Fig. 1. Fighting Cows by Franz Marc (1880–1916), 1911. Oil on canvas, 32 5/8 by 53 1/8 inches. Private collection; photograph by Peter Barritt/Alamy, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Franz Marc and August Macke were both young artists—twenty-nine and twenty-three, respectively—when they first met in Munich in January 1910. Marc was Bavarian and Macke was from the Rhineland. They soon became friends and visited each other’s studios in and near Munich. They shared many affiliations, friends, and interests. Along with artists such as Vasily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, and Paul Klee, both were members of the Blaue Reiter—the loose-knit group of expressionists whose theories on color and abstraction helped shape the course of modern art. Beginning with the first Blaue Reiter show in December 1911, Marc and Macke would exhibit their work together often during their short lifetimes. Tragically, both artists were killed in World War I before they reached middle age or what might have been a mature style of painting. A new exhibition at the Neue Galerie focuses on Marc and Macke’s artistic relationship, how their lives intersected, and how their art was perceived and received during their lifetimes.

Fig. 2. Storm by August Macke (1887–1914), 1911. Signed and dated “A. Macke/ 1911” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 33 1/8 by 44 1/2 inches. Saarland Museum, Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz, Germany; photograph by akg-images.

When they met, neither had been recognized with an exhibition. Marc, however, had been promised a solo show by Josef Brakl, in whose Munich gallery a few of his lithographs could be found in early 1910. A few days after his twenty-third birthday, Macke went to the gallery, together with his cousin Helmuth and his wife Elisabeth’s cousin Bernhard Koehler Jr. (son of the well-known collector). They were so impressed by Marc’s work that they inquired about the artist’s name, obtained his address, and went to meet him that same day.

The encounter would have far-reaching effects from a personal as well as a professional point of view: the four young men became friends, and Elisabeth’s uncle, Bernhard Koehler, would become a major supporter of both Marc and Macke. At the time they met, the younger Bernhard Koehler bought a lithograph, and a sculpture, and arranged for two of Marc’s paintings to be sent to his father in Berlin. Soon thereafter, the eminent collector came to Munich, where he assisted with the installation of Marc’s first exhibition at the Brakl gallery. Certainly, Macke saw Marc’s show, which opened in February and included such works as Siberian Sheepdogs and Interior of Forest with Deer (Fig. 7). These paintings from 1909 feature subdued color. Animals that are included become one with the surrounding landscape. The images of dogs are part of the snowy background; only later would Marc use color to make his white dog stand out against the snow.

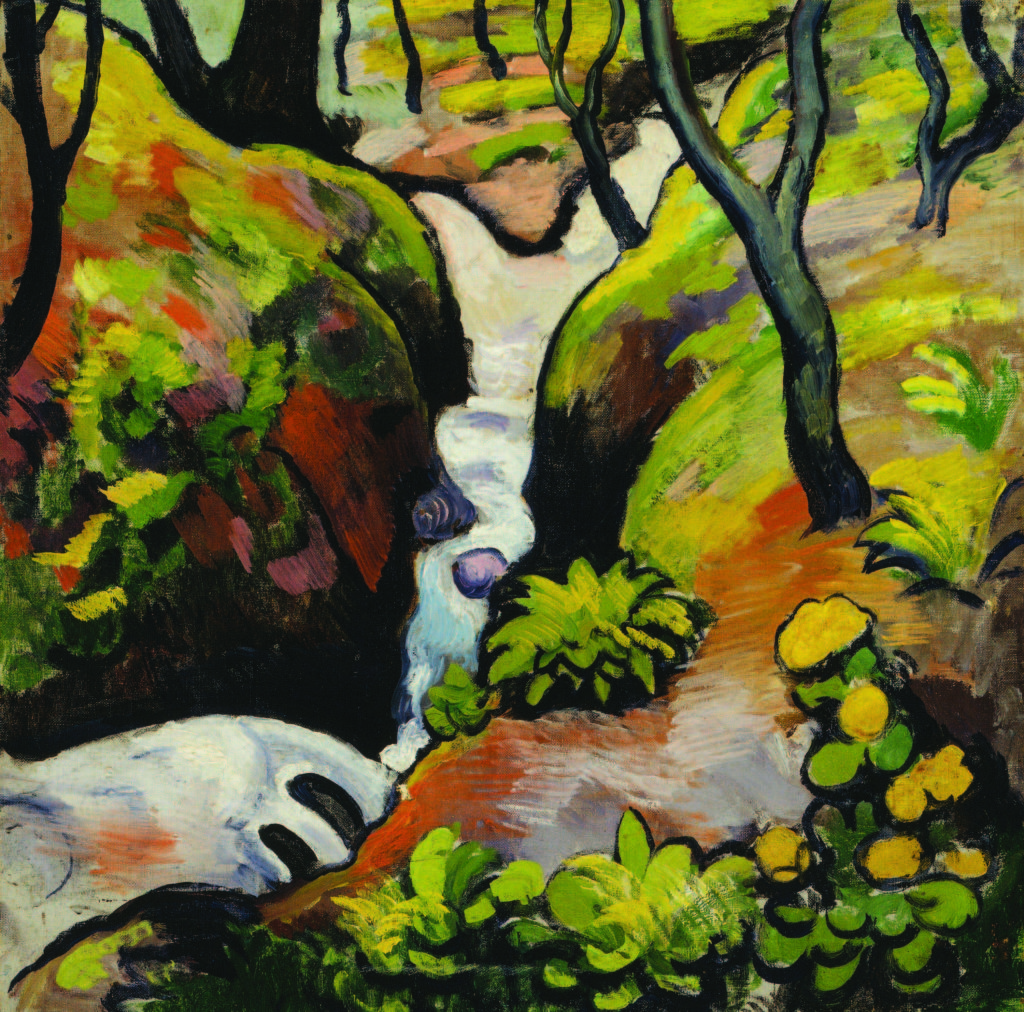

Fig. 3. Forest Walk by Macke, 1913. Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 by 41 1/2 inches. Private collection, photograph © Maurice Aeschimann.

In late January, Marc and Maria Franck (later his wife) visited Macke’s atelier and saw his recent paintings. Among Macke’s favorite pictures he had painted in the late autumn was Portrait with Apples, which shows his bride, Elisabeth, posing serenely while holding a plate of fruit. In her memoirs, Elisabeth Macke described Marc’s first visit and how he appeared: broad-shouldered, with elegant movements, a fur cap on his head, and next to him, like a young polar bear, his dog, Russi.1 The two artists began a lively correspondence. By August, they were using the familiar form of address in their letters and postcards. Maria Marc recalled in her memoirs: “At last help came from outside. [Franz] made the acquaintance of the young painter August Macke, who spoke enthusiastically of Paris, his pictures having been inspired by the young Paris painters. He found Macke’s whole ebullient character refreshing and his youthfully bright pictures delighted him. They were soon closely knit in friendship ….It was the start of a new phase in Franz Marc’s life, one that was to mark the true start of his creative years.”2

Fig. 4. The Wolves (Balkan War) by Marc, 1913. Initialed “M.” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 27 7/8 by 55 inches. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, Charles Clifton, James G. Forsyth and George W. Goodyear Funds.

Fig. 5. Franz Marc in a photograph from 1910. Wikimedia Commons.

For his part, the younger Macke admired his friend’s strength of character as well as his artistic opinions. That he responded to Marc’s

Fig. 6. August Macke in a photograph from 1904. Wikimedia Commons.

paintings is evident in pairing their landscapes: for example, Marc’s Interior of Forest with Deer with Macke’s Forest Stream (Fig. 8). Although the latter differentiates between light and dark and is more colorful than Marc’s forest, the paintings share similarities.

In April 1911 Macke exhibited for the first time in a group show in Bonn, where he had moved. The next month, a show in Munich featured new work by Marc, including Fighting Cows (Fig. 1) and Ape Frieze. The shift toward bolder, nonnaturalistic color is immediately apparent. Fighting Cows contains vivid hues of red, blue, yellow, orange, and green, which recall Marc’s description of colors in a letter to Macke dated December 12, 1910:

Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay, and sensual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy. . . . If you mix red and yellow into orange, you lend the passive and feminine yellow a “virago-like,” sensuous violence so that the cool, spiritual blue, the man, becomes indispensable in turn, and the blue presents itself immediately and automatically next to the orange; the colors love each other, so you awaken to life red, the material, the “earth.”3

The year 1911 marked new friendships, projects, and travels for Marc. At the beginning of the year, he met Kandinsky and joined his group, the New Artists’ Association of Munich. By the summer, he was working closely with Kandinsky editing a book of essays on art, conceived as a yearbook. The volume was published the next year as der Blaue Reiter almanac.

Fig. 7. Interior of Forest with Deer by Marc, 1909. Signed and dated “F. Marc/ 09” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 by 33 inches. Sprengel Museum Hannover, Germany; photograph by Michael Her-ling and Aline Herling/bpkBildagentur/Art Resource.

Both Marc and Macke contributed essays to the almanac, and both had paintings in the now-famous Blaue Reiter exhibition of December 1911. The show resulted from the rejection, of Kandinsky’s Composition V for the third presentation of the New Artists’ Association. Kandinsky, Marc, and others resigned and quickly organized a counter-exhibition that took place at the same time as the New Artists’ show. Marc exhibited The Yellow Cow and Ape Frieze, among other works. One of three paintings by Macke was Storm (Fig. 2), a work that stands out from his other pictures. It reflects the work of Marc as well as Kandinsky in its abstraction and agitation. Parallels have been drawn between Storm and The Yellow Cow. The juxtaposition of yellow and red, the dark vegetation in the foreground, the emphasis on curving yellow shapes, and the boldly abstracted forms in both pictures suggest a dialogue. Given its later significance, the critical response to the show was limited, perhaps because it opened on December 18 and was on view during the Christmas and New Year holidays. A second Blaue Reiter exhibition, subtitled Schwarz-Weiss (Black-White), was held from February to April, in which both Marc and Macke, as well as Kandinsky and Paul Klee, showed works on paper.

Fig. 8. Forest Stream by Macke, 1910. Oil on canvas, 24 1/4 by 24 1/8 inches. Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University Bloomington, partial gift of the Robert Gore Rifkind Collection; photograph by Kevin Montague.

In early January 1912, Macke celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday and began what would be a very active and successful year. His first one-person exhibition took place in April at the Moderne Galerie in Munich. Marc, who had installed the show, wrote to Macke on April 4: “The whole room seems incredibly alive and stimulating; personally, the picture On the Rhine with a Sailboat is essentially my favorite. If it should go unsold later, I would really like to have it.”4 In all, Macke participated in twelve exhibitions and sold many works from the solo shows in Bonn, Cologne, and Jena.

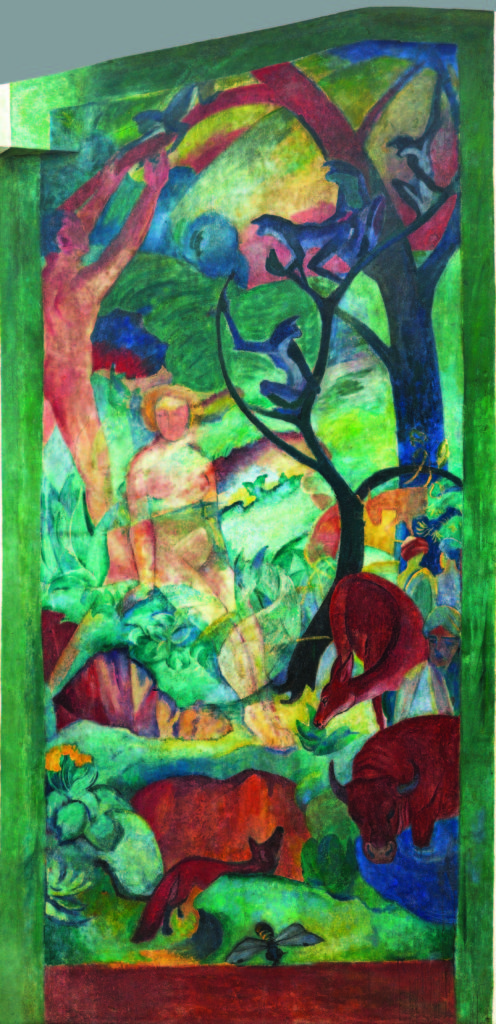

Fig. 9. Paradise by Macke and Marc, 1912. Oil on plaster, 13 by 6 1/2 feet. LWL-Museum f Kunst und Kultur, Mster, Germany; photograph by Sabine Ahlbrand-Dornseif and Hanna Neander.

In September, Macke and Franz and Maria Marc traveled to Paris, where they visited numerous galleries as well as the studios of Henri Le Fauconnier and Robert Delaunay, who had both exhibited earlier in Munich. On their way home, the Marcs stayed with the Mackes in Bonn. Franz and August worked together to paint the large mural Paradise (Fig. 9). Marc’s contribution included Adam, the tree with monkeys, the animals, and much of the landscape whereas Macke is thought to have painted Eve and the four figures in costume at the right of center. More difficult to determine from their collaboration is who conceptualized the overall composition.

As early as April 1913, Marc and Macke had begun to make preparations and compile lists of artists to include in the Erster Deutscher Herbst-salon—First German Autumn Salon, conceived as a Berlin counterpart to the Paris exhibition. Both artists traveled to Berlin to assist with the final selection and installation of the Herbstsalon in early September 1913. Marc showed seven paintings and Macke, eight. In all, 366 works were exhibited: there were twenty-one by Robert Delaunay, twenty-two by Henri Rousseau, and seven by Kandinsky.

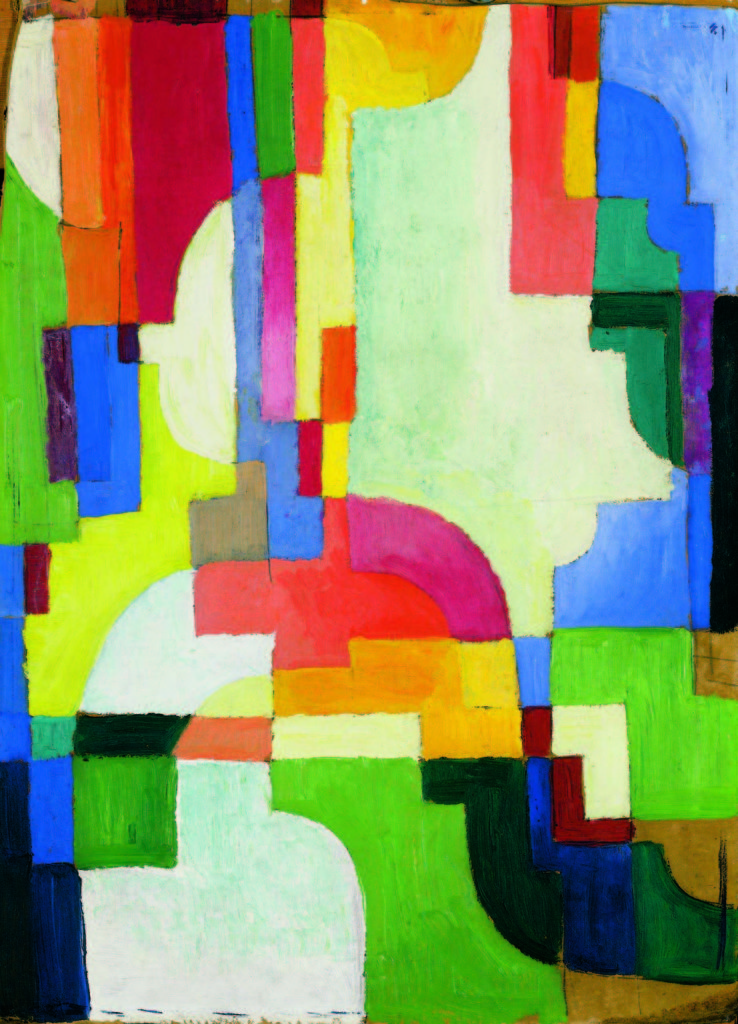

Fig. 10. Colored Forms I by Macke, 1913. Oil on board, 17 3/8 by 12 5/8 feet. LWL-Museum f Kunst und Kultur; photograph by Sabine Ahlbrand-Dornseif.

Among the pictures by Macke were Four Girls and Forest Walk (Fig.3). The works Marc showed included The Wolves (Balkan War) (Fig. 4) and The First Animals. Since the canvas was destroyed, The First Animals is known from an extraordinary watercolor: it presents two pairs of horses against abstract patterns of color suggesting a landscape. The juxtaposition of Marc’s The Wolves (Balkan War) and Macke’s Forest Walk underscores the sense of anxiety and threat the world faced in 1913.

After their stay in Berlin for the Herbstsalon, Marc and Macke never saw each other again. They and their wives wrote letters and often expressed the wish to meet: the Mackes were in Switzerland and the Marcs did not have the money to travel there. Although they did not know each other’s recent work, both artists began to paint in a distinctly abstract style: Macke’s Colored Forms I (Fig. 10) bears the date 1913 and Colored Forms II has been dated to 1913–1914, as has Marc’s Small Composition III.

Fig. 11. Broken Forms by Marc, 1914. Oil on canvas, 44 by 33 1/4 inches. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Marc’s last—probably unfinished—canvases such as Broken Forms (Fig. 11), are remarkably abstract. Macke’s last painting is Farewell (Fig. 12), which his widow said was also called “mobilization” and described thus: “Suddenly everything is gloomy, the lights go out, dull shades of color, the people stand pressed up against one another, still, everything was said to have come over her as something unpreventably terrible, threatening her.”5

Both Marc and Macke joined the German army shortly after the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914. Macke was killed in action on September 26, 1914, just weeks after he left for the front. Hearing of his death, Marc wrote an obituary in late October from Hagéville, where his brigade was stationed: “Anyone who cared about new German art in these recent, eventful years, who had any inkling of our artistic future, knew Macke. And those who worked with him, we, his friends, we knew what a secret future this genial man bore within him. With his death, one of the finest and boldest trajectories of our German artistic development has been rudely curtailed; none of us can continue it.”6 A year and a half later, on March 4, 1916, Marc was killed in combat also on the western front near Braquis at the age of thirty-six.

Fig. 12. Farewell by Macke, 1914. Oil on canvas, 39 . by 51 3/8 inches. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany; photograph © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Kn.

1 Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke, Erinnerung an August Macke (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1962), p. 144. 2 Translation from Annegret Hoberg, “August Macke and Franz Marc: Ideas for a Renewal of Painting” in August Macke and Franz Marc: An Artist Friendship, ed. Volker Adolphs and Annegret Hoberg, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Bonn and Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2014), p. 21. 3 August Macke-Franz Marc: Briefwechsel, ed. Wolfgang Macke (Cologne: DuMont Schauberg, 1964), p. 28. 4 Ibid. p. 114. The painting with sailboat has not been identified. 5 Erdmann–Macke, Erinnerung an August Macke p. 245. 6 English translation from August Macke and Franz Marc: An Artist Friendship, 2014, p. 315.

This article is excerpted and adapted from the catalogue for the exhibition Franz Marc and August Macke: 1909–1914, on view at the Neue Galerie in New York through January 21, 2019. Unless otherwise indicated, original German passages translated by Steven Lindberg.

VIVIAN ENDICOTT BARNETT is an independent art historian, curator, and author of numerous publications on Vasily Kandinsky and the Blaue Reiter. She compiled four volumes of the Kandinsky catalogue raisonné and organized the Alexei Jawlensky retrospective presented at the Neue Galerie in 2017.