Spring going on Summer 2020: a season of no shows, no fairs, no fun at all for those of us who love the touch of antique objects and the visceral, not virtual, connection with the people who buy and sell them.

To browse, perhaps to handle . . . or maybe even hondle? Surely the day will come again. In the meantime we have gathered a few stories from the folk art field to bring back the joy. —EP

A Delightful Dual Discovery

It all started with a visit to the eastern Connecticut town of Canterbury. A grand eighteenth-century house was for sale and the real estate agent was a Liverant family friend interested in local history. The agent suggested that Arthur Liverant might enjoy seeing the house, a beautiful example of New England colonial architecture. A young collector friend happened to be in the shop when the call came, and Arthur invited him to come along. They arrived and were greeted by the agent, and introduced to the owner of the house and his family.

Despite years of neglect, the house was indeed impressive inside and out, retaining almost all of its sophisticated moldings and paneling. Trailed by a group of eight curious onlookers, Arthur entered the formal sitting room in the front of the house. Once there he found himself standing face to face with a small waist-length portrait of a young girl. He immediately knew by her delicately painted features and focused gaze that she was the work of the deaf-mute artist John Brewster Jr. of Hampton, Connecticut. “This is a valuable painting,” Arthur told the owner. He simply nodded in reply, waiting for Arthur to continue. “It was painted by John Brewster Jr. of Hampton and was painted about 1805. May I take it off the wall?”

The owner agreed and Arthur examined the painting by the light at a window. He was mesmerized by the image and the excellent original quality. He also noticed some light pencil inscriptions on the back of the stretchers. Arthur had to have it, or at least make a serious effort to get it. He pulled the agent aside and asked, “Is it ok if I make an offer on the painting?” The agent said, “Sure, go ahead.” Arthur turned to the owner and made his offer, leading with his best foot forward. The owner was a bit stunned by the size of the offer and simply replied, “Why?” Arthur explained that the rarity, condition, and freshness to the market all played a role in the significant value. The owner stood in silence for a long moment, then said, “I’ll have to think about it.” Filled with the mixture of excitement of the discovery and the disappointment of leaving the house empty-handed, Arthur headed back to the shop.

When he returned, he was beside himself. “You will not believe what I just found!” he said. “The most incredible Brewster portrait, she’s like the Mona Lisa!” But now came the hardest part: the waiting. And waiting. And a few more days of waiting. Finally, Arthur couldn’t wait any more and called the owner. But there was no reply. He left a message asking him to call, but no call back came. Eventually, the owner answered one of Arthur’s calls. Relieved to finally get him on the phone, Arthur asked if he had considered our offer. “I have,” said the owner, “and I’m going to put the painting in auction.” Arthur reacted with animation and determination, “You can’t do that!” he exclaimed, “You wouldn’t have known what that painting was or what it was worth if I didn’t tell you. It has been hanging on the wall of the house for the last five years while the house was on the market and nobody else knew what it was. I was honest with you, and we are paying you a fair price, please sell us the portrait.” The owner seemed determined to put the painting in auction, but Arthur continued, “At least let me and my associate come over and speak with you in person.” The owner tentatively agreed and Arthur loudly proclaimed, “Kevin, get in the car we’re going to Canterbury!”

Arthur and I just about flew over to the house. Soon we were standing in front of the remarkable portrait. Her sweet smile and character represented the best of John Brewster Jr.’s portraits. The owner was still inclined to auction the portrait, but Arthur was steadfast. He made an offer on the portrait that made my head spin. After a long pause the owner looked at Arthur and simply replied, “Ok, go ahead, you can buy the portrait.”

Relieved we had an agreement, Arthur showed me around the house. We made offers on a few other items and Arthur asked if we could see the attic. The owner agreed but added, “There’s nothing up there, it’s a mess and full of junk.” We said we didn’t mind a mess and climbed up the steep stairs. Among the dust and debris, propped up against the central chimney, were stacks of prints and paintings. All of a sudden I could hear Arthur proclaiming, “Oh, ooooh, ooooooh.”

To my amazement he was holding an exquisite early nineteenth-century silk-on-silk pictorial needlework featuring two young women playing musical instruments. It was in great condition and retained the original eglomise glass mat with the title Fair Musicians, and the initials “R. W.” Another sizable offer soon followed and the owner once again agreed. Arthur turned to me and said, “Kevin, why don’t you load the car while I write out a check?”

I gently took the fragile needlework and placed it on a bed of blankets in the back of the van. I gathered up the remaining items and took the portrait off the wall where it had hung for almost two hundred years. I thanked the owner and headed outside and sat in the passenger seat, staring at the face of this beautiful young lady from the past. As we headed home, I turned the portrait over to try and decipher the old pencil inscription on the stretchers. Among the scribbling was the name “Rebecca Warren” and the mysterious became the obvious. “That’s it! Rebecca Warren is R. W.! This is the girl that made the needlework!” In one exciting moment of clarity, these two beautiful pieces were once again linked. We advertised the pair in The Magazine ANTIQUES in May 2003 under the title, “Rebecca Warren and Her Needlework.” We recently had the joy of handling them for a second time, proudly presenting them at the Winter Antiques Show in January 2018.

—Kevin Tulimieri, Nathan Liverant and Son, Colchester, Connecticut

Expecting the Unexpected

One of the things my husband, Jimmy, and I love about the antiques business is the joy of anticipation, the sense that every day may be Christmas with a great treasure to be found. Let me take a special day in 1978 as an example. We were staying in Scarsdale, New York, with my family and traveling around the area with fellow dealers who suddenly made what I thought was a bizarre suggestion: “Let’s call Tony Sposato to see if we can visit him.”

I could not have been more surprised. “Tony Sposato? Do you mean the fellow who owns the gas station in White Plains?” I asked. Yes, they meant that Tony Sposato, the handy fellow who had fixed my family’s cars since I was a toddler. We went to Tony’s garage for help as religiously as some families went to church, and my mother even sewed clothes for his little granddaughter who was blind. I thought back and did recall that Tony’s tiny office at the station was filled with wall clocks so maybe he was indeed a collector. Still, I was doubtful.

We called and were invited to his house, arriving with no expectations on my part. And, yes, Tony was indeed a collector with every inch of every room filled with his finds, mostly formal American antiques but really nothing that held our interest until something suddenly stopped us. There amidst the crush of highboys and lowboys, tea tables and tall clocks was a hidden luminous jewel, a 1792 Pennsylvania dower chest, its terse geometry suffused with color, with lyrical motifs, with every iconic image its Pennsylvania German maker John Bieber could incorporate into his masterpiece. Jim literally fell to his knees.

When he recovered and offered to buy it, Tony reached into his pocket and brandished a large wad of bills. “I don’t need the money,” he said. That would have been that but for Tony’s affection for my family. He promised that if he were ever ready to sell the dower chest, he would sell it to us.

Jimmy does not give up easily on any front, ever. Each year on my birthday he called to see if Tony was ready. The answer was no and no and no. But then late one night Tony’s son called to say his father had died unexpectedly and he wanted to sell us the chest so his mother could buy a condo in Florida.

We drove up from Philadelphia to retrieve our treasure. We knew we had something of great value and we hoped to interest our family in helping us keep it for future generations. They remained unconvinced. We then called Bea Garvan, curator of American decorative arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “If it is the chest I think it is,” she said, “we will take it.” And they did. No longer ours, the chest lives on, the subject of scholarly articles and appreciative visitors, but also a glorious reminder to us that a life in the antiques business is one of adventure, discovery, and passionate people with whom we are privileged to share the journey.

—Nancy Glazer, James and Nancy Glazer American Antiques, Bailey Island, Maine

Chance Encounter

Most of our great finds have come to us from colleagues willing to share information, and many of those finds have required a great deal of time and patience in pursuit—sometimes even across generations. But one of our most exciting discoveries was the result of a single encounter with a total stranger. It was Christmas Day 1984. I had reluctantly agreed to go to a holiday party at my family’s request. The hosts were my sister’s friends and completely unknown to me.

As things were winding down, I sat alone in front of the fireplace and a man joined me. He introduced himself as Jim and said he worked in the raincoat business. I told him I was an antiques dealer who specialized in Americana. This piqued Jim’s interest. He began telling me about an antique table in his attic painted long ago by a distant aunt from Amherst, Massachusetts. He said he didn’t like the table and was considering cutting off its feet to make it into a coffee table. Needless to say, I told him that was a very bad idea. We agreed that I would take a look at the table the next day. My mother, Peggy—a keen judge of both antiques and people—came with me.

Our first view of the table took place in Jim’s freezing attic, where it had been disassembled with its top facing a wall, not an encouraging sight. But when the top was turned around, everything changed. We moved the whole piece to the warmth of the living room and set the top on the base. We were unprepared for the breathtaking piece in front of us. We had expected little more than an academy-painted sewing stand. Instead, we had unearthed the largest piece of schoolgirl-decorated furniture we had ever seen—an Empire-style maple center table covered with exuberant watercolor and ink decoration that included a still life on the top and cornucopias on the scrolled feet. It was signed and dated on the column: “Amherst, July 9, 1841 Sarah D. Kellogg.” The condition of the table was outstanding; its only flaw was a missing piece of quarter-round molding at the base of the column.

Jim seemed amused as we crawled around examining the table. When finished, we explained the genre of schoolgirl art to him and the importance of this particular table. We told him that we loved the table and presented him with a substantial five-figure offer. He was shocked. After regaining his composure, Jim asked us, “What should I do?” My mother suggested that he approach it the way he would if he were selling a house. She advised him to have the table independently assessed by three others: an appraiser, a dealer, and an auctioneer. Then, if our offer was best, he should sell it to us. Exactly one month to the day later, Jim accepted our offer, and the table ended up paying for an addition to his house with a new kitchen. We sold the table in 1985 to a private collector who donated it to the American Folk Art Museum in 2005.

—David Schorsch, David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles

American Antiques, Woodbury, Connecticut

A Portrait of a Man of Small Stature and Immeasurable Nobility

That Saturday morning in August 1977 began as most Saturdays did when antiquing, our newly chosen vocation, sent us down the Old York Road to Brown Brothers Auction Gallery in Buckingham, Pennsylvania, to preview the Saturday offerings. This was a time before smart phones, Google, and websites, a time when being in the right place at the right time had a different kind of urgency. And it was a day that would change our lives.

My business partner, Ed Hild, and I had decided to preview Brown’s early so I could get back to the shop in New Hope we’d opened the year before, and he could stay on, perhaps to buy something that would return a profit. Instead of the usual mundane household offerings and the occasional antique, we were greeted with the contents of a barn left behind by a family when they moved to England in the 1920s. It was a time capsule of objects of a kind we had not yet seen at that early point in our careers: eighteenth-century Philadelphia Windsor chairs, a settee of the period, and other early furniture, along with a small Civil War cannon with its original gray-painted wagon holding several cannon balls.

The other thing that caught our attention was the presence of all the “Big Boys,” the established dealers from Philadelphia and neighboring counties, and of several local collectors. We knew we’d be unlikely to compete with them, but Ed remained behind and I headed back to open shop. After losing the cannon to a $700 bid, Ed went outside to inspect the lesser offerings relegated to a shed. Sorting through a box of picture frames, he noticed that one contained what appeared to be a painting on a wood panel. Wetting his thumb, he rubbed off a bit of dirt and saw two tiny piercing eyes staring through the grime. He quickly returned the framed piece to the box and walked away nonchalantly.

Eventually, the auctioneer made his way to the shed, and when the box of frames was offered, Ed bought it for four dollars. Before he could retrieve his purchase, another bidder asked to buy the frames. Ed sold them for three dollars, retaining the one holding the painting.

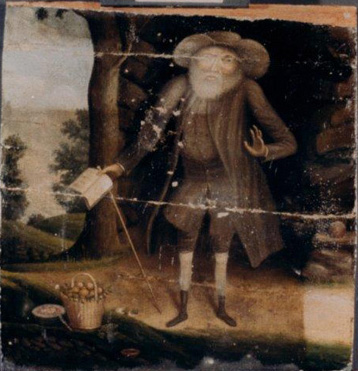

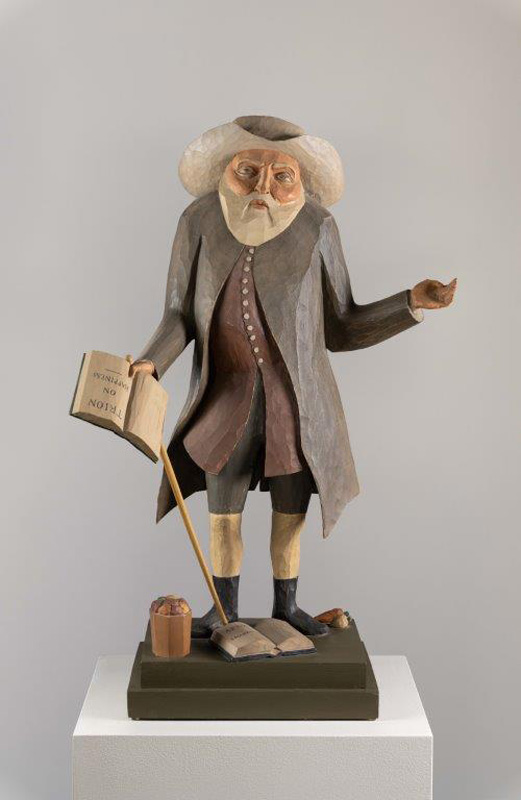

Back at the shop we carefully brushed the thick coat of dirt from the small picture to uncover the figure of an elderly bearded man in a waistcoat and Quaker hat. He was holding a cane and book and standing in a landscape. Clearly, this was an early painting, probably eighteenth century, but was it American and by whom? Its condition attested to years in a barn: a strip was missing from the top of the panel; there was a horizontal crack in the middle and numerous areas of flaking paint; and a warp prevented it from sitting properly in the frame. But the figure was captivating. On turning it over we discovered a hand-printed inscription, “Benjamin Lay.”

Who was Benjamin Lay? The artist, no doubt. We inquired among collectors and dealers we knew; we checked the library but no artist by that name could be found. Then a friend suggested we consult Winterthur, the American decorative arts museum in Delaware, and so we placed a call. Ed introduced himself to the woman who answered and said he needed information on an artist by the name of Benjamin Lay. “Benjamin Lay is not an artist,” she replied, “but we have an engraving of him by Dawkins.” Soon after, we were sent a copy of “Henry Dawkins and the Quaker Comet,” an article by Wilford P. Cole published in Winterthur Portfolio 4 (1978), and discovered the amazing story of the little man behind the dirt. Benjamin Lay was an English-born Quaker, a 4-foot, 7-inch hunchback dwarf married to Sarah (also of small size and similar physical condition), who came to Philadelphia in 1732 by way of Barbados. Credited with being one of the first abolitionists in the colonies, Lay chastised the prosperous slave-owning Quakers of the city while also influencing and making friends with such prominent figures as Benjamin Franklin, who published Lay’s three hundred–page polemic on slavery. A man of considerable intelligence and knowledge, he lived a modest vegetarian life with his wife six miles north of the city on the Old York Road, where he used an excavated cave for meditation and reading from his extensive library. Much has been written about this unique and accomplished figure, most recently Marcus Rediker’s The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist (2017).

We discovered something else from the Winterthur article: a letter from Benjamin Franklin in which he wrote to his wife Deborah from London in 1758: “I wonder how you came by Ben. Lay’s Picture.” We learned also that the artist was William Williams, an Englishman active in Philadelphia in the mid-eighteenth century and credited with inspiring the young Benjamin West to become a painter. All discussions of the Dawkins engraving, the engraver, and Williams referred to the original painting as “lost.” And here it was, the painting that Benjamin Franklin may have commissioned from William Williams of his radical friend Benjamin Lay. And it was ours. But we had to be certain, so we phoned Winterthur, and, with our filthy, broken, warped and flaking prize, set off to Delaware.

We were greeted warmly and invited on a private tour of the museum while the painting was whisked away to the conservation laboratory. Eventually, we were invited to the lab, where a curator pronounced it authentic and indeed the long-lost painting from which the Dawkins engraving had been taken. Moreover, the museum was interested in acquiring it. We admitted we did not yet have a price in mind, but we promised Winterthur first refusal, even though we were disappointed to learn that the museum would not go beyond four figures.

Given the compromised condition of the work, we decided to leave it in the hands of Winterthur conservators Joyce Hill Stoner and Mervin Martin while we considered our options for a potential sale. On our ride back to New Hope we were giddy with disbelief at our good fortune. Although there was no way we were going to part with this American treasure for four figures, we had no idea how to price and market it. Thus began an important period in our early education.

If Winterthur was interested, perhaps other museums would be, so we sent a letter to the curator of American art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and received a positive, if cautious, reply. But we still did not know how to assign a price. Eventually we decided to go public with our “find” in the hope of generating more interest. The local papers all jumped on the story with banner headlines about the one-dollar purchase netting a “lost” treasure worth a small fortune. The first article, written by Lita Solis-Cohen and published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, estimated the value at $65,000—a price we had never mentioned even though we might secretly have wished for it.

In the spring of 1978, honoring our commitment to the right of first refusal, we offered our treasure to Winterthur at a five-figure price. They declined and we retrieved the painting, now wonderfully restored. A call to the Philadelphia Museum was similarly disappointing, especially given the painting’s historic importance to the city.

So we were off to New York and Sotheby’s, where the head of the American paintings department told us that the painting was of no interest for his upcoming sale. We might have been young but we weren’t stupid; it was apparent that this “expert” had not bothered to read the documenting evidence. From there we visited the dealer George Schoellkopf at his gallery on Madison Avenue. George was interested in the painting and offered to take it on consignment for a net of $10,000. We headed back to Pennsylvania, painting in hand.

Not long after our New York adventure we came across a 1937 article in The Magazine ANTIQUES discussing the Dawkins engraving and the missing painting. I calledthe magazine, and told the woman who answered that I had a story she might be interested in. Indeed she was! The January 1979 issue of the magazine described our find in “Collectors’ notes,” and it was there that we learned for the first time that the painting had been mentioned in an 1810 list of the artist’s works, transcribed from the original, as “A.D. 1750—Pictures painted at Philadelphia amongst 100—the owner of each is specified—is a ‘Small Portrait of Benjamin Lay for Dr. Benjamin Franklin.’” It had been commissioned by Franklin after all. And its whereabouts from 1759 until 1977 had been a mystery.

Almost as soon as the magazine article appeared, we received a phone call from Monroe Fabian on behalf of the National Portrait Gallery, asking if the painting was available and at what price. Remembering the two previous museum rejections, I hesitated but stuck to our price. There was no hesitation on his end; his only question was how soon could they pick it up for examination and presentation to the acquisitions committee. Within a month the painting was in its new home at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

So how did we arrive at a price? There were no auction records to determine value, and, anyway, how do you put a price on such a historically significant provenance? We discussed what we hoped to do with the proceeds and let that guide us: we wanted to buy a property with a house and an outbuilding for a shop. We also wanted to purchase inventory of the caliber we had come to appreciate.

Within a few months we met our first goal when a place with a carriage house on Route 202, Bucks County’s “antiques trail,” became available. When a local collector and friend, forty years our senior, who had a house full of wonderful Americana asked somewhat archly where we planned to get our inventory, I replied, “From you.” And, indeed, we did. But that is another story.

—Patrick Bell, Olde Hope Antiques, New Hope, Pennsylvania

So Wrong, Yet So Right

Forty years ago my path to discovering great things meant getting up at 3:30 am and driving to a little antiques or art fair in a school gymnasium, cow pasture, or somewhere else equally remote. As I got busier, I learned to depend on a network of other eyes, belonging to dealers known as “pickers.” These pickers might call several times a day, or send numerous photographs to my gallery. Most of the time their tips did not point me to what I was always hoping to find, that golden nugget.

One day I received a call from a dealer friend who’d received something from a Pennsylvania picker he thought was right up my alley: a painting of a nude standing on a black-and-white checkerboard floor that had, he said, a “Morris Hirshfield” look to it. I went to his place to see it. The painting was push-pinned onto his wall, not yet stretched, framed, or cleaned. I loved it. I wanted it. After all, how expensive could it be? Quite expensive it turned out. I loved the painting but hated the price. I said I would think about it. After a long night fluctuating between yes and no, I decided the painting was financially out of reach. So that was that . . . at least for the time being.

Fast-forward three years. I got a call from a close friend, Cynthia Beneduce, who had a shop on Bleecker Street in Manhattan. She had just returned from a small antiques show in Pennsylvania where she bought a painting she thought I’d like. She described it as an almost life-sized nude standing on a slanted black-and-white checkerboard floor and asked if I’d like to be the first to see it. I went right down to Bleecker Street and, yes, it was the same painting—now stretched and cleaned but still unframed. I did not tell her my history with it. I simply asked quite casually what she would like for it, and as her price was a fraction of the earlier quote, I bought it without further discussion. It has graced my walls for more than twenty years now and remains one of my favorites.

The painting was in all probability commissioned for a bar or a men’s club. Extensive research on the artist, whose dated signature can be found at the work’s lower right corner—“J.V. Fuentes. Boston 1893.”—turned up nothing. I can only assume that Fuentes was a self-taught artist who was trying to emulate classic iconography, and, in a sincere attempt to get it all “right,” got it all “wrong.” He included architectural and decorative elements such as crimson drapery and a heavily ornamented column to frame his composition, but the perspective and proportions are technically wrong: the woman looks like she is sliding down the floor at a forty-five-degree angle. It hangs on my wall, living proof that even when you get things objectively wrong, you can instinctively get them right.

—Frank Maresca. Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York City

An Exceedingly Sweet Find

I first became aware of this maple burl sugar bowl in early August 2001. It was listed on eBay, and because the auction would end during the distractions of Antiques Week in New Hampshire, I felt it had a good chance of flying under the radar. It didn’t.

I was on a dial-up connection, and my hands were sweating over the keyboard. Bidding and continuously refreshing the page, at the close of the auction I looked to see if I was the high bidder—I was. The package arrived by FedEx. I opened the box and was immediately overcome with immense satisfaction and giddy delight. The bowl was everything that I hoped it would be. The form, figure, and feel were sublime. It was su-burl-ative!

From the form, reminiscent of Chinese export porcelain, I knew that it was from the eighteenth century, circa 1760 to 1780, and likely of New England origin. The figure of the wood led me to conclude that it was likely maple burl. The shellac appeared to be of the period.

The sellers told me they had purchased it as a deaccession from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco shortly after the 1989 earthquake; there was no additional information given. It did, however, have an old label on the bottom, which read, “Property of W.G. Blunt. Deposited as a loan.” In blue ink, “ADEC” and “272.4.” This led me to wonder who “W.G. Blunt” was, and why this early New England bowl was in a San Francisco institution.

I soon learned that on November 22, 1902, William Greenleaf Blunt stood on the doorstep of the de Young Museum, in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, and when the door to the museum opened a curator greeted him. As Blunt told the story of the bowl, the curator listened and entered details into the museum’s catalogue books. The ledgers were laid out with specific headers and ruled boxes: Museum Number, Character of Object, Received From, When Received, Remarks, etc. The story seemed to have more details than the ledger would allow, so only the essentials were recorded. As the door closed and William left the museum, so did the story of the sugar bowl. Its history would be lost for another hundred years.

Over the next two and a half years of extensive research, I was able to determine that the maple burl sugar bowl deposited into the de Young Museum in 1902 by William Greenleaf Blunt was part of a family legacy. It had been the sugar bowl of his great-grandparents, Matthew and Elizabeth Patten of Bedford, New Hampshire.

Remarkably, Matthew Patten’s daybooks exist and are published. His books from 1754 to 1788 give one of the best accounts of eighteenth-century daily life in a small New England town. Patten was a joiner and writes of turning burl bowls and even makes one entry that possibly pertains to this same bowl. On March 13, 1781, he wrote: “I paid Mrs. Chandler a pound of Coffee I borrowed from her a fortnight or three weeks ago and I borrowed the full of our Shugar dish of shugar from her.”

Elizabeth and Matthew Patten were pioneers of the American East. And their granddaughter Susan Patten, along with her husband, Phineas Underwood Blunt, and their children, were pioneers of the American West. Susan’s son, William Greenleaf Blunt, recognized this and was proud of his family’s history and donated a humble heirloom, a maple burl sugar bowl, to his local museum as a testament to their stake in settling this country.

Of the hundreds and thousands of American burl and domestic treen objects that I have handled over the years, this is the only one with a provenance of more than two centuries, and that possibly ties it to its maker.

—Steven S. Powers, antiques dealer, Brooklyn, New York

The Girl in Red (and me)

I began collecting in the late 1960s. Soon thereafter, one of the San Francisco museums hosted an exhibition of American folk art. Though I had a decent acquaintance with the field by then, never had I seen anything quite so stunning as the painting suddenly before me, an intense little girl with a red necklace in four strands, a blazing red dress, a luminescent white cat on her lap, and a small dog peeking out behind her feet. It was the Ammi Phillips girl now known (somewhat stiffly) as Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog. I looked to see who owned her; “Private Collection,” the label read, and my blood ran a little faster. Maybe someday I could find out whose collection it was. Even so, I hardly dared hope ever to own her (not that “owning” an artwork is how I think of it—it’s more like being a custodian or a curator).

A few years passed, and one day the dealer James Abbe, from whom I’d purchased Erastus Salisbury Field’s wonderful Israelites Crossing the Red Sea, was in the Bay Area and came to visit. Conversation was casual in the cocktail-time sort of way, but on a sudden impulse, I said, “Do you happen to know who owns the Girl in Red?” Pause. “Yes,” said Jimmy, “My sister-in-law.” Recovering from the shock, I said, “Well, if she should ever want to sell . . .”

Another year or two later I heard from Abbe again. His sister-in-law had at last decided to sell. The girl was mine if I wanted to meet the price, which was a lot more than I’d ever paid for a painting. But how could I possibly resist? As I learned the story later, Jimmy’s sister-in-law had met a dealer carrying the painting down Fifth Avenue—and bought it on the spot. Now, miraculously, I could have her.

When she arrived in California, she beamed down from the wall of a dining alcove of my house. Not long after, I loaned her to the Whitney Museum for a show and, after that, to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Colonial Williamsburg. Much as I delighted in her company, I had realized that a lightly guarded house in a semirural area of the San Francisco peninsula was not the safest lodging for her. I didn’t want to go down in the story of American folk art as the person from whom she’d been stolen, or who’d let her go up in flames, or otherwise get lost. I contacted Abbe once more. In turn, he arranged a sale to Ralph Esmerian, on condition that the painting go eventually to the American Folk Art Museum, of which Ralph was a devoted and tireless patron. Soon it hung conspicuously there, the first thing you saw as you entered the powerful, if controversial, building by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien (later demolished by MOMA in an act of wanton destruction).

Since then, the girl has appeared on a postage stamp. She is prominent in the Wikipedia entry for Ammi Phillips, which includes several accolades for the painting from the art-critical establishment. She has found herself side-by-side with Mark Rothko in a brilliant show organized at AFAM by Stacy Hollander. She is even the subject of a book for children, a fictional account of how she came to be painted. She has become, in a word often used too lightly but perfectly appropriate here, iconic. And, once upon a time, she hung on my wall.

How lucky I was.

—Bliss Carnochan, Lyman Professor of the Humanities

emeritus at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California

A Sleigh Ride There and Back

My story begins in July of 1977 in Hallowell, Maine, my hometown, where antiques shops line Water Street. My parents, Butch and Betty Berdan, owned one of them. My family lived and breathed antiques. While my father knocked on doors in search of great discoveries and my mother kept shop, I spent my days as an eleven-year-old on Water Street helping out in various ways, but also talking to my “extended family” of antiques dealers. I remember many of them fondly—my grandmother Marjorie McLean, Bob and Marianne Schneider, and especially Timmy Plumer, who always had a poker game going in his “office.” It was a joyous and optimistic time in the business: in the wake of the bicentennial people were eager to furnish their homes with a part of the American past, and Hallowell, known as Maine’s antiques mecca, drew them from across the country.

I was sweeping a dusty sidewalk on that late July morning when a Town and Country station wagon pulled up and a middle-aged woman leaned out to speak to me. “Young man I have something to sell,” she said. “Do you think these people might be interested?” I told her I would get my mother and that I was sure she’d like to see what the woman had. I fetched my mother and we went out to meet the motorist, who had a mysterious object wrapped in a moth-eaten army blanket. She told us she was from Bangor, the descendant of a whaling family, and she had, she said, a weathervane that had belonged to her family for years. She unwrapped it, and I remember feeling the incredible excitement of seeing a classic depiction of a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” I could tell my mother was excited too.

They agreed on a price and my mother quickly put the weathervane away as a surprise for my father’s fortieth birthday the following week. We were especially excited because my dad loved whaling folk art and anything with a Maine provenance.

On August 5 we threw a surprise birthday party for my father at a local Greek restaurant with our family and our entire Hallowell family of fellow dealers in attendance. It was a great party, and as I look back, I am so grateful to my mother for doing this. My father would be gone in less than ten years. He was overwhelmed by the gift and it held a place of honor in our home for more than twenty years, a wonderful reminder of a special day for a remarkable man.

In 1998 my mom, Betty Berdan-Newsom, sold their collection. The weathervane disappeared and I assumed I would never see it again. Over the years I’d encounter other versions of the Nantucket sleigh ride, but they never came close to the original, leaving me to wonder what happened to the beautiful object that marked a special day in my family’s life.

But then, fifteen years later, the whale reappeared at a James D. Julia Auction. I was astonished. Knowing how much the weathervane meant to me, my husband and business partner, Tom Jewett, bought it as a Christmas surprise. It came home to us. The Nantucket sleigh ride is among my most cherished possessions, both for the memories it holds and the dynamic creativity of its unknown maker. It has twice been a gift given out of love, reminding me that the things we prize often have deeper meanings and more poignant histories than as simple merchandise. Surely that is one of the things that makes this business special, a privilege even.

We are only caretakers of the weathervane and I hope one day someone will hold on to and love it as much as Tom and I do.

—Charles Berdan, Jewett-Berdan Antiques, Newcastle, Maine