Late last year, I happened upon an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art that appeared so out of context it stopped me cold—and ultimately changed my understanding of the early history of our nation.

The surprise was a display on the museum’s fifth floor depicting the interior of the front parlor of Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Virginia home. The room’s paneled walls boast a pair of gilded oval mirrors; blue silk and wool damask curtains hang at the side. Between the mirrors is Jean-Antoine Houdon’s clay bust of Washington, which the artist gave the president-to-be after visiting Mount Vernon in 1785.

An iPad near the display instructed the visitor to view the Houdon bust with it. When I did, I experienced a work of augmented reality (AR). On the screen, super-imposed on the bust, were colorful videos of colonial-era maps of upstate New York. At first it looked cheerful. Then you learn the places on the maps were Native American settlements in rural New York that were destroyed, on Washington’s explicit orders, in 1779.

The work is part of Wolf Nation, a four-part exhibition created by Alan Michelson, a New York-based artist and Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. (Michelson was helped by artist and digital developer artist Steven Fragale.) Michelson’s work introduces the history of Native Americans during the Revolutionary War, using video, sound, print, and AR to reveal forgotten layers of the past.

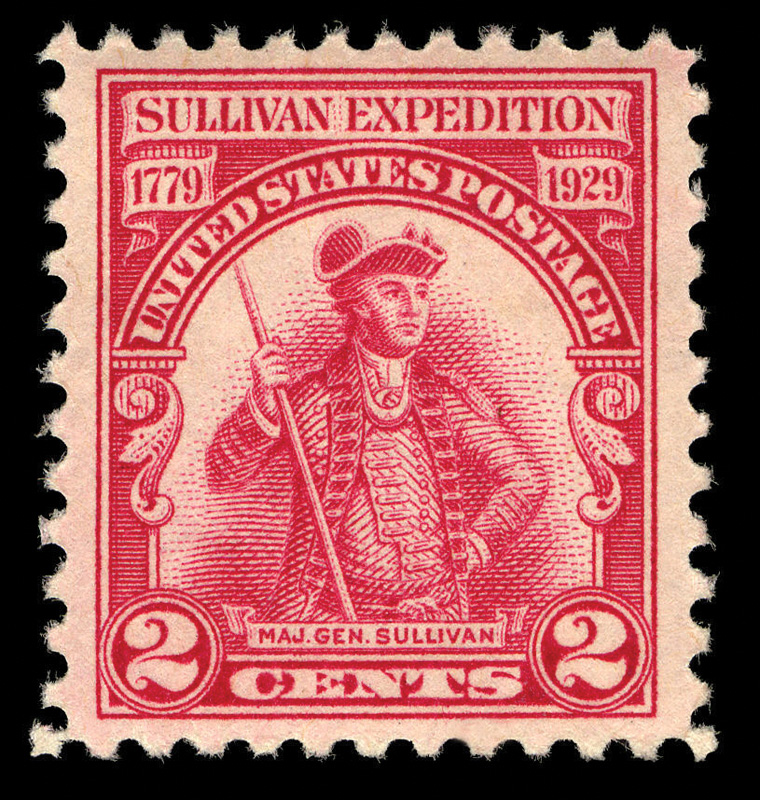

Washington decided to remove the Iroquois from their hunting grounds and farms after they had teamed up with the British to ravage a colonial settlement in Cherry Valley, New York. He ordered General John Sullivan and some four thousand soldiers to undertake “the total destruction and devastation” of Iroquois settlements in upstate New York and the Susquehanna Valley in Pennsylvania. The Sullivan Expedition, launched in June 1779, burned and plundered nearly sixty native villages and 160,000 bushels of crops. It forced five thousand terrified Iroquois to retreat to Fort Niagara in British Canada, where many died of starvation that winter. The Native American name for Washington, “Town Destroyer,” is the title of the AR piece. “Thousands and thousands of acres of vegetation and cornfields burned,” Michelson says. “The campaign was a genocidal act that destroyed the Iroquois’ ability to live on their own lands. They were weakened and doomed.” Recalling that Native Americans have occupied North America for more than ten thousand years, Michelson questions how colonists, “strangers coming to a new place where they had no roots, assumed they could take it all over and keep their self-image as moral people.”

This point of view was new to me. In fact, the story of colonial America I was taught, as an eleven-year-old in boarding school in Deerfield, Massachusetts, was quite the opposite. I was told about the terrible Deerfield Massacre of 1704, when fifty French soldiers from Quebec and their allies, two hundred or more Native Americans, raided the village, killing forty residents and burning seventeen of the forty-one houses one February dawn. They took 109 people captive (to ransom them) and marched them through heavy snow over hundreds of miles to Montreal.

As kids we were mesmerized by the many firsthand accounts the captives wrote. I lived in a dorm that was one of the houses the English put up when they rebuilt the village. In my imagination, I was living in colonial times. We were also taken to Historic Deerfield’s house museums, which are furnished with fine colonial antiques, period wallpapers, textiles, early silver, and household goods. Perhaps not surprisingly, as an adult, for years I wrote a newspaper column about antiques. Now, thanks to Michelson, I’ve learned the other side of the story.