Inspired by the archaeological discoveries of the early twentieth century, Marie Zimmermann created extraordinary, and previously unstudied, jewelry in Egyptian and other revival styles.

Marie Zimmermann was among the most eclectic and innovative designers of jewelry and metalwork working in the early twentieth century. Her creations in gold, silver, bronze, copper, and iron explore a wide range of approaches to design, celebrating and interrogating traditional methods and experimenting freely with materials, surface, color, and applied ornament. Because of the diverse and challenging nature of her work, Zimmermann’s oeuvre has received little scholarly attention until now.

The daughter of Swiss immigrant parents, Zimmermann grew up in Brooklyn and was educated at the Packer Collegiate Institute, the Art Students League, and Pratt Institute. She lived for some twenty-five years at the National Arts Club in New York City, where she also exhibited her work alongside that of other leaders of modern American design. Like many designers, Zimmermann’s earliest artistic expression was jewelry, which she continued to produce throughout her career, excelling particularly in intricate combinations of semiprecious stones, delicate enameling, and gold that boldly invoke and subvert Egyptian and classical revival styles.

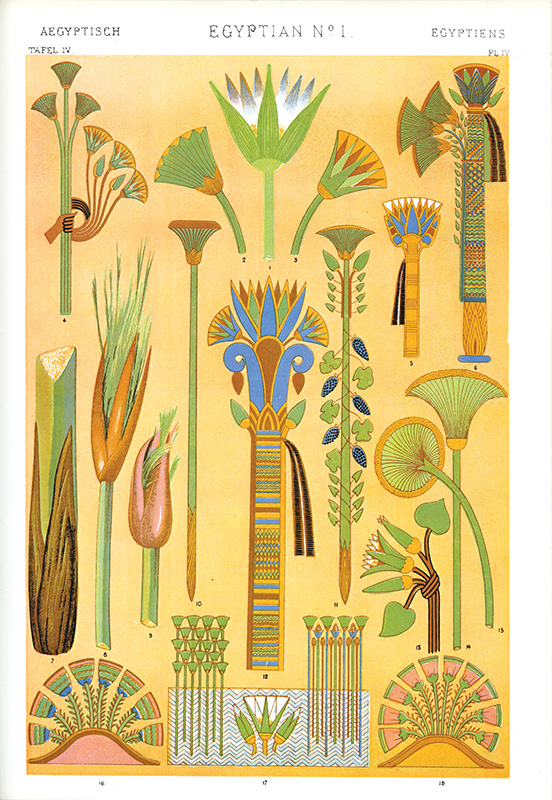

There were two periods of extreme popularity for reinterpretations of ancient Egyptian design in Europe and the United States. The first began in the 1860s and reached international proportions around 1870, inspired by the opening of the Suez Canal. Excavations, World’s Fair displays, and the importation of ancient objects, along with design manuals incorporating Egyptian motifs, from Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament of 1856 (see Fig. 3) to Christopher Dresser’s 1873 Principles of Decorative Design, furthered interest through about 1900.1

The second major wave of the Egyptian revival came with major excavations in the first quarter of the twentieth century-by the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum-leading to the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922. Art and artifacts, including jewelry, from the excavations were swiftly incorporated into museum collections. Exhibitions held at institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum, that museum’s momentous acquisitions of Egyptian material, and the building of a remarkable Egyptian collection at the Brooklyn Museum had a profound effect on Zimmermann.2

She was not the only jeweler to be inspired by the aesthetic these objects represented. Louis C. Tiffany’s first Egyptian revival designs date from about 1900; his jade and amethyst bib necklace made a triumphal showing at the 1906 Paris Salon.3 Then, after a trip to Egypt in 1908, he collaborated with Julia Munson on a line of Egyptian revival jewelry to be sold by Tiffany and Company. In the 1920s Cartier in Paris created a similarly robust line of Egyptian revival works, which Zimmermann could have seen in their New York shop, opened in 1909.4 And many other jewelers also embraced the Egyptian revival, especially with the advent of art deco.5

One of Zimmermann’s most successful Egyptian revival designs is a striking gold ring (Fig. 4) with a clear kinship to bracelets found on Tutankhamun’s arms.6 The ring comprises a beryl scarab in a collet setting and, on the band, three blue and green enamel lines crossbanded by three red enamel lines, a design that evokes both classical columnar forms and the bundles of lotus stems or papyrus reeds often depicted in Egyptian art and artifacts. Flanking this motif, Zimmermann added small half-circles, which may represent the volutes on an Ionic capital, and above, an inverted gold volute set in a pool of rich blue enamel. All of this leads up the sides of the ring to the scarab, whose associations with the creator god Atum stemmed from ancient Egyptians’ belief that young scarab beetles were not hatched from eggs but emerged spontaneously from burrows. The scarab also carried strong solar symbolism and is depicted in many artifacts pushing the sun along its course in the sky. Zimmermann’s ring thus carries themes of miraculous creation and resurrection.

The ring in Figure 5 forges a different pathway with similar success. The stone, a large zircon,7 is set off by eight gold and champlevé enamel prongs shaped as lotus petals, with orange-enameled gold beads punctuating the spaces between them and delicate beads of variegated blue-green secondary hues along the three strands of the flaring gold band. The bold color fields of green and blue enamel evoke ancient royalty, while the striations in the enamel (a technique Zimmermann used often) give it a feathery appearance that recalls various ancient Egyptian sources, including bowl-shaped column capitals decorated with leaf forms and motifs inspired by clustered palm branches from the Old Kingdom through the Roman period.8

Zimmermann created a quite different effect in rings with flat intaglio-cut stones, a popular fashion in jewelry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the example in Figure 6, an intaglio carnelian depicts a classical female figure holding sheaves of wheat, a common ancient symbol of successful harvest, nourishment, and plenty.9 Colorful enameling is applied around the setting, including conventionalized palm leaves at the junctures with the band. In ancient Egypt the palm connoted long life and eternity, but it was a more important symbol for the Romans, to whom it represented success and victory, which Zimmermann may be evoking in a metaphor more consistent with the style and motif of the intaglio.10

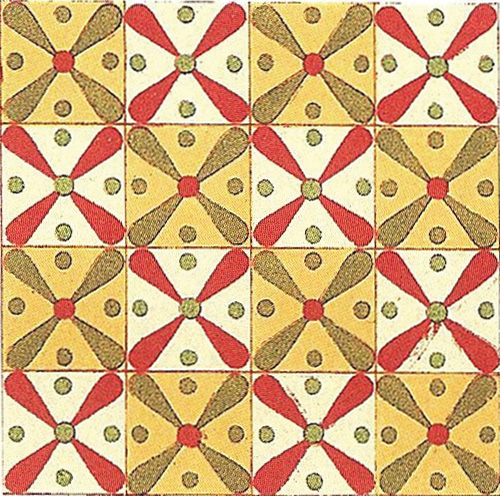

William Burges and other influential jewelry designers in the Victorian period created reproductions and reinterpretations of jewels and settings they admired in old master paintings.11 An old master portrait may have been the inspiration for the overall design of Zimmermann’s superb choker necklace in Figure 7, but the palette and enameled motifs are thoroughly Egyptian. Pearls are set into cups enameled as exquisite lotus forms; even more striking is the enameled design on the outsides and bottoms of the oblong gemstone settings-an X-shaped motif with a small circle in its center that is remarkably similar to patterns in paintings and textiles found in Egyptian tombs, as pictured in Jones’s Grammar of Ornament (see Fig. 8). The angled facets of the gems unite seamlessly with the triangular enamel sections within the trapezoidal links. In turn, these studies in geometry connect serially to the pearls, which subvert the linearity of the scheme with their spheroid forms. Drawing on diverse inspirations and utilizing a bold system of rigid lines and sinuous arcs, Zimmermann’s choker defies easy categorization while retaining a sense of mystery and allure.

For the lovely bracelet in Figure 9 Zimmermann combined Egyptian motifs and art deco style in an unusual overall design. Though in her typical green, blue, and red palette, the irregular shapes of the central gemstones-a low-grade emerald, carnelian, and lapis lazuli-are atypical of her work, or of work by most other American jewelers of the period. The tubes of malachite and enameled gold strung on doubled silk cord create a smooth modernist surface also seen, for instance, in some Cartier designs, and perhaps reflecting the influence of the invention of Bakelite around 1907 and its subsequent use in decorative arts, including jewelry. Cartier incorporated Bakelite in some of its jewelry, but also achieved similar effects with enamel, turquoise, coral, onyx, and other semiprecious materials.12

The reverse of Zimmermann’s bracelet is equally stunning, enameled with Egyptian motifs likely taken from The Grammar of Ornament or from Egyptian works that Zimmermann saw in museums (Fig. 9a). Those on the ends depict a palm leaf spray typical of decorated columns in ancient Egypt, inset with stylized lotus blossoms, while the ornament on the three central settings is again reminiscent of patterns taken from paintings and textiles found in Egyptian tombs as shown by Jones. The brilliant blue enamel fans at the corners recall the geometric formations of scalloped Egyptian columns and various patterns from painted and woven designs.

One of Zimmermann’s most beautiful pieces of revivalist jewelry is an Etruscan style necklace of gold-wrapped wire with shattuckite pendants and coral beads (Fig. 10).13 It recalls settings of Favrile glass beetles by Louis C. Tiffany, though the form of Zimmermann’s necklace is closer to ancient Etruscan precedents than to Tiffany’s Egypt.14 She was almost certainly aware of the famed Etruscan revival jewelry made by Castellani and Giuliano in Rome, which adorned the necks and wrists of leading figures in art and literature, politics and industry, aristocracy and royalty.15 Zimmermann’s design is of uncommon restraint and uncompromising refinement. Its contrasts of blue and orange are subtle and controlled; its rhythms of alternating large and small ovals, beading, and gold rope filigree are elegant and effective. The necklace stands as one of Zimmermann’s greatest accomplishments, combining historicist and forward-looking impulses in a unified work of art.

Zimmermann’s eye-popping brooch in Figure 12 was included in the National Arts Club exhibition in 1928, and was worn by her friend Dr. Connie Myers Guion in a portrait photograph taken in the 1940s.16 The design succeeds in dramatic style, presenting the subtly contrasting hues of black opal and azurite/malachite in one pair of opposing quarters and shattuckite in the other two; the borders are in her signature Egyptian revival palette, but here presented in tourmalines, small emeralds, and blue and pink sapphires rather than enamel. The polychromy calls to mind necklaces with theatrical settings of large alexandrites, sapphires, emeralds, and black opals that Tiffany and Company offered in the 1920s and 1930s. The shape, color, and textures of the black opals as well as the palette of the other stones, and the way in which both pieces invoke a sense of exoticism, relate the brooch to a Louis C. Tiffany pendant of around 1915 to 1920 in which Australian opals, sapphires, topaz, demantoid garnets, pearls, and chrysoberyl are set in gold in an astonishing frenzy of color and alluring motifs suggestive of the ancient jewels of India.17 There is perhaps an even closer connection between Zimmermann’s brooch and a gold and enameled Tiffany and Company one set with deep blue opals, designed by Meta Overbeck and likely created under Louis C. Tiffany’s direction.18

One of the pinnacles of Zimmermann’s achievements in jewelry is the bracelet in Figure 11, in which multifarious sapphires are united with enameled decoration. The shield shape and tapering form may relate to earlier English models, as well as to some made in New York, such as an 1890s Tiffany and Company gold brooch set with zircons, sapphires, and enamel.19 Indeed, Tiffany and Company sold brooches of similar design and composition throughout the late nineteenth century: at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, the firm showed a “fancy” brooch composed of eleven variously colored sapphires set in gold scrollwork and with a pendant, as well as a ring designed by G. Paulding Farnham with a similar palette of diamonds and sapphires; at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 it presented a brooch of “fancy American sapphires,” diamonds, and enamel.20 In addition, among Louis C. Tiffany’s creations is a brilliantly colored necklace of emeralds, fire opals, and blue and pink sapphires made around 1918.21 The glamour and drama of Tiffany objects like these may well have enticed Zimmermann toward a similar aesthetic of radiant luxury.

The bracelet also incorporates Zimmermann’s more familiar Egyptian motifs, most specifically the conventionalized palm or lotus ornament at the two ends of the clasp, this time with a dramatic red central leaf. The large oblong sapphire in the center is secured at its four corners with flaring fans that resembles those in rich blue enamel on the reverse of the bracelet in Figure 9 (see Fig. 9a). The fan form is divided into sections of blue, green, red, and white enamel to strikingly rich effect, similar to the scalloping and other devices in Egyptian columns and painted and woven patterns.

Zimmermann’s jewelry is truly a distinctive body of work. Her childhood during America’s Gilded Age, her training during the heyday of the arts and crafts movement, and her keen awareness of international and historical precedents equipped her to create eclectic and individualistic designs. While jewelry played a particularly important role in her earliest artistic expressions, she continued to create in this medium throughout her career.22 Similarly, her profound interest in Egyptian antiquities and reinterpreting this style was not limited to jewelry or to her early career. She explored innovative uses for this imagery in ironwork, bronze, gilded vases, and, particularly, in her celebrated Egyptian Box, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In all her creations, Zimmermann expressed a personal vision of beauty.

1 At the same time, the firm of Castellani and Giuliano in Rome was marketing an influential line of Egyptian revival jewelry, mostly to European clients. From the mid-nineteenth century on the Castellani name was virtually synonymous throughout Europe with revivalist archaeological jewelry. For a detailed history of the firm, see Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry, ed. Susan Weber Soros and Stefanie Walker (Yale University Press, NewHaven, 2004). 2 For detailed histories of the development of the collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum, see the those museums’ websites. For more about Zimmermann’s exposure to the exhibitions and collections at the museums, see Deborah Dependahl Waters, Joseph Cunningham, and Bruce Barnes, The Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmermann (American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation, New York, and Yale University Press, New Haven, 2011), pp. 7, 31-32, 144, 184-186, 190, 197, 203, 235, 240, 325. 3 John Loring, Louis Comfort Tiffany at Tiffany and Co. (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 2002), p. 41. 4 For more about the firm, see Hans Nadelhoffer, Cartier (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 2007). 5 For examples, see Paul Atterbury and John Benjamin, Arts and Crafts to Art Deco: The Jewellery and Silver of H. G. Murphy (Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, 2005), especially two pairs of earrings shown on p. 59 and the covered bowl shown on p. 74. 6 Illustrated in Clare Phillips, Jewelry from Antiquity to the Present (Thames and Hudson, New York, 1996), p. 8, fig. 6. 7 Based on refractory analysis conducted by gemologist John J. Bradshaw on May 26, 2010, the stone is likely zircon. 8 See, for example, Émile Prisse d’Avennes, Histoire de l’art Égyptien, d’aprés les monuments, depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu’à la domination romaine (Paris, 1878-1879), reprinted as Atlas of Egyptian Art (Zeitouna, Cairo, 1997), pp. 26, 27. 9 Although scientific testing is not practicable, Bradshaw’s gemological analysis determined that the stone is almost certainly carnelian. 10 For more on cameos and intaglios see Sabine Albersmeier, Bedazzled: 5,000 Years of Jewelry-The Walters Art Museum (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2005), p. 56. 11 Charlotte Gere and Geoffrey C. Munn, Artists’ Jewelry: Pre-Raphaelite to Arts and Crafts (Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, 1989), pp. 96-103. 12 For examples, see Cartier 1899-1949: The Journey of a Style, ed. Nuno Vassallo e Silva and João Carvalho Dias (Skira, Milan, 2007), pls. 102, 104, 105; Nadelhoffer, Cartier, pls. 146, 147. 13 Scientific testing of these elements was not practicable, but the stones are very likely shattuckite and the beads are likely coral. Bradshaw, gemological analysis. 14 See, for example, Janet Zapata, The Jewelry and Enamels of Louis Comfort Tiffany (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1993), pp. 114, 115. 15 For example, see a necklace of gold and Sardinian pearls, part of a parure made by Castellani and Giuliano, now in the Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome, and illustrated in Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry, p. 272. It does not seem that Castellani and Giuliano ever had a shop or any significant point of distribution in New York, and there were no major exhibitions of their work in the United States. Still, they were extremely well known during the second half of the nineteenth century and sold many works to wealthy Americans and Europeans. 16 This is likely the “black opal & jewel brooch,” priced at $800, at the National Arts Club exhibition in 1928. Marie Zimmermann, duplicate entry slip for National Arts Club Exhibition of the Decorative Arts, March 1928, National Arts Club Papers, Archives of American Art microfilm roll 4245, frames 97-101. The photograph is in the Connie Guion MD Papers, Medical Center Archives of New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell; illustrated in Waters, Cunningham, and Barnes, Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmermann, p. 166. 17 The pendant, in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, is illustrated in Stephen Harrison, Emmanuel Ducamp, and Jeannine Falino, Artistic Luxury: Fabergé, Tiffany, Lalique (Cleveland Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 2008), p. 272. 18 Ibid., p. 310. 19 For illustration, see Clare Phillips, Bejewelled by Tiffany (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2006), p. 173. 20 For illustrations see ibid. 21 For illustration, see Loring, Louis Comfort Tiffany at Tiffany, p. 64. 22 See Waters, Cunningham, and Barnes, Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmermann, p. 159.

JOSEPH CUNNINGHAM is the curatorial director of the American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation and a coauthor of The Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmermann (Yale University Press, 2011).