When the Trump presidency ends, commentators will doubtless launch into a furious round of assessment. Among the motifs in this stock-taking, a humble article of clothing is sure to take on an outsize role: the red baseball hat, machine-embroidered with the legend “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.”

The MAGA hat is a brilliant piece of branding, in that it tacitly analogizes Trumpism to America’s national pastime. Much that people love and hate about Trump seems embodied in it: a certain primal, anti-elitist truculence; an unapologetic nationalism, premised on the idea of a singular, exceptional, and homogenous country. Fascinatingly, too, it was met by an opposite number, the iconic Pussyhat, feminist pink and handmade. It’s become commonplace to juxtapose the two as emblematic of our divided country.

For students of material culture, all this makes for absorbing scrutiny. But what would really be great for America right now would be to get past oppositions, past loving and hating. People seem to agree on this, if on nothing else; there’s been talk of an “exhausted majority,” whose primary political ambition is for everyone to just stop shouting.1

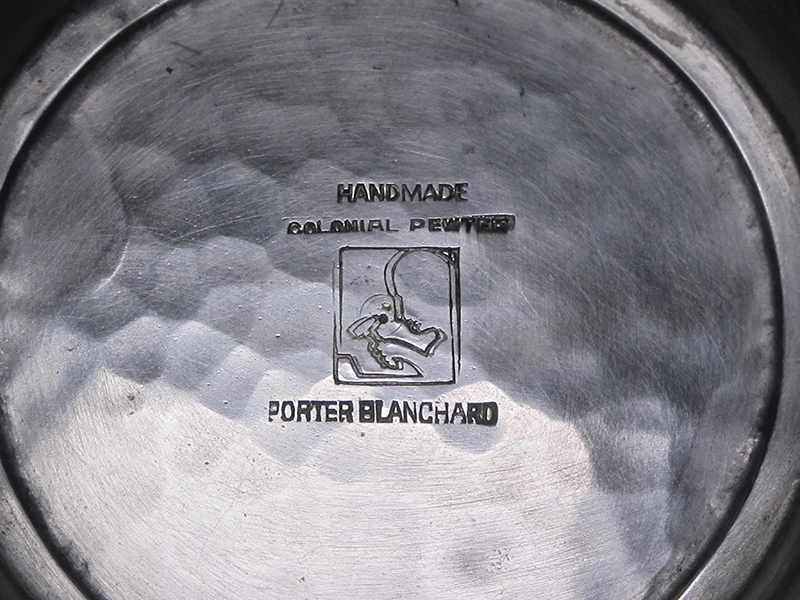

Pewter bowl by Porter Blanchard, c. 1930s. Photograph by Edward S. Cooke Jr.

Sadly, getting past no! has turned out to be elusive. As a modest contribution to this effort, let’s look at a precedent: a metal bowl, currently sitting in the office of Edward S. Cooke Jr., a professor at Yale University. I know him as Ned, because I studied with him in graduate school days and co-taught a class with him last semester. The bowl, one of a number of items he has collected for teaching purposes, was made by Porter Blanchard, likely in the 1930s. Though only about six inches in diameter, its shape will be immediately recognizable to antiques aficionados as that of a colonial punchbowl—specifically, the famed Sons of Liberty Bowl by Paul Revere, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Blanchard was from Massachusetts—he learned the silversmith’s trade from his father—and in 1923 moved to California. Soon he was running a shop in Hollywood. He did make a lot of silver cutlery and hollowware, but also had a line in pewter, the material used for Ned’s bowl.

In our class, we passed the Blanchard bowl around with the students, and asked them how they thought it was made. It’s covered with slight indentations, and on the underside there is a double-struck hallmark that shows an outline figure of a hammering smith. So they guessed (reasonably enough) that it was hand-raised. But of course, that’s not how pewter is formed; it’s cast in a mold, making it ideal for serial production. The fake hammer marks refer to eighteenth-century craftsmanship, but they are totally decorative.

The students laughed when they realized that Blanchard’s “Handmade Colonial” object was neither. This blithe disregard for accuracy, fused with a genuinely celebratory attitude to the past, was typical of the colonial revival. The nostalgic hand-tinted photographs and reproduction furniture of Wallace Nutting, wildly popular in the 1920s and ’30s, similarly conflated the genuine and the fictional. This sanitized picture of a quaint American past became, in the words of Nutting scholar Thomas Denenberg, “an endlessly self-referential business empire that catered to the culturally conservative needs of middle-class America.”2

It isn’t hard to see the connections between Blanchard and Nutting, and contemporary expressions of nationalism. Lest we forget, the first wave of recent right-wing activism marketed itself as the Tea Party (another inspired piece of branding). Opponents of this tendency in American politics are of course delighted to expose its hypocrisies—as when it emerged that many MAGA hats worn to Trump’s rallies are knockoffs, made cheaply in China; and that even the legitimate manufacturer that produces the red caps, as of 2015, employed an estimated 80 percent immigrant Latino workforce.3

Rather than playing a game of gotcha, however, the real lesson here is that no one should claim possession of a single truth about America. The historian Jill Lepore, in her book The Whites of their Eyes—published in 2011, as the Tea Party was on the rise—pointed out that politicians of all stripes have invoked the Founding Fathers for two centuries now.4 During the Nixon administration, Democrats drew parallels between the tyrant Richard and King George III, which is not much more convincing than Blanchard’s bowl.

The bowl’s hallmark was double struck. Cooke photograph.

Lepore’s point was not that we should forget about precedent, never seeking out analogies to our own time. Rather, she argued that we should understand history as constantly under revision. We should avoid “historical fundamentalism,” the notion that anyone in the past operated from simple and easily comprehensible motives. The same goes for people in the present. Lepore has often been critical of the reductive (and flatly inaccurate) accounts of the past that circulate in right-wing circles. But she is also rightly sympathetic to the emotional longing “for a common past, bulwark against a divided present, comfort against an uncertain future.”5

The colonial revival, which flourished during the Great Depression, really did help people come to grips with their volatile present. It did so through distortion—encouraging people to see their country as easy to understand, unified, and unproblematic. Many Americans still want that wish fulfilled, and who can blame them? In an increasingly interconnected world, it is difficult to get our bearings, even to accurately ascribe blame when bad things happen.

Given all this, it’s likely that in retrospective assessments of Trump, he will be understood more as a symptom than a cause. The best response to his demagoguery will not be left-wing revolution, nor ongoing culture war. Rather, we need to make peace with complexity itself. The thoughtful study of objects past and present can make a contribution to this goal. As the MAGA hat and the Blanchard bowl suggest, artifacts are often at their most artful when they pretend to be least affected. This sort of insight may help us all to see that America has never been a simple place. Spoiler alert—it never will be.

1 Sabrina Tavernise, “These Americans Are Done With Politics,” New York Times, November 17, 2018. 2 Thomas Andrew Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Wadsworth Atheneum, 2003), p. 3. 3 “Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ Hats Fall Short on Made in USA Tags,” Associated Press, July 8, 2016; David Anderson and Graham Flanagan, “Inside the Trump ‘MAGA’ Hat Factory,” Business Insider (blog),September 18, 2018. 4 Jill Lepore, The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle Over American History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011). 5 Ibid., p. 97.