Fig. 2. Grupp VI, Evolutionen, nr 15 [Group VI, Evolution, No. 15], 1908. Oil on canvas, 39 by 51 1 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are from the collection of the Hilma af Klint Foundation, Stockholm; photography by Albin Dahlström, Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Fig. 1. Photograph of Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) in her studio, photographer unknown, c. 1895. Wikimedia Commons.

When the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944, a few days shy of her eighty-second birthday, she left more than twelve hundred paintings and drawings, along with some 124 notebooks, sketch pads, and book manuscripts containing approximately twenty-six thousand pages of written notes and reflections. On these pages, af Klint documents her activities and her influences; records her motivations, her artistic processes, and her ambitions; inventories her symbolism in an alphabetical lexicon, and catalogues her artworks in black-and-white photographs and watercolor reproductions annotated with instructions for their display. Af Klint assesses and analyzes her creations both at the time of each work’s production and retrospectively, as throughout her life she continued exploring and trying to understand the meaning of the images she painted and the spiritual context of human existence.

Classically trained at Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, af Klint sold and exhibited portraits, naturalistic landscapes, and botanical illustrations throughout her life (Fig. 4). But she showed the strikingly original abstract works she began painting in 1906 to relatively few people. When she did, she often was met with disappointing reactions, and she was never successful in placing her artworks in the contexts she had imagined for them. Profoundly aware of how innovative her highly imaginative abstract works were, however, af Klint became convinced that her paintings’ full meaning could not yet be completely understood, and that her true audience simply did not yet exist.

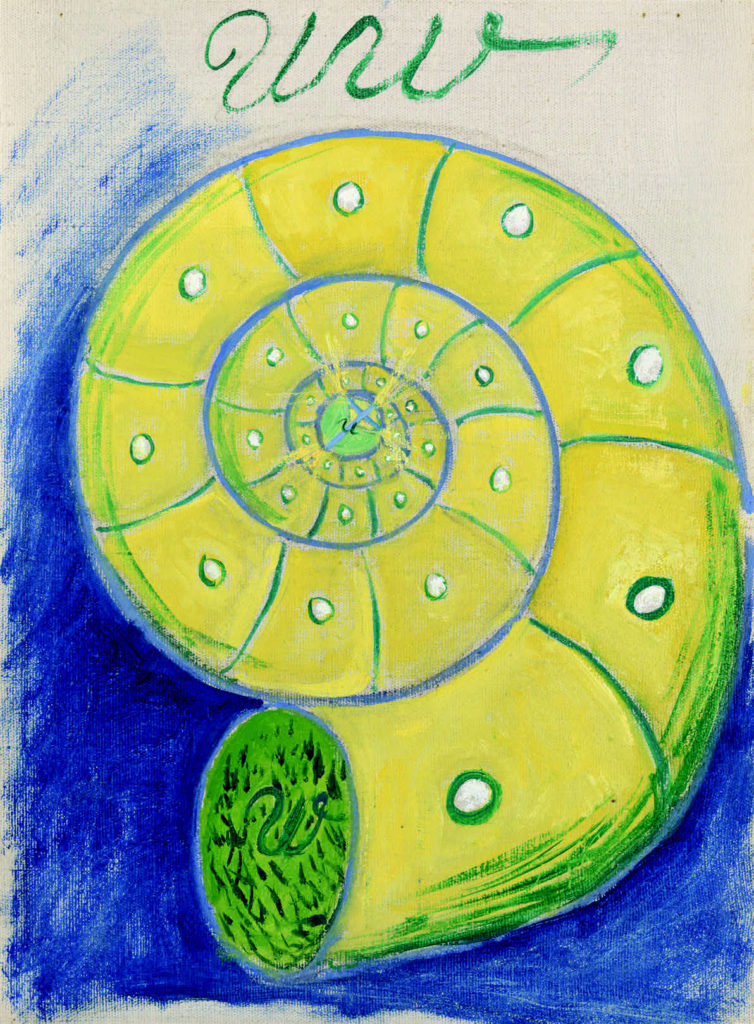

Fig. 3. Grupp 1, Urkaos, nr 16 [Group I, Primordial Chaos, No. 16], 1906–1907. Oil on canvas, 20 7 by 14 ½ inches.

Like many of her contemporaries, af Klint was influenced by the spiritual movements of her era, including theosophy and anthroposophy, and, in her work, strove through various means to visualize concepts beyond what the eye can see. From 1896 to 1915, af Klint worked under the guidance of higher beings with whom she communicated through a medium. Setting aside conscious thought, she developed original, abstract imagery and forms through a practice of automatic drawing that she began during séances with a group of four other female artists who together called themselves De Fem, or The Five.

Fig. 4. Untitled, 1890s. Watercolor and ink on paper, 6 by 5 inches.

From 1906 to 1915, af Klint completed a spiritual “commission” of 193 paintings and works on paper intended for a visionary but as-yet unrealized sanctuary—an ambitious cycle comprised of multiple smaller series in various mediums and formats that are collectively known as The Paintings for the Temple. Among these, the paintings that comprise a group she called “The Ten Largest” are groundbreaking not only in their abstraction, but in their scale, each ten to eleven feet high (Fig. 8). Empowered by the completion of The Paintings for the Temple, af Klint ceased to employ spiritualism to create her paintings and instead worked consciously for the remainder of her life.

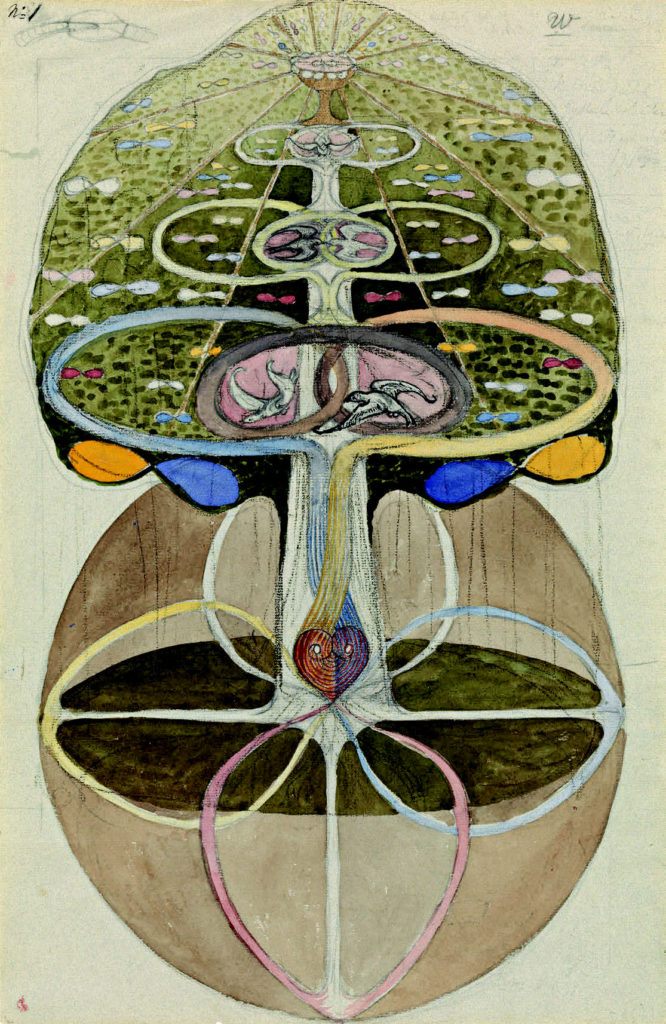

Fig. 5. Kunskapens träd, nr 1 [Tree of Knowledge, No. 1], 1913. Watercolor, gouache, graphite, metallic paint, and ink on paper, 18 by 11 ½ inches.

Though af Klint’s works on paper and on canvas contain representational elements—such as imagery derived from plant life and other organic forms—over the course of her career these biomorphic shapes and symbols grew more simplified and geometric, more fully abstract. Mixed with letters and invented words, this multifaceted imagery creates a vocabulary that eludes straightforward interpreta.tions, and instead vibrates with complex and fluc.tuating meanings. Af Klint’s idiosyncratic works explore syncretic modes of spirituality and the great world religions, the quest for knowledge in Arthurian legends, Goethean color theory, the Darwinian concept of evolution, and subatomic physics. Throughout all of this, af Klint strives to turn away from the visible world, away from two-dimensional illusionism and three-dimensional reality, to explore unknown dimensions of existence.

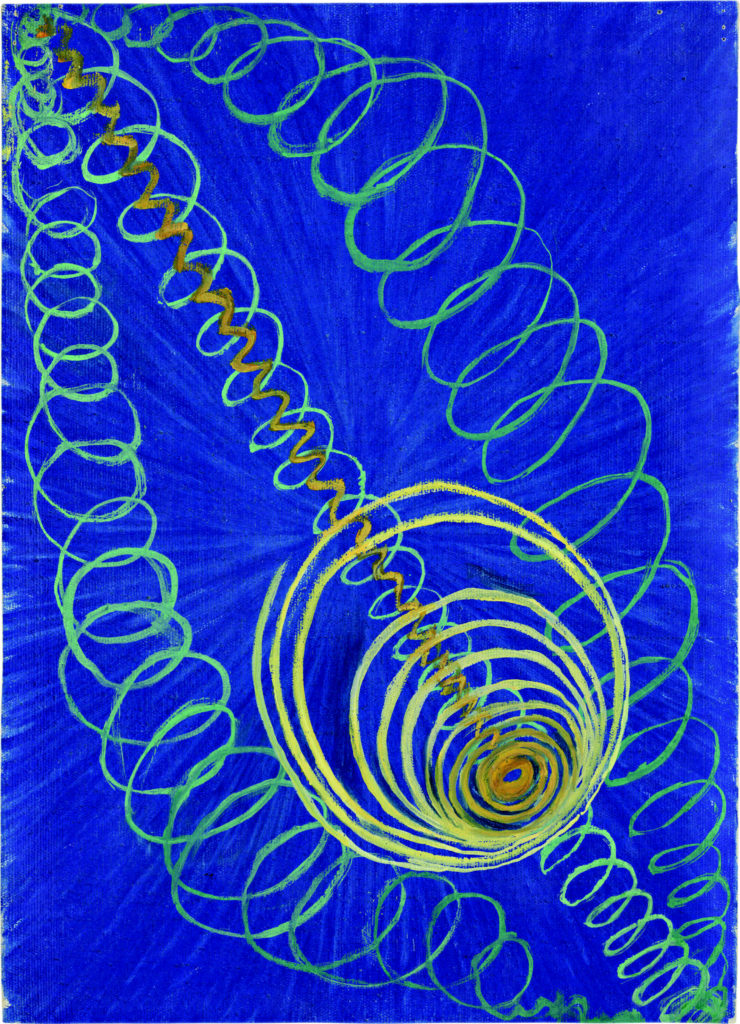

Fig. 6. Grupp I, Urkaos, nr 5 [Group I, Primordial Chaos, No. 5], 1906–1907.Oil on canvas, 20 7 by 14 ½ inches.

Counting upon future interest in and receptivity to her work, in the last decade or so of her life, af Klint painstakingly edited and ordered the notebooks in an effort to make her work accessible to later generations. On the first page of nearly every notebook, she marked the characters + x. These symbols, she explains in a 1932 inscription, indicate her wish that any works carrying that sign should not be viewed until twenty years after her death.

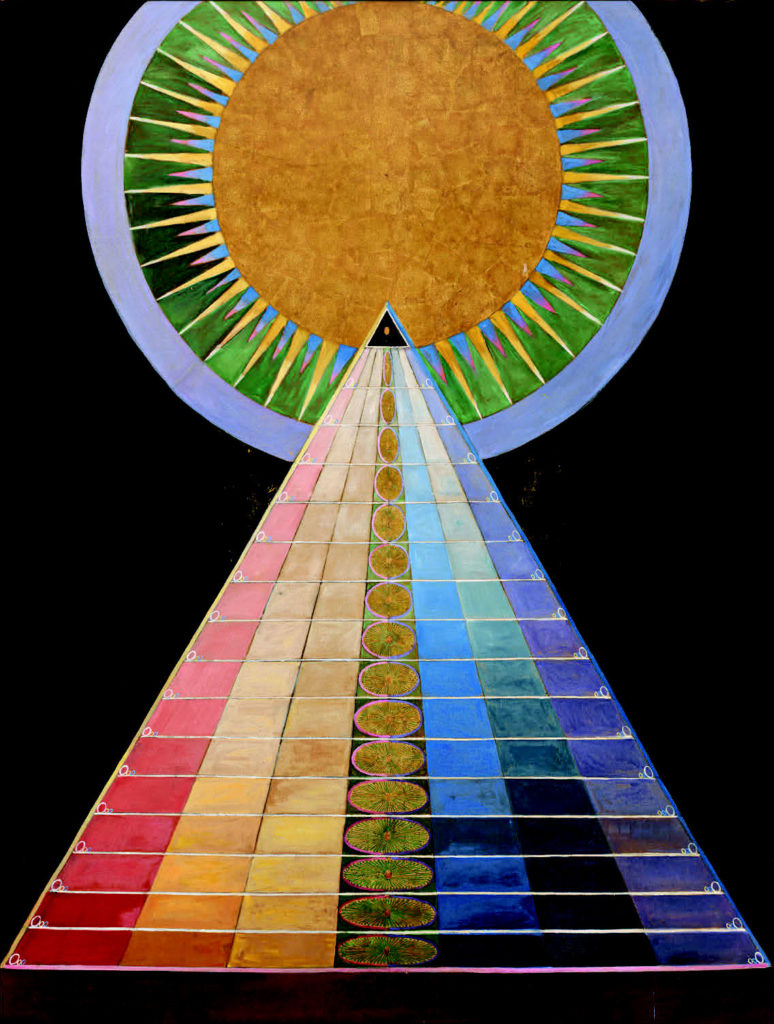

Fig. 7. Grupp X, nr 1, Altarbild [Group X, no. 1, Altarpiece], 1915. Oil and metal leaf on canvas, 93 ½ by 70 ½ inches.

Stewarding the collection according to the artist’s wishes, af Klint’s family did not view the works until 1966, and in 1972 started the Hilma af Klint Foundation to safeguard her legacy. Her work was not shown in the United States until 1986, when Maurice Tuchman included af Klint in his landmark exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In 1986, critics were astonished and perplexed to see af Klint’s work placed alongside that of Vasily Kandinsky(1866–1944),Piet Mondrian(1872–1944), ANTIQUES Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935), and Frantiek Kupka (1871–1957), and even protested her inclusion among this group still regarded as the protagonists of abstract art. In fact, having developed an abstract imagery in 1906, several years before the others, af Klint was herself a pioneer in this radical approach to painting.

Fig. 8. Grupp IV, De tio största, nr 7, Mannaåldern [Group IV, no. 7, Adulthood], part of The Ten Largest series, 1907. Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 124 by 92 ½ inches.

Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York from October 12 to February 3, 2019.

ANNE WHEELER is a New York–based curator and art historian.