Glenn Adamson: Perhaps we could begin with your own history at the American Wing. Is there some way you could summarize what’s been happening in the time that you’ve been there?

Sylvia Yount: I arrived in fall 2014, so I’m coming up on my tenth anniversary. Already then we were beginning to expand the narratives we tell in the galleries and the collections we were looking to build. For example, the year before I arrived, Ronda Kasl had been hired as the Met’s first curator of Latin American art, so we were thinking hemispherically, and critically, about what it means to depart from the British-American focus that shaped the wing’s collection from the time of our founding, in 1924, and continued, arguably, up to the 1980s. So, that was a starting point—questioning the claim that the American Wing held the most comprehensive collection of American art. But how can any collection ever be truly comprehensive? What did that claim mean? If we wanted to stand by it, we needed to broaden the scope of what we were doing.

A major step in that direction was the announcement of the promised gift of the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of historical Native American art in Spring 2017 (Fig. 11).

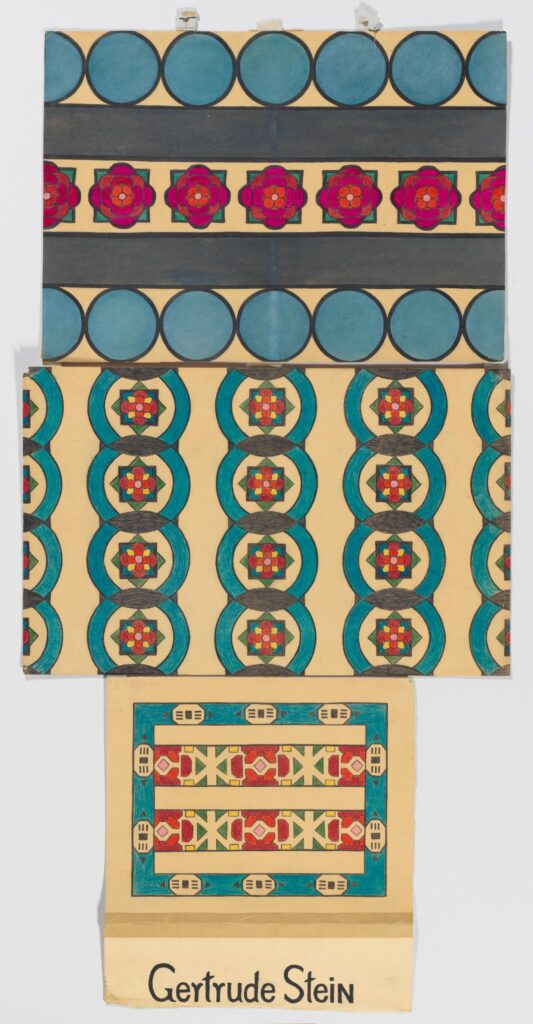

No question. We knew that would radically expand the stories we could tell. Also, since the Native American material would need to be rotated on an ongoing basis—not least because of light sensitivity––it was clear there should be a dialogue between past and present, looking at the continuity of historical traditions in work by modern and contemporary Indigenous artists. With the appointment in 2020 of Patricia Marroquin Norby, the Met’s first-ever curator of Native American art, we’ve been acquiring more contemporary works, many by Native women. We’re also excited about an exhibition this summer of the recently acquired 1920s–1940s art of Mary Sully, the all-but-unknown Dakota modernist that readers of The Magazine ANTIQUES will remember from the great piece that Elizabeth Pochoda wrote in 2020 [“The Unexpected Art of Mary Sully,” January/February 2020; Fig. 5]

More generally, allocating the Wolf Galleries to Native American material has allowed us to see our collections in the American Wing in greater relation to others across the Met. Our previous director, Tom Campbell, felt strongly about working cross-departmentally, and that has continued under Max Hollein. A good example would be Ronda’s work exploring Latin American colonial networks, as a global context for japanned and other eighteenth-century decorative arts in our collection.

What about changing installations within the American Wing itself?

Well, we’re not moving the Emanuel Leutze [Washington Crossing the Delaware; Fig. 3]! That is a question I often get. But juxtaposing it with other resonant works by a range of artists—for example, as we did last year with Kara Walker and Robert Colescott (Fig. 4)—presents opportunities to view that icon in a fresh light. Those are the kinds of dialogues that we can create, bringing different voices into the conversation. We’re also reinstalling the galleries on the second floor as part of the 2024 project, as well as creating proper introductory spaces on the first floor that will welcome visitors to the American Wing and explain our history and evolution through a range of multilayered works selected from across our varied collection.

The American Wing has a somewhat arbitrarily defined chronology—historically, the collection includes no “fine” arts made by artists born after 1876; and no “decorative” arts produced after roughly 1920. How are you approaching the issue of chronology in the reinstalled galleries?

We’ve all been schooled, traditionally, to see a difference between “American art” and “modern art”—that is how the canon has been shaped. Many museums are rethinking that. It’s challenging here because our modern and contemporary galleries are on the opposite side of the building from the American Wing. So, what we’ve done up to now is to borrow from our colleagues strategically, and place relevant historical and modern works in conversation. We’d like to do more of that going forward, and we do have an opportunity—when the modern and contemporary galleries begin to close in preparation for the new Tang Wing—to produce more focused installations of a broadly conceived “modernism.” We’ll also be looking closely at the decade of the 1920s, when the American Wing was founded—a time of great social change and contradiction that defined what many of us think of as modernist culture. Yet it was also an age of revivalism, which is a key part of our inheritance in the wing.

Are you also bringing new approaches to the decorative arts—the period rooms, the historic furniture?

The American Wing was founded around those collections, and they remain central and valued. However, we want to present them in different ways in 2024. We will still have the contextual displays in the period rooms, but in other galleries we are taking a more minimalist approach, highlighting the artistry, the materiality, the sculptural quality of furniture and other decorative arts. I think these new installations—overseen by Alyce Perry Englund, associate curator of American decorative arts—will be surprising for a lot of people. As to the period rooms, the project we did with the Costume Institute in 2022 [In America: An Anthology of Fashion; Fig. 6] as well as the example of the museum’s Afrofuturist period room, opened our minds to what more we can do in terms of display and interpretation of those historical spaces, including in digital form.

Getting back to the anniversary itself, how are you communicating its significance? It’s such an important milestone, but we necessarily look back at that foundational moment with complicated feelings.

Yes, you’re right. In one sense, the American Wing was innovative for its time—that so-called German method of displaying decorative arts, anchored in period rooms, which was aimed at the acculturation of new immigrant classes in New York, teaching them American history. But, of course, it was also a case study of colonial revival ancestor worship. And, you know, it’s really provocative to revisit now—as we’re experiencing echoes of the 1920s with issues of immigration and nativism, among other challenges. It does make you think critically about what the goals were at the beginning of the American Wing, and where we are now. And I think it’s our responsibility as curators to tell more nuanced stories about our past, regarding our culture at large as well as in terms of the American Wing—for example, the surprisingly diverse tastes of our founders, Emily Johnston de Forest and Robert de Forest, who made space for the arts of both British America and Mexico in their vision for the department. And we’ll be furthering some of the thinking from the last major renovation in 2012, introducing more thematic galleries like the one on the Civil War and Reconstruction (Fig. 8); doing more with folk art; and, certainly, integrating more seamlessly Latin American and Native American art. We need to make a clear statement about why that work belongs in the American Wing.

It’s almost like the anniversary allows you to throw all these recent developments into higher relief.

This work has been going on for some time, and it’s never really finished. So many visitors see museums as beacons of enlightenment and authority, but, in fact, it’s always evolving, all the time. We have to consider multiple perspectives in our interpretive strategies, for example, around a recent acquisition like Bélizaire and the Frey Children [see Endnotes, “A Portrait and a Personal History Revealed,” September/October 2022; Fig. 9]. It’s not just going to be a curatorial voice in that label. It’s also the collector, the conservator, the historian from New Orleans. We need to strike the right balance between those different voices without overwhelming visitors with too much text on the wall, and still let the objects speak.

I suppose what you’re doing is akin not only to other recent American art reinstallations, like those in Philadelphia and Boston, but also MoMA’s reopening in 2019, in which they were obliged to rethink the story of modernism—which is, of course, their own story. One last question, of a more speculative nature: what do you think the American Wing might look like in another hundred years?

Great question. Will we even have chronologies, any dividing line between historical American art and what we now consider modern and contemporary? Will we still have medium-based departments, works on paper versus paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts? Will people care about the eighteenth century? I’d like to think that there will still be a love of history, an interest in learning about the American past in all of its complexity. Certainly, more artists will be discovered and come to the fore. Maybe there won’t even be a canon anymore. But one thing I can almost guarantee: in this future constellation, the Leutze will likely still be in the galleries of the Met somewhere!