The Paston Treasure by artist known as the Master of The Paston Treasure, c. 1663. Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norwich, UK, courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service NWHCM.

Bass viol, London, c. 1640–1665. Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, bequest of Robert Alonzo Lehman.

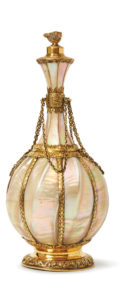

Although a new exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World, contains nearly 140 objects, it is centered around a single painting. As these things go, The Paston Treasure is a very large painting indeed, more than eight feet wide and nearly five and a half feet tall. Within its capacious frame it contains multitudes. All of creation, you might think, has been shoved pell-mell into its impressive breadth. A table, rising up before a classical column from which a crimson drape is hanging, has been loaded with a world of riches: a globe and lute, silver-gilt flagons, nautilus cups, a perfume flask fashioned from mother-of-pearl, as well as a trumpet, an hourglass, flowers, and fruits. The very grapes are spilling over the tabletop, which already appears in a state of giddy disequilibrium, due to the odd two-point perspective.

Nautilus cup attributed to Nicolaes de Grebber, 1592. Museum Prinsenhof Delft, Netherlands, acquired with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt.

In the center of the table is a lobster, which might seem almost surrealistic in any other context, but makes perfect sense in this one, whose entire point is sensory overload and the unstinting abundance of the pleasures of this world. Two human beings—a young girl in the foreground and a young boy with a monkey seated on his shoulder—manage to get lost amid this extravagant sumptuosity. A number of the objects in the painting, among them a Strombus shell cup, two of the nautilus cups, and the mother-of-pearl flask, appear in the show, brought together for the first time in more than three centuries.

One of a set of flagons, 1598. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Irwin Untermyer.

We do not know exactly why or by whom The Paston Treasure was painted. Scholarly consensus seems to coalesce around the likelihood that it is the work of some anonymous Dutch master of the later seventeenth century, and the curators of the show surmise a date of around 1663. Although it is an indoor scene, its sunlit brilliance and the blond tonalities of the objects suggest a later date, when Dutch still lifes were moving away from the pietistic chiaroscuro of Jan Davids de Heem or Pieter Claes that was fashionable in the middle years of the seventeenth century.

The work, which was acquired by the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery in 1947, was commissioned either by Sir William Paston, first Baronet (1610–1663), or by his son Robert, the first Earl of Yarmouth (1631–1683), both of them distinguished Norfolk landowners and scions of the family best known for the so-called Paston Letters, a running commentary on English affairs for most of the fifteenth century, especially the War of the Roses.

Pietre dure tabletop , c. 1625, with coat of arms, 1638. Private collection.

Mother-of-pearl flask with silver-gilt mounts, c. 1650–1660. Private collection.

Amid the treasures that overburden the table, the globe and hourglass and perishable fruits and flowers are some of the staples of Dutch baroque still-life paintings. In this context they suggest a certain philosophical elevation, a questioning of the vanities of this world. But don’t be fooled: the painting is about nothing so much as conspicuous consumption. In our day the painting itself is the trophy, but in its own day it was subordinated to the objects it depicted, which were intended to excite the admiration and, better still, the envy of all those gentry fortunate enough to be admitted into the distinguished home of the Paston family.

The exhibition is accompanied by a scholarly book, copublished by the center and Yale University Press.

The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World • Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT • to May 27 • britishart.yale.edu