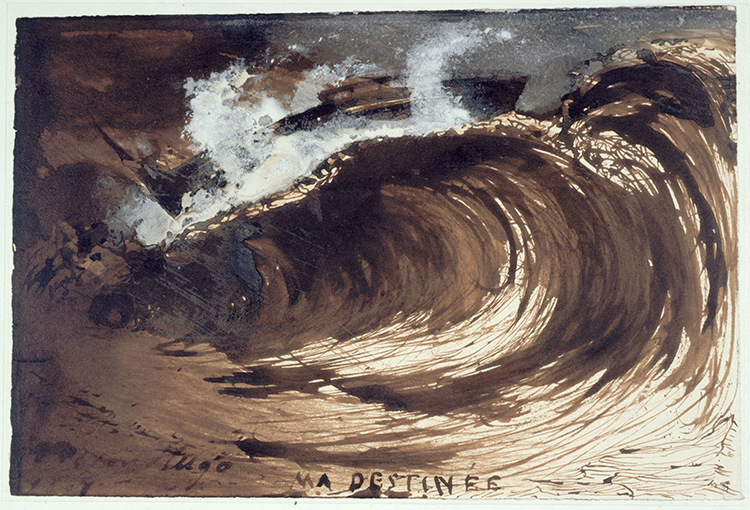

Ma destinée [My Destiny] by Victor Hugo (1802–1885), 1867. All objects illustrated are in the collection of the Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris/Guernesey; photographs courtesy of the Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris/Guernesey and Roger-Viollet, Paris.

Many famous writers liked to draw, but the impulse to cast them as artistic as well as literary savants is usually best resisted. Lemma Press’s recent catalogue raisonné of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s doodles provides a case in point: the depictions of his characters and acquaintances, of ogee arches and other architectural elements charmingly point to the Russian writer’s preoccupations, but they’re bagatelles; most of them were scribbled in the margins of his notebooks. It’s quite a different story, however, with regard to Victor Hugo. The author of Les Misérables showed surprising fluency with graphic conventions in the ink, wash, graphite, and charcoal drawings that make up his striking—and psychologically illuminating—body of work. Stones to Stains: The Drawings of Victor Hugo at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles shines a light on sixty-four drawings selected from the more than three thousand sheets of illustrations that Hugo left to the world.

Le phare des Casquets [The Casquets Lighthouse], 1866.

Many of the French writer’s drawings are full of sound and fury, and they signify plenty. The writer’s days were darkened by the deaths of four of his five children (one daughter drowning in the Seine) and the depressing rise of Napoleon III’s Second Empire, a shock to his Republican constitution that precipitated his self-exile to the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey. Stranded, as it were, on these lonely outposts for nearly twenty years, Hugo took up pen and brush to produce nighttime views of lonely, bluff-surmounting citadels and lighthouses, and of ships lashed by gale-force winds, almost swallowed in a haze of brown wash. Occasionally he deciphered the meaning of these works: an enormous crashing wave from 1867 is helpfully inscribed “ma destinée.”—my destiny.

If these storm scenes flirt with melodrama—the bane of all romantic artists and writers—they’re balanced by playfulness. Hugo participated in séances between 1853 and 1855, and was fond of conjuring fire-breathing serpents or leering sea dogs from shapes he saw in inkblots. He was an experimenter, deriving compositions through processes of folding, blotting, stencil-cutting, and soaking. His son Charles recalled that his father would round off laboriously drafted tableaus “with a light shower of black coffee,” an act of cheerful abandon that demonstrated the faith of the writer—who was, incidentally, devout—in outcomes left to God.

Ecce Lex (Le pendu) [Behold the Law (Hanged Man)], 1854.

Despite earning praise for his artistic prowess from the likes of Delacroix and Baudelaire, Hugo downplayed the significance of his drawings, and they weren’t publicly exhibited until three years after his death. But he did allow reproductions to be made, first by his brother-in-law, and then, more successfully, by the wood engraver Fortune-Louis Meaulle. The most recognizable reproduction is probably the heliogravure John Brown, 1861, a somber image of the hanged American abolitionist. But there’s always something that gets lost in translation, which is why it’s satisfying to see that the original—an 1854 drawing with lighter lights and darker darks, made in response to the execution of a Guernsey criminal—and not the print, is hanging at the Hammer.

Stones to Stains: The Drawings of Victor Hugo • Hammer Museum, UCLA, California • to December 30 • hammer.ucla.edu

Share: