Throughout her career, photographer Dorothea Lange was determined to never “molest, tamper, or arrange,” and always to capture “a sense of place.”1 For her, directness and simplicity were the path to authenticity and truth, and honesty was the medium of exchange between photographer and subject. Dorothea Lange: Seeing People—an exhibition currently on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC—offers a wide-ranging look at her practice and how her images came to not only shape documentary photography but deepen our sense of what a portrait can be.

Born in New Jersey, Lange worked in the studio of photographer Arnold Genthe and studied with the father of the pictorialist school of photography, Clarence H. White, at Columbia University. She headed West in 1918 on the first leg of what she hoped would be a round-the-world adventure, but came to rest in San Francisco, where she landed a job in the photofinishing department of Marsh and Company. Before long, she opened her own portrait studio and found success with well-off sitters. In 1920 she married Maynard Dixon, an established artist known for western subjects. Accompanying him when he went to Arizona and New Mexico to sketch and paint, Lange became acquainted with the western landscape and various Native American communities.

Returning to San Francisco in 1932, after a months-long sojourn in Taos, she was struck by the altered landscape of the city, where the unemployment rate surpassed the national average and bread lines formed in the streets. She returned to her studio, but she was not content. “I enjoyed every portrait that I made in an individual way, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to do. I wanted to work on a broader basis,”2 she recalled. In 1933 she stepped outside and set her career in a whole new direction. Heading to the waterfront, she encountered a soup kitchen, where she shot what would become one of her most famous pictures: White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, California, which showed a mass of men, all in hats, with one fellow turned away from the crowd and leaning on a fencepost, his hands clasped as if in prayer. “I put it on the wall of my studio, and customers, people whom I was making portraits of, would come in and just glance at it. The only comment I ever got was, ‘What are you going to do with this kind of thing? What do you want to do this for? What are you going to do with this thing?’ That was a question that I couldn’t answer.”3

Still uncertain of where this new work would lead, Lange continued to hit the streets, documenting May Day meetings and worker demonstrations. But in 1935 she found an outlet for her growing interest, first with the State Emergency Relief Administration, which used her photos to illustrate a report on migrant workers, and then with the Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Issued assignments from the FSA office in Washington, Lange spent months traveling through the West and South documenting the hardships of displaced farmers, struggling sharecroppers, and wage-seeking migrants. Looking back on that experience decades later, she remarked: “The people who are garrulous and wear their heart on their sleeve and tell you everything, that’s one kind of person, but the fellow who’s hiding behind a tree, and hoping you don’t see him, is the fellow that you’d better find out why. You know, so often it’s just sticking around and being there, remaining there, not swooping in and swooping out in a cloud of dust; sitting down on the ground with people, letting the children look at your camera with their dirty, grimy little hands, and putting their fingers on the lens.”4

After years of shooting in the streets and fields, in tired towns and migrant camps, Lange was utterly committed to truth-telling photography, to bearing witness to hard times and desperation. Her position at the FSA came to an end in 1939, but in 1941 she was hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to document—oddly enough—the prosecution of Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of more than a hundred thousand Japanese Americans. Lange followed Bay Area residents as they closed up homes and businesses and she visited the relocation camp at Manzanar, California. In a letter to Ansel Adams, who was also hired by the WRA, Lange wrote: “We have a disease. It’s Jap-baiting and hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don’t know a more challenging nor more important one. I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing.”5

In the 1950s and ’60s, Lange found herself far from her California home, shooting in Ireland, Nepal, Egypt, and Korea. While the images of those final decades reflect the direct, unmediated approach she had adopted decades before, it is her work of the Depression and war years that reads most forcefully today. We may appreciate their formal values more fully than did viewers of the past, but she always deemed herself an observer, not an artist, and it is her power of observation, her willingness to disappear, to allow a narrative to emerge unhindered, that endows her photographs with a rough, eye-opening beauty.

Untitled (La Estrellita, “Spanish” Dancer), San Francisco, California, 1919

A well-born girl from Cincinnati, Stella Hurtig Jones made her name dancing flamenco and tango in vaudeville. She performed for Queen Victoria; took Lord Kitchener, the British governor of Egypt, as a lover; and was famous enough to be mentioned in a Jack London short story, “The Kanaka Surf.” She retired from the stage in 1921, married, launched a perfume company, and settled into a twenty-three-room Bay Area mansion.

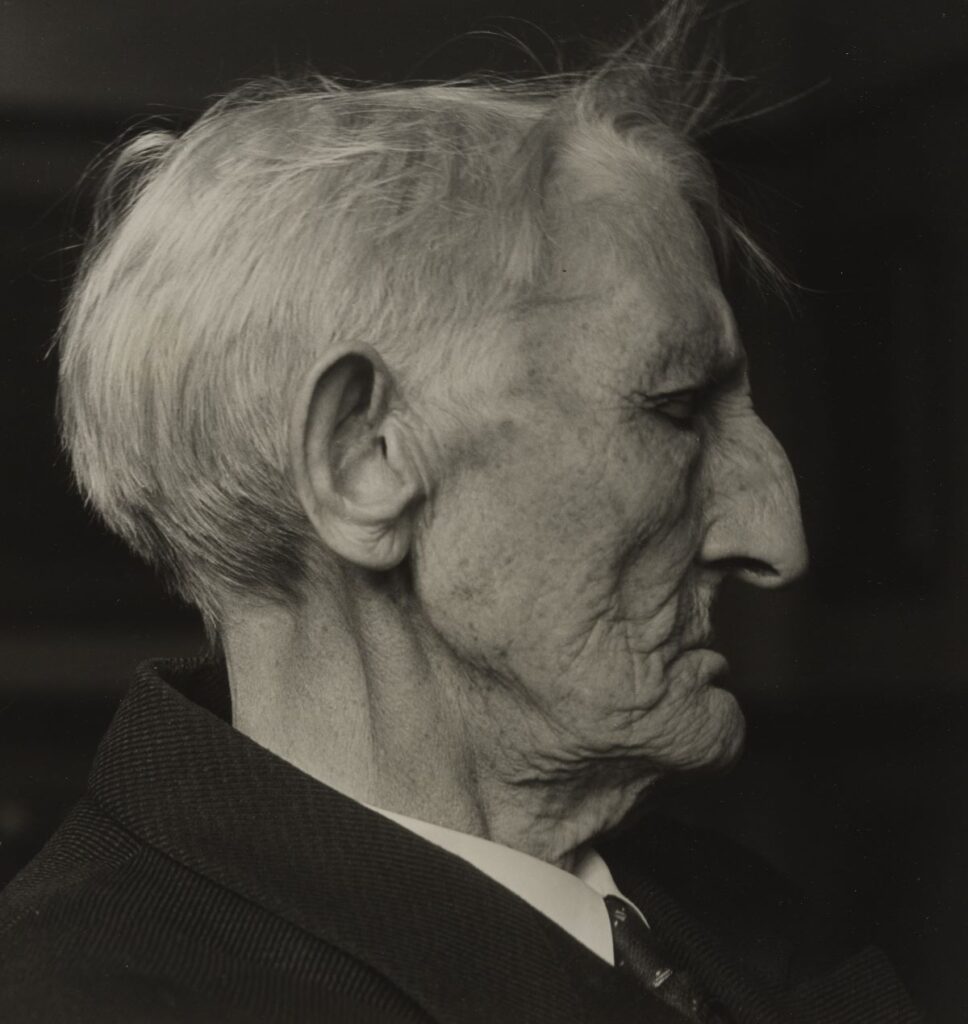

Andrew Furuseth, 1934

President of the International Seamen’s Union, veteran associate of labor leader Samuel Gompers, the Norwegian-born Furuseth had gone to sea at nineteen. A tall, gaunt man who dressed in baggy, wrinkled suits and never shared much of himself, he was a formidable crusader for workers’ rights and became known as the Abraham Lincoln of the Sea.

Dorothy Brett, Painter, Taos, New Mexico, 1931

The bohemian daughter of a British viscount, Brett attended London’s Slade School of Fine Art, where she studied under painter Augustus John. Her social circle included Virginia Woolf, Aldous Huxley, and D. H. Lawrence and his wife, Frieda. In 1924 she accompanied the Lawrences to New Mexico, where she became enthralled with the landscape and Pueblo culture. She remained there the rest of her life.

Member of the congregation of Wheeley’s church who is called “Queen” . . . , July 1939

Wearing a homemade dress and apron and sporting a substantial sunbonnet, “Queen” Bowes was a member of Wheeley’s Church, a conservative Baptist congregation in Person County, North Carolina, where men and women accessed their meetinghouse through separate doors.

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, California, 1933

One of Lange’s first street photos, this now-classic shot was taken not far from her San Francisco studio, at a soup kitchen on the Embarcadero in an area known as the White Angel Jungle. Unaccustomed, as she later stated, “to jostling about in groups of tormented, depressed and angry men with a camera,” she took her brother Martin along with her.6

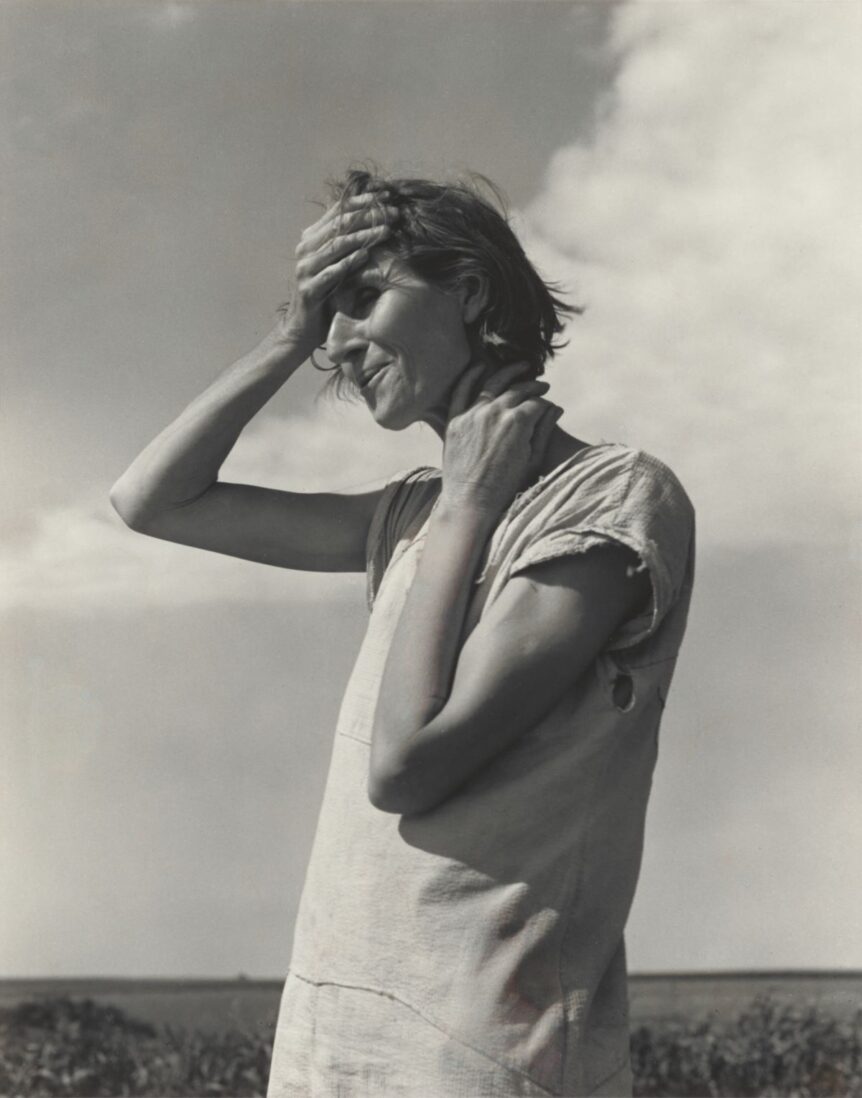

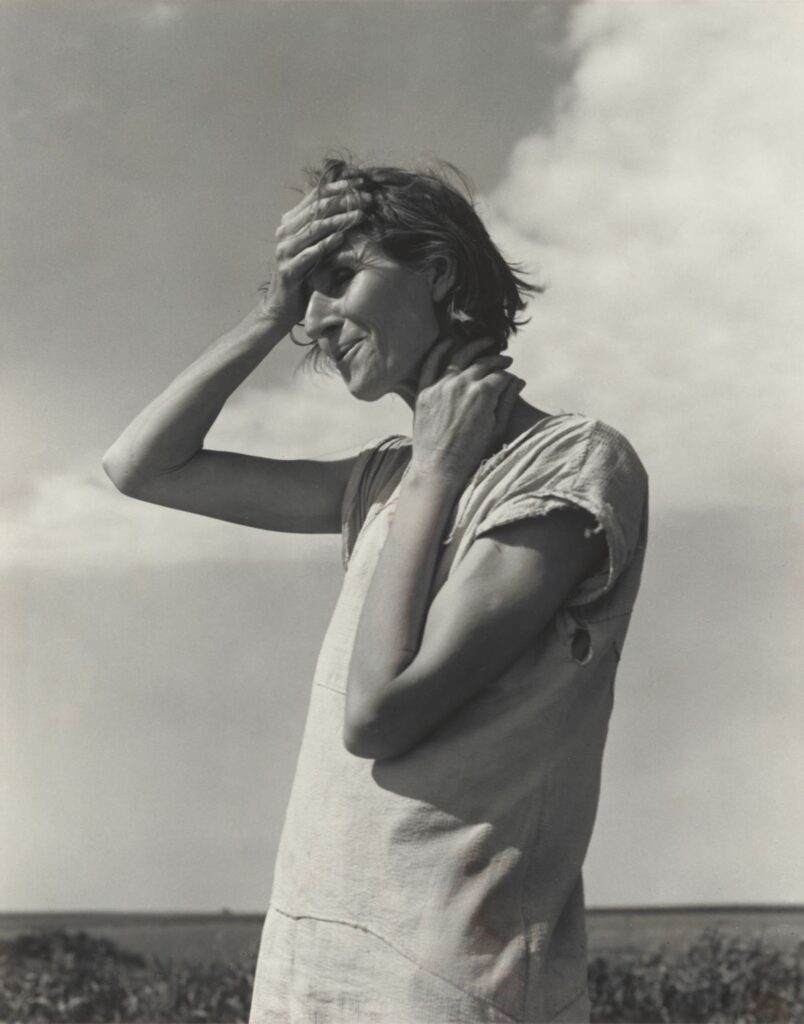

Nettie Featherston, Wife of a Migratory Laborer with Three Children, near Childress, Texas, June 1938

A Dust Bowl exile from Oklahoma, forty-year-old Nettie Featherston was headed to California, but had only made it as far as North Texas when Lange photographed her on a farm, where she was given the use of a two-room shack in exchange for picking cotton.

Rebecca Dixon Chambers, Sausalito, California, 1954

inches. National Gallery of Art, Greenberg and Steinhauser gift, © The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland, gift of Paul S. Taylor.

Dixon, whose roots went back to colonial Virginia, was born in California. Her ancestors had been slaveholders in Mississippi, and the family migrated West after the Civil War. “Now,” Lange wrote in a brief note, “she tends her flower garden on a Marin County hillside.”7

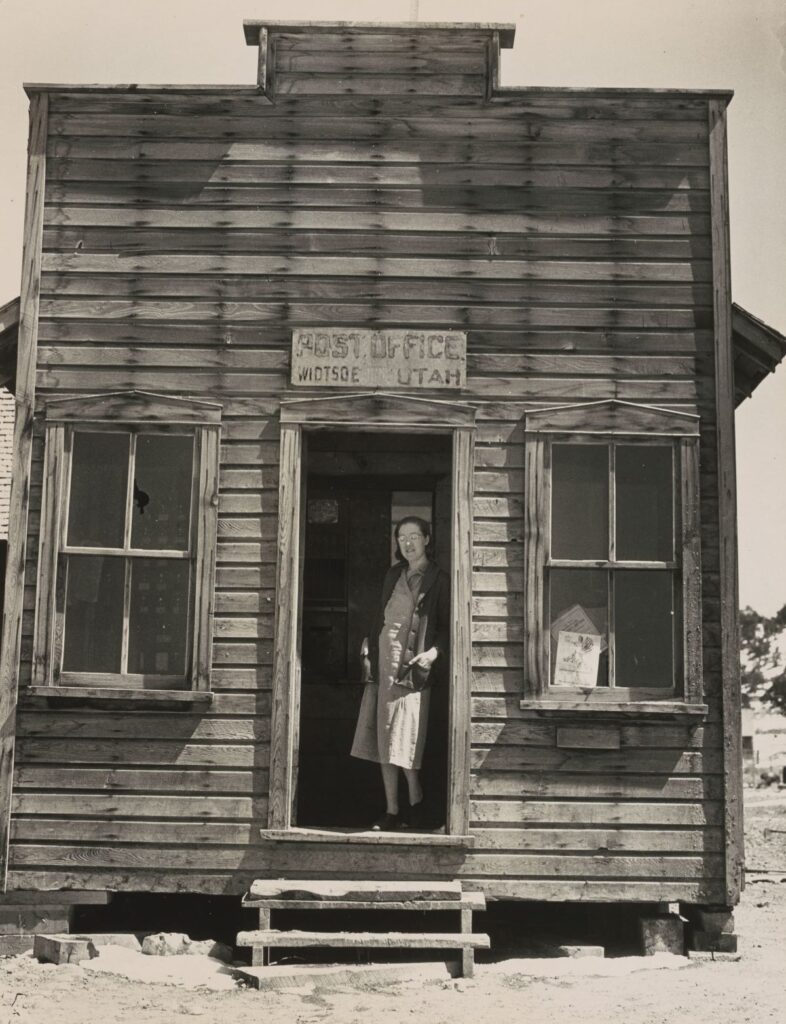

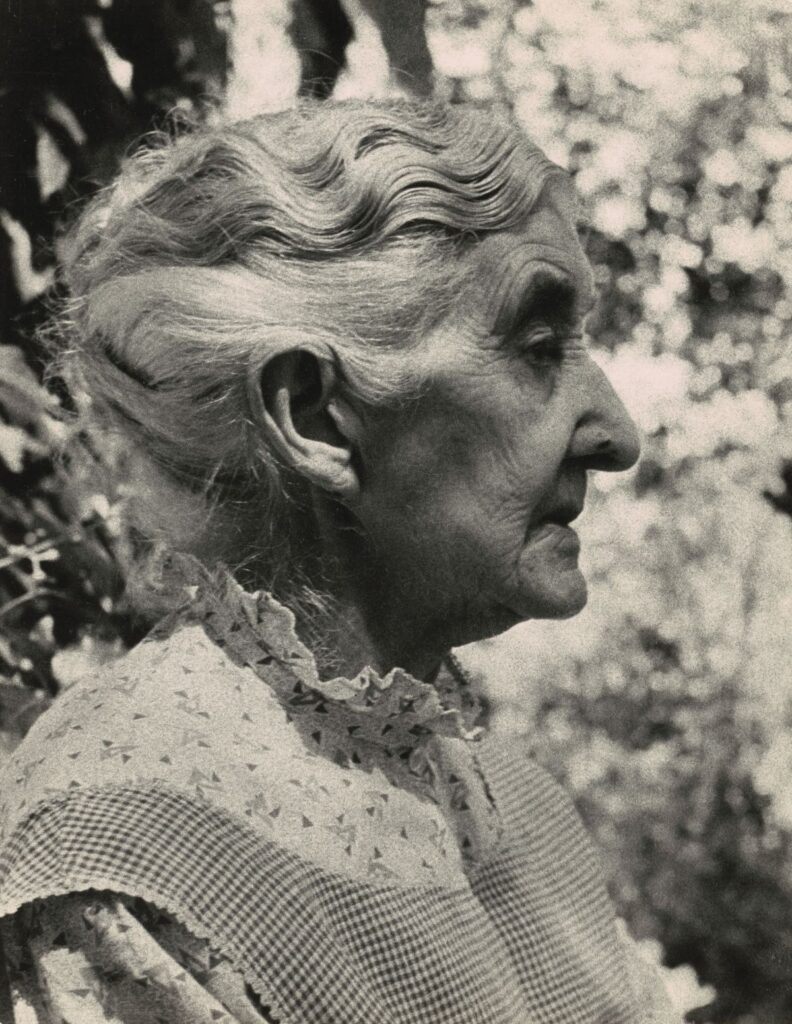

Mary Ann Savage, a Faithful Mormon All Her Life, Toquerville, Utah, 1931

Savage crossed the plains with her family in 1856 when she was six years old. She died five years after this photo was taken. In 1953, while on assignment for Life, Lange returned to Utah and photographed her headstone.

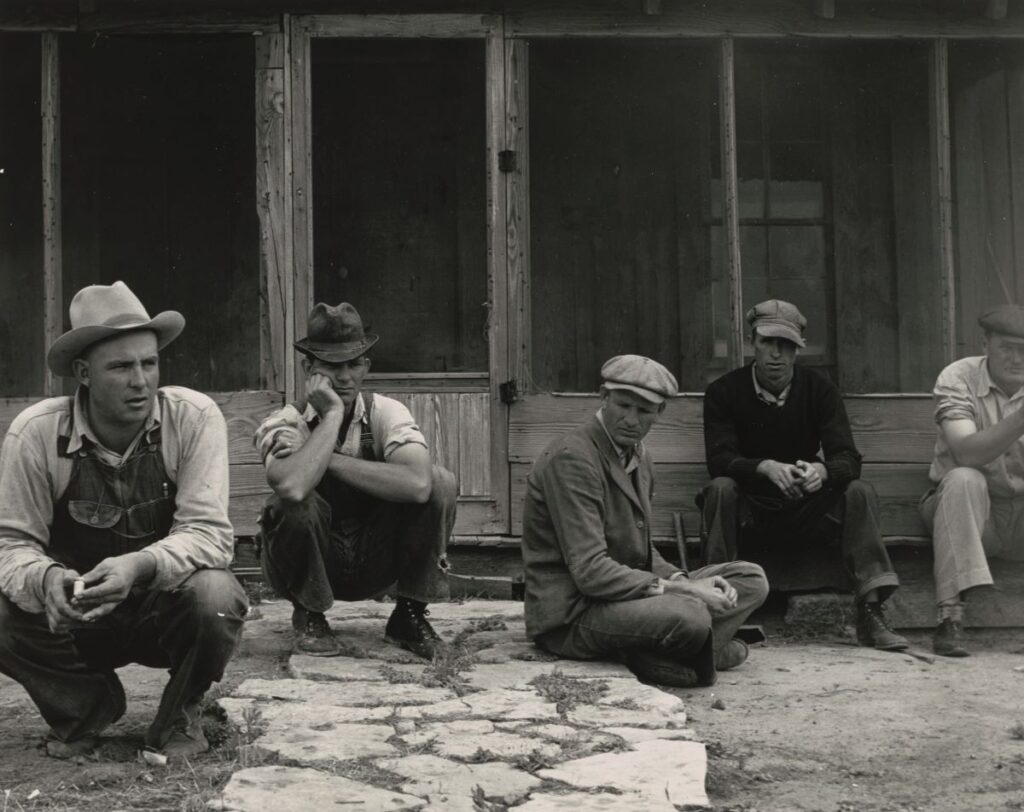

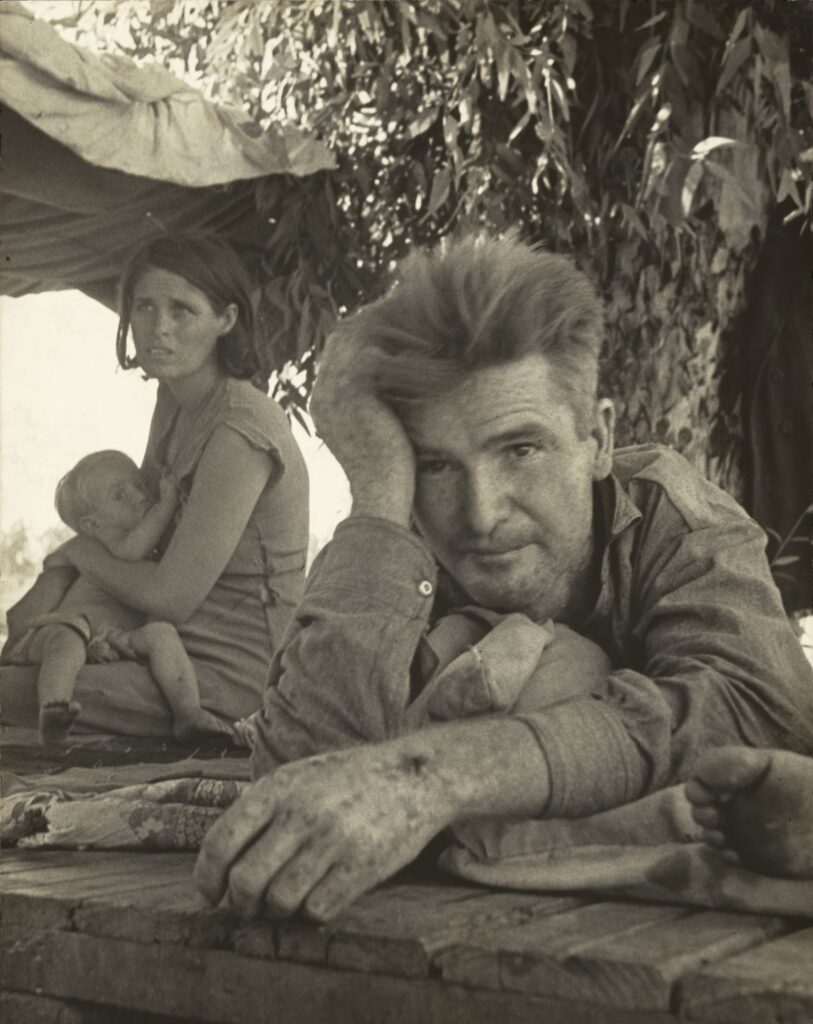

Drought Refugees from Oklahoma Camping by the Roadside, Blythe, California, August 17, 1936

Shot near the Palo Verde Valley, an entry point for many migrants heading into California, this image captures the Power family, Jess, Zella, and their son Jesse, farmers in Oklahoma whose livelihood had been destroyed by drought.

Maynard Dixon and Son Daniel, 1925

In 1920 Lange married her first husband, Maynard Dixon (1875–1946), a California-born illustrator and painter whose chief subject was the American West. Their first son, Daniel, was born in 1925. Decades after his mother’s death, Daniel wrote, “She was my demon and my defender, my guide and my goad.”8

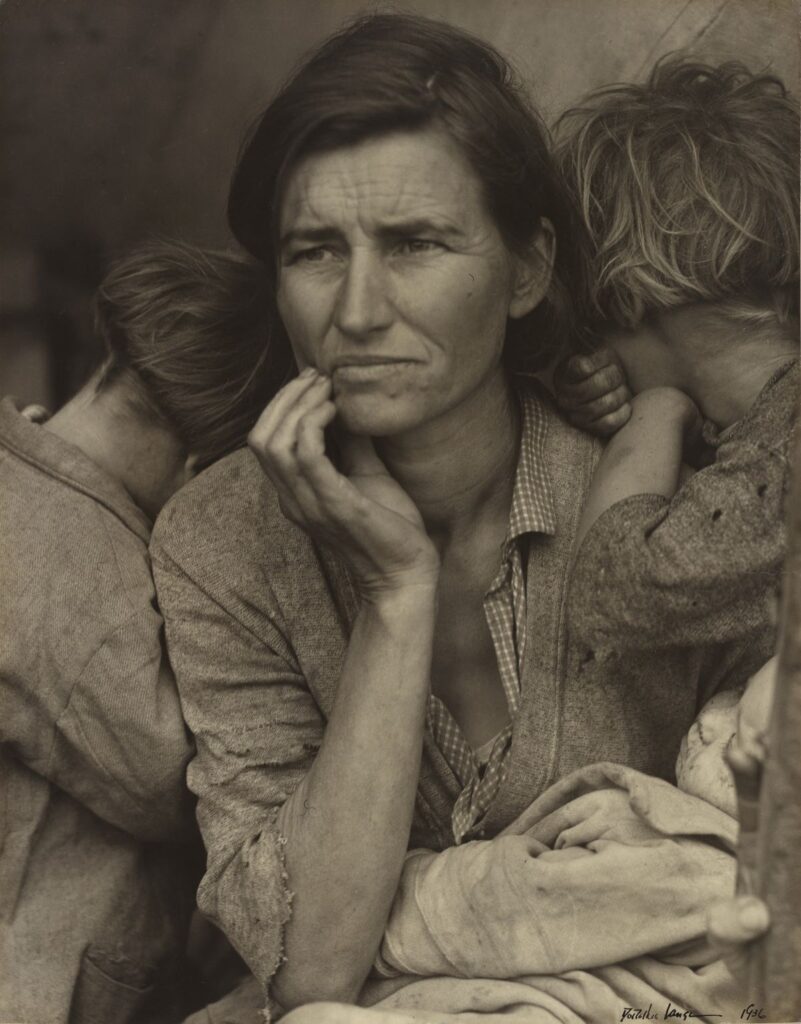

Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother), March 1936

The subject of Lange’s most famous photo is thirty-two-year-old Florence Owens Thompson, a woman of Cherokee descent from Oklahoma. In the mid-1930s Thompson and her family were following the harvest, picking crops in California and Arizona. Not long before Lange took Thompson’s portrait, her family car had broken down, and they took refuge in the encampment for pea-pickers where Lange found them. Thompson told Lange that the family had been living on vegetables foraged from the surrounding fields and birds her children had killed.

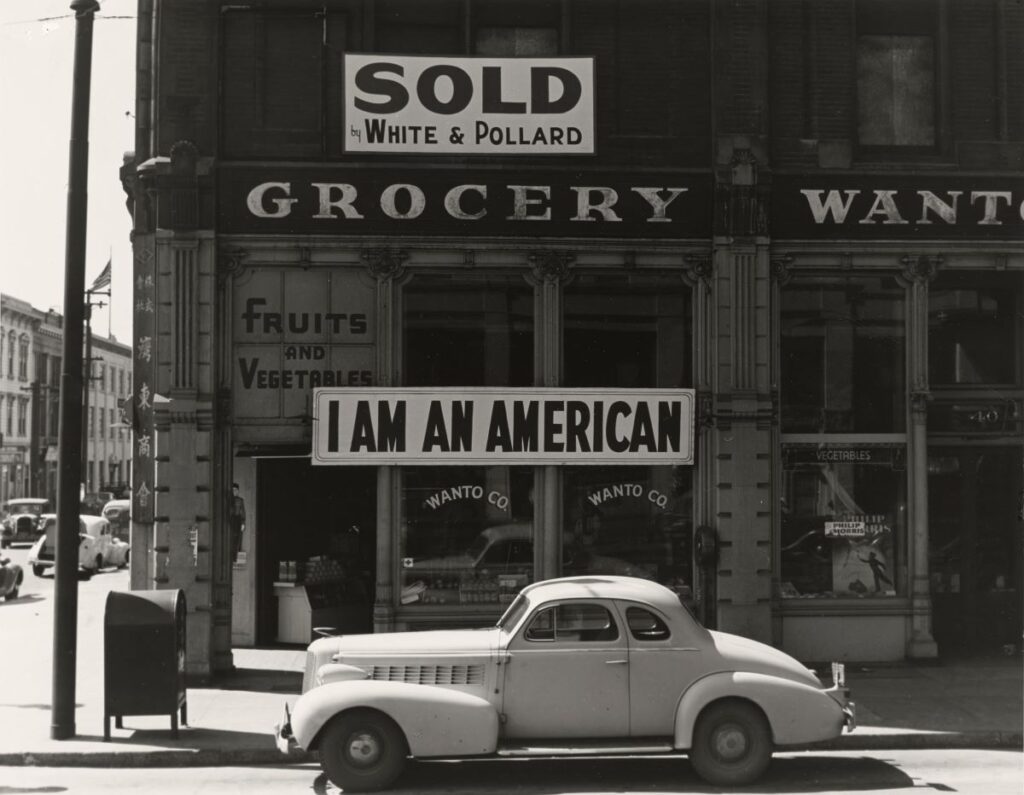

Japanese American–Owned Grocery Store, Oakland, California, March 1942

Tatsuro Masuda, a twenty-five-year-old grocer, posted this large sign on his store the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked. Within weeks, Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent. In 1942 Masada and his pregnant wife were sent to the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona.

Dorothea Lange: Seeing People is on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC through March 31, 2024.

1 Dorothea Lange, quoted in Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1993), p. 144. 2 From an interview of Dorothea Lange conducted May 22, 1964, by Richard Doud, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 Dorothea Lange to Ansel Adams, November 12, 1943, Box 2, Collection 696 (Ansel Adams Papers), Department of Special Collections, University Research Library, University of California Los Angeles. 6 Dorothea Lange, “The Making of a Documentary Photographer,” typescript of an interview conducted in 1960 and 1961 by Suzanne Riess, Berkeley Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1968, p. 149. 7 Quoted in Robert Coles, Dorothea Lange: Photographs of a Lifetime (Millerton, NY: Aperture, 1982), p. 104. 8 Quoted in Dorothea Lange, A Visual Life, ed. Elizabeth Partridge (Washington, DC, and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), p. 162.

THOMAS CONNORS is a Chicago-based arts writer.