archives—the products of a solitary dreamer whose career as an architect had stalled when traditional patronage collapsed during the French Revolution.

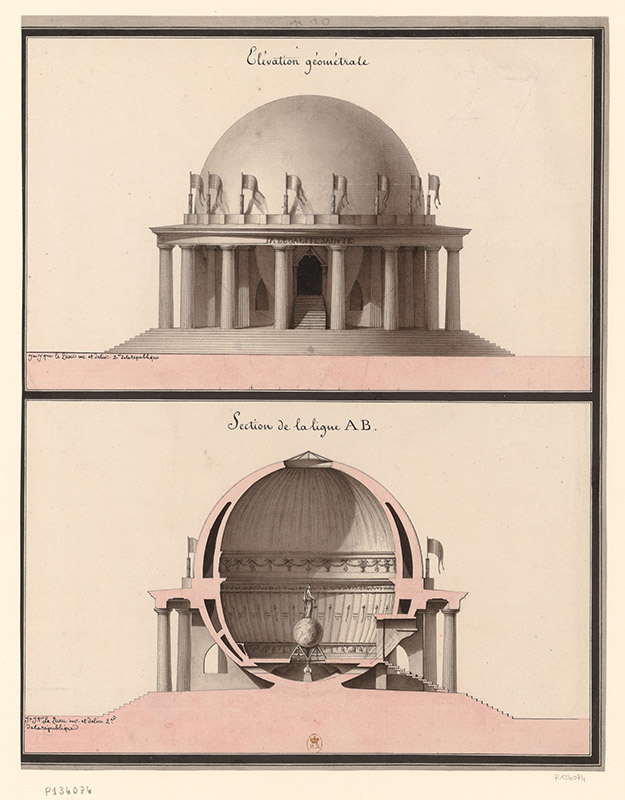

Lack of commissions didn’t keep Lequeu from responding to the architectural avant-garde of his era, however. His 1794 drawing Elevation and Cross-section of a Temple to Equality shows Lequeu’s fluent, individual response to the neoclassical sobriety of his early mentor, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, who designed the Panthéon in Paris. With such renderings, Lequeu also put himself in the visionary camp, alongside Boullée and Ledoux, whose monumental structures—both built and unbuilt—often seem like essays in solid geometry.

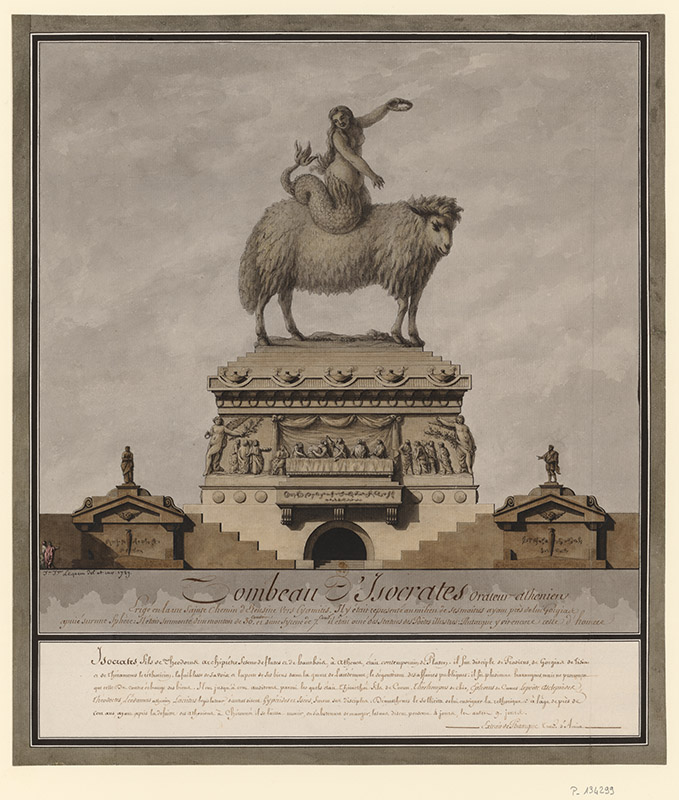

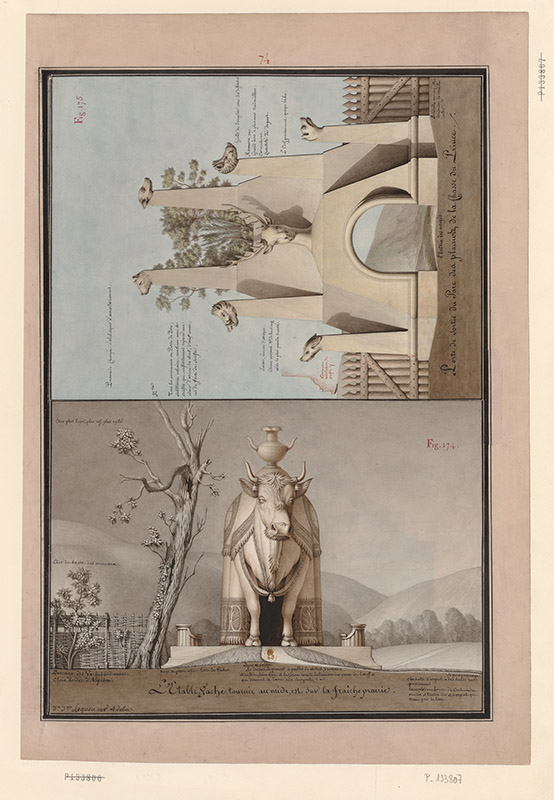

In these years, Lequeu embraced another architectural concept born in the eighteenth century: that the shape of a building should express its function. At the Menil, his version of parlante, or “speaking,” architecture takes many forms: a barn in the shape of a bull; a temple that pledges to unlock mysteries for those who pass through its keyhole-shaped portal.

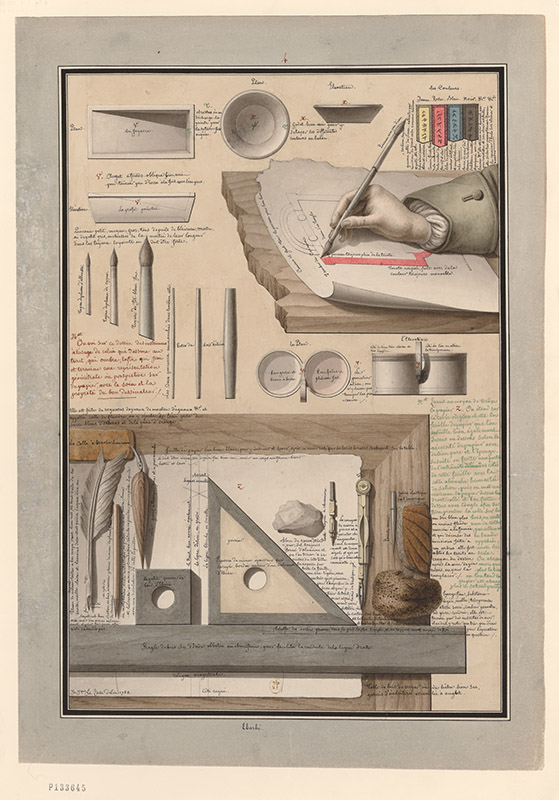

Much of Lequeu’s work puts him firmly within the Enlightenment tradition. Consider his precise, elegantly detailed drawing of The Draftsman’s Tools, which resembles a didactic illustration from Diderot’s Encyclopédie. For Kopp, this sheet also provides a perfect introduction to Lequeu’s oeuvre, one that “demonstrates his immaculate technique, and his ability to create a very clear mise-en-page. He is an architect, but this piece situates him in the realm of drawing—and that’s our focus here. We bring together curators, artists, collectors and the public to think about what drawing has been in the past and what it can be in the future.”

Lequeu kept drawing even as his hopes dimmed for an architectural career. What started as a public demonstration of skills and sensibility, became a venue for private reverie. The careful plans and elevations remained, but the projects became unbuildable—a 650-foot tomb atop a labyrinth; a temple to Ceres composed of draped garlands and blooms; a Cross Section of the Underground of a Gothic House with domed grottoes and burning crypts that might have made a dream home for de Sade.

Displayed in this context, Lequeu’s remarkable suite of self-portraits look a bit troubling, too. Ostensibly part of the rational, eighteenth-century study of physiognomy, these drawings seem to mirror the artist’s inner state and his anguished response to the upheavals of his era. Other works, including the portrait bust in Lequeu’s Frontispiece to the New Applied Manual of the Elementary Principles of Drawing, might prompt a visit to the Menil’s grand collection of surrealist works, especially those of Giorgio de Chirico.

Viewed through modern eyes, this long dead French architect can seem like a surrealist before-the-fact, perhaps even a candidate for psychoanalysis. It’s part of his appeal, even for viewers who dislike anachronisms.

What drove Lequeu? Ambition? A craftsman’s pride? A visionary’s need to express himself? All those elements come into play with Lequeu, but there’s something else, something insistent, that makes his work feel more immediate than most architectural drawings. It’s sex—a raw erotic undertow that flows through most images in the Menil show.

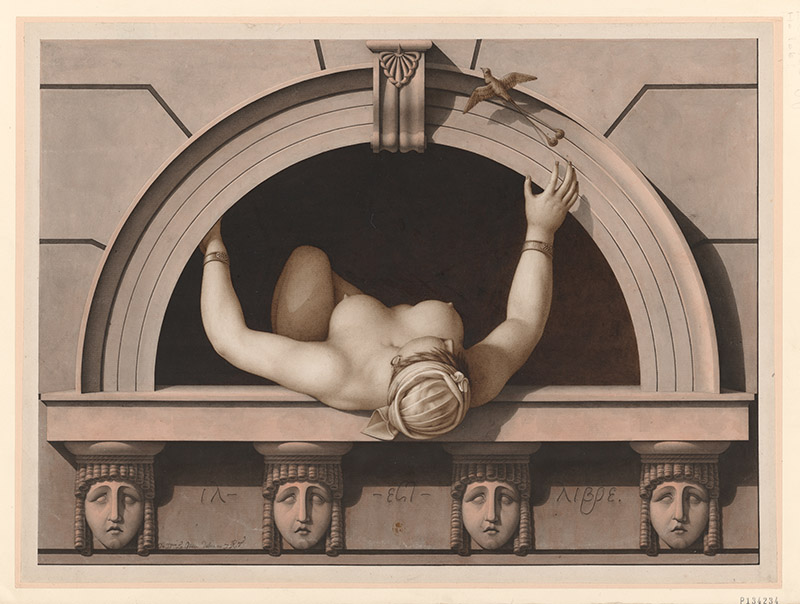

In Lequeu’s renderings, every keyhole entry, arched passage, grotto and cave invites Freudian interpretation. His statuary and caryatids often seem imprisoned by the composite orders of his designs: enslaved players from the fever dreams of a solitary draftsman.

In He is Free, from 1798–1799, a radically foreshortened nude sprawls in a shadowy archway, her figure as imposing as the weighty stone elements that surround her. It hardly matters whether she was Lequeu’s real life lover or an allegory for the profession that refused him. Dwelling in the closed world of Lequeu’s fantasies, she reminds one that every door and window can seem like an orifice, that the facades of buildings wear their passions as plainly as a human face.

New Orleans journalist CHRIS WADDINGTON is a regular contributor to The Magazine ANTIQUES and other national publications. His many awards include two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships for critical writing.