When architect William Purcell built a home for his growing Minneapolis family, he sought more than the usual comforts of upper-middle class life. He wanted a manifesto made of timber and stucco, an argument he could inhabit, a calling card for potential clients, and a whimsical domain in which he could ignore the strictures of bourgeois life circa 1913. What came of those aspirations can still be seen on a tree-shaded street near one of the city’s celebrated lakes. The Purcell-Cutts House, located at 2328 Lake Place, is one of the nation’s most elegant Prairie school homes, and a summary of all that Purcell and his design partner, George Elmslie, had learned while working beside Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and other Chicago visionaries who upended the conventions of Beaux-Arts architecture before World War I.

“What we needed to do,” Purcell wrote in his “Own House Notes” about 1915, “was to lose, not so much the parlor as the parlor idea of life—and when that went the resulting change in form bore witness to a very definite occurence.” Purcell’s house still looks like a “definite occurence” amid the eclectic, revival homes that surround it. Set back about thirty feet from the sidewalk, the two-story, twentyfour- hundred-square-foot residence casts an immediate spell with its geometric facade. Composed of interlocking rectangular forms, it sets horizontal elements— overhanging eaves, cantilevered masses, and bands of decorative stenciling—against the upward thrust of a prominent chimney and the house’s most stunning period signature: a wall of soaring art glass windows in the east-facing living room.

That bravura first impression continues when one enters the house, which breaks from convention with a fluid, open plan design. The main public areas, both visible from the entry, are linked by a tented ceiling, about fifty feet long, which stretches above the dining area and a sunken living room. Sparely furnished, as it was in Purcell’s day, the living room invites varied activities with its raised hearth, office nook, and a long bench under wraparound art glass windows. Those interiors have been closed during the Covid-19 pandemic, but the Purcell-Cutts House, owned by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, reopens for tours this spring.

Only a handful of Prairie school residences are open to the public on a regular basis, so the return of Purcell and Elmslie’s masterpiece is significant for fans of that influential period style, says curator Jennifer Komar Olivarez. She oversees the house and serves as head of exhibition planning and strategy for the museum. For her, the house is a key part of MIA’s overall collection, which features a notable amount of Prairie school furniture and architectural elements and puts them in context with its vast holdings of modernist decorative arts from Europe. In addition to the Purcell-Cutts House, she advises museum patrons to visit MIA’s “period room by Minneapolis designer John Scott Bradstreet, who knew Purcell and Elmslie, and our Asian collection, which includes a Chinese reception hall, two Japanese period rooms, and many objects that remind one how much Asian art influenced the school architects.”

Olivarez spent more than two years as the resident caretaker of Purcell’s home in the mid-1990s. The property had come to the museum as a 1985 gift from Anson Cutts Jr., the son of the couple who had purchased it from Purcell in 1919 and left the residence largely unaltered.

“Living in the house helped me see how much it is connected to nature,” Olivarez says. “On sunny mornings, the pool and fountain in front of the house cast rippling reflections on the tented living room ceilings. When I opened windows, I could hear birds and the tinkling fountain. On some afternoons, light spilled through the small, south-facing window that Purcell’s wife, Edna, wanted at ground level over her desk. And, because the house is set back from the street, I looked into neighboring gardens, not neighboring houses.”

As resident caretaker, Olivarez also grew to appreciate the meticulous detailing that makes the house special. “On a quick walkthrough, a visitor might miss the iridescent glass embedded in the mortar of the fireplace, or the many subtle variations in the art glass window designs. And it takes a while to see that every element pulls the house together: the same unstained oak in millwork, bookcases, and the hallway screen; the decorative stencils, the custom rugs and the furniture designed by Purcell and Elmslie’s firm.”

Despite that integrated design, it remains a temptation to tease out the parts that owe most to Elmslie, or to Purcell, or to Edna Purcell, who offered important feedback during design and construction. The game gets some of its savor from the outward differences of the architectural partners: Elmslie, a Scotsman, was more than a decade older than his partner, an enthusiastic Chicago native who had grown up just blocks from Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio in the suburb of Oak Park. Elmslie met Purcell at a social event, just after the latter’s 1903 graduation from Cornell University’s architectural school—and Elmslie immediately hired Purcell to join him on the staff of Louis Sullivan’s firm. Already an established figure in Chicago, Elmslie had secured his own spot in Sullivan’s office in 1889 on the recommendation of Wright, and by 1895 had become Sullivan’s chief draftsman, a position he would hold for fourteen years.

What started as a mentoring relationship between Purcell and Elmslie, turned into an equal partnership when Purcell invited the older man to join his Minneapolis firm in 1910. “There’s no doubt that Elmslie brought special strengths to the firm as draftsman and designer of organic decorative motifs. He could do that kind of thing in his sleep,” Olivarez says. “For a good example, go to the Northwest Architectural Archives [at the University of Minnesota], which has Elmslie’s sketches for the home’s art glass windows.”

Yet the new firm added up to more than the sum of its parts, Olivarez says. “You can see that both architects were shaped by the same creative ecosystem. They ran their firm in an egalitarian manner—and even hired a woman, which was quite rare at the time. One can’t always draw clear lines between the contributions of Purcell and Elmslie, but it’s obvious that their juices were flowing when they designed the Purcell-Cutts House.”

For Olivarez, the house on Lake Place is a total work of art, one that ranks with other homes that great architects have designed for themselves. “This isn’t just a house for people who like the Prairie school,” she says. “It’s as unified as Eliel Saarinen’s art deco residence at Cranbrook; as much an experiment in living as the Schindler House in Los Angeles; as much of a showcase for creative teamwork as the Case Study House of Charles and Ray Eames.”

Those sentiments were echoed by Minnesota architect Tim Quigley, who has served for years on the board of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy. “This house was made for modern living,” he says. “It feels like you could move in comfortably, which isn’t always the case with historic buildings.”

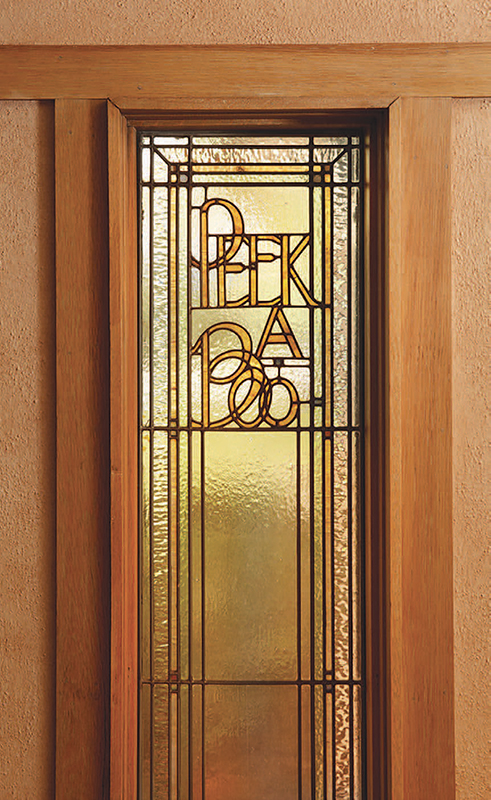

If the house engenders good feelings, some of that comes from the whimsical personal details that temper the elegance of its design. “It’s not exactly aloof,” Quigley says. “The partners had a name for the house—‘The Little Joker’—and it’s easy to understand why. Just look at the art glass windows that frame the front door, decorated with the words ‘Peek A Boo.’ And if you’re in the living room, you can’t really miss the fairy tale sculpture of a boy flying on the back of a goose.”

The scale of the house is especially appealing to Quigley. “It’s the opposite of a Newport mansion— and that’s a good thing,” he says. “For most architects, their biggest projects are rarely their best. They need constraints to bring out their creativity. The Purcell- Cutts House is a study in overcoming constraints— built on a middle-class budget, and fitted into a small, level city lot. I can almost picture Purcell and Elmslie working through the problems, trading ideas, getting excited. In the end, they produced one of the finest Prairie school homes—a totally integrated masterpiece.”

Visit artsmia.org for details on tours of the Purcell-Cutts House.

New Orleans journalist CHRIS WADDINGTON is a regular contributor to The Magazine ANTIQUES and other national publications. His many awards include two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships for critical writing.