A Young Girl Reading by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, c. 1776. All images courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington; gift of Mrs. Mellon Bruce in memory of her father, Andrew W. Mellon.

Surely you already know Fragonard’s Young Girl Reading or La Liseuse, one of the most popular works in the National Gallery in Washington. This image, which has adorned countless book-covers, posters and coasters in recent years, depicts a pretty young woman in a yellow dress, daintily holding a small volume in her right hand, while her left hand rests on the arm of a chair that rises before a pale brown wall.

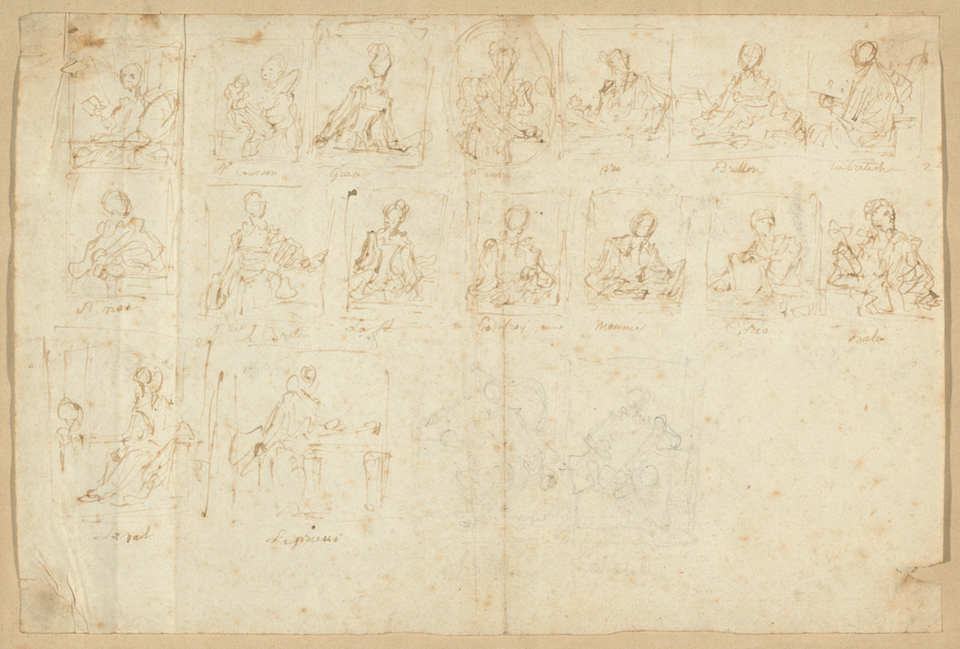

Until recently, however, few of this work’s many admirers suspected that it was part of a much larger and illustrious family of tetes de fantaisie, or fantasy portraits, that Fragonard created in the 1760s, when he was just establishing himself on the Parisian art scene. In 2012, however, scholars discovered a drawing sheet, apparently by Fragonard himself, with thumbnail depictions of La Liseuse and thirteen other fantasy portraits, as well as four related images that have not yet been identified. Little more than pictorial short-hand to serve as a record of his works, this sheet identifies most of the sitters by name. Now a landmark exhibition at the National Gallery, curated by Yoriko Jackall, reunites La Liseuse with her long-lost siblings and the newly discovered drawing sheet.

Sketches of Portraits, c. 1769. Private Collection, Paris.

These fourteen images embody, as forcefully as anything Fragonard ever produced, what the world loves about his art. Their brio, painterliness and carnality are unheard of in the well-behaved portraits of more mainstream contemporaries like Nattier, Du Plessis and Toque. And the brilliance of their technique is matched only by the fulgurant speed with which they were produced: although their dates are not certain, it is thought that all of them, and the drawing sheet as well, are from 1769.

These images, all of them half-length portraits, cannot be called “Romantic,” in the sense in which Delacroix, half a century later, would deserve that term, but their energy and power prefigure those of a later age. The painting known as The Actor, which the current exhibition identifies as Gabriel Auguste Godefroy, depicts a handsome young man in seventeenth century attire, his finely delineated features rising above a ruff. Seen from slightly below (in what cinematographers call an “epic shot”) the golden yellow of his sleeve flickers like fire in a gale, almost threatening to engulf the entire composition. Likewise, the noble portrait of the Abbe de Saint-Non, whose blue and orange draperies “stream like a thunderstorm against the wind,” as Byron would later say, presage by two generations the violent energy of Gericault.

The Actor, c. 1769. Private Collection.

Meanwhile, a slightly calmer mood suffuses the lovely Portrait of a Woman, traditionally thought to depict the ballerina Mlle. Guimard, but now believed to represent Marie-Anne-Éléonore de Grave. Like the others tetes de fantaisie, this sylph-like creature is attired in vaguely 17th century garb, not at any rate the attire of a Parisian late in the reign of Louis XV. Amid the riot of the brushstrokes the define her body and clothes, Fragonard comes to rest in the face, upon which he lavishes all the fine details and pearline fleshtones of Watteau at his best, half a century before.

Most of the tetes de fantaisie, however, falls short of that degree of specificity, which they never sought in the first place. In their winsome way, they initially appear, despite their painterliness, to fit squarely within the traditions of Western portraiture, the traditions of Raphael and Titian, of Velasquez and Rembrandt: they depict elegantly clad men and women, mostly in three-quarter view, but sometimes in profile or nearly frontal. On closer inspection, however, they prove to be some of the strangest works in the entire corpus of Old Master painting. For they do not behave like conventional portraiture: there is, simply put, something odd, something off about them.

Woman with a Dog, c. 1769. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1937; photograph © Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

What, after all is a portrait, a genre that never enjoyed greater cultural prestige than in eighteenth-century France? It is the union of the universal and the particular in the context of a specific human being. Portraits differ from those countless depictions of gods and saints, angels and nymphs, that populate so many works in the Western canon, in that they depict a radically specific human being rather than a generic type. At the same time, however, they differ from a forensic record of a human face (a death-mask, for example) in that their specificity has been animated by a generalized human vitality without which we could not intuitively identify with and respond to the soul of the sitter.

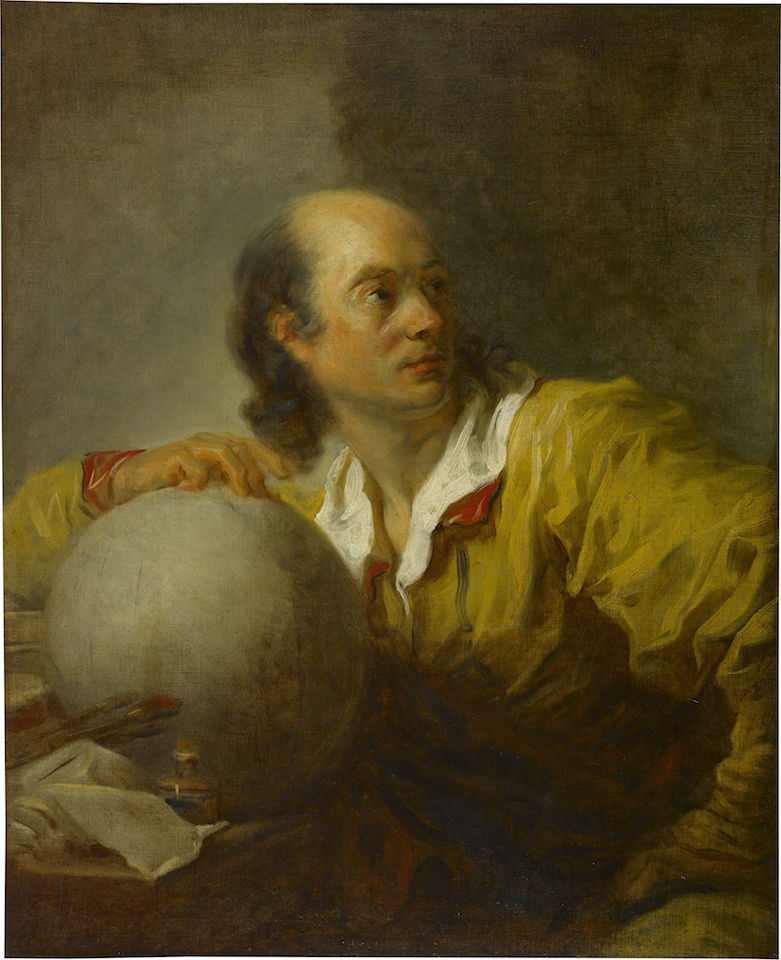

Portrait of a Man, c. 1775. Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris; photograph © Petit Palais / Roger-Viollet.

But if Western painting has traditionally vacillated between the general type and the radical individual, Fragonard’s tetes de fantaisie offer us a third way. Without quite tipping over into type, his sitters have been abstracted to a degree of beguiling generality. Through an experiential illusion, they simultaneously approach and recede from the specificity that we expect of portraiture. If some of these sitters, like Mlle. Guimard and the Abbe de San-Non, would be easily recognized by their contemporaries, the two men depicted in Portrait of a Man and Man in Costume occupy a zone poised unstably between portraiture and myth.

For such reasons as these, Fragonard’s tetes de fantaisie have considerable importance in their history of art. It is not an exaggeration to say that they represent the point where the tradition of the Old Masters goes off the rails. That is not to say that they represent any loss of control. Rather it is to insist that they define their own journey going forward, rather than remaining within the path prescribed to them by precedent pictorial tradition, a tradition that even rebels like Caravaggio implicitly obeyed even as they expanded it.

Man in Costume, c. 1767–1768. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mary and Leigh Block in honor of John Maxon, 1977.123; photograph © The Art Institute of Chicago.

Put another way, these tetes de fantaisie reveal their proto-modernity in a stunning display of that sovereign artistic freedom that would eventually move Picasso to depict Kahnweiler as a congeries of cubist facets and Warhol to immortalize Marilyn as a sequence of silk-screened multiples. Like them, Fragonard, for the first time, not only chooses the color and composition of the painting, but invents from scratch the entire context, indeed the entire universe, in which they occur. At the highest level of generality, this is the future of Western art. Though usually thought to begin with Courbet in the 1850s, its embryonic stirrings can already be detected, nearly a century before, in the art of Fragonard.

Fragonard: The Fantasy Figures • National Gallery of Art • Washington, DC • to December 3 • nga.gov