Tow Cleopatra’s Needle from Alexandria to London with thread? Look for real estate in a Sphinx-shaped building? Dream about barging down the Nile in your Maidenform bra? These are just a tiny hint at the ways ancient Egypt has sparked the imaginations of European and American consumers from as early as the eighteenth century. For an entertaining and enlightening look at the phenomenon, visit the thirteen hundred posts on Matthew Bird’s (@pasigraphy) Egyptian Revival Instagram lecture. We asked Bird, a multi-faceted designer and curator, and recently retired professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, to tell us more.

How did you come up with the idea for the posts?

Really, it was a bit of a tool to preserve my sanity as I struggled through another Covid semester teaching college sophomores, who were as inscrutable to me as I must be to them. So focusing on 3000 bc seemed like a good tactic. I had seen a Castellani necklace at Sotheby’s in New York that didn’t match my understanding of Egyptian revival styles, so I decided to do some research and learn more. I came to realize that there is really no one “Egyptian revival”—it’s an ongoing thing that has informed architecture, fine and decorative arts, and design since at least about 1780, when Wedgwood and Bentley made its Canopic jar.

Can you tell us about some aspect that particularly surprised or delighted you?

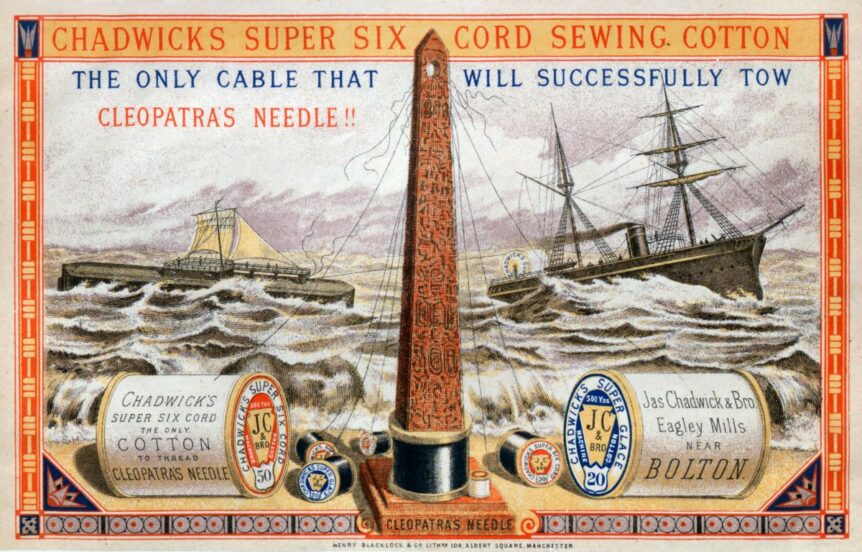

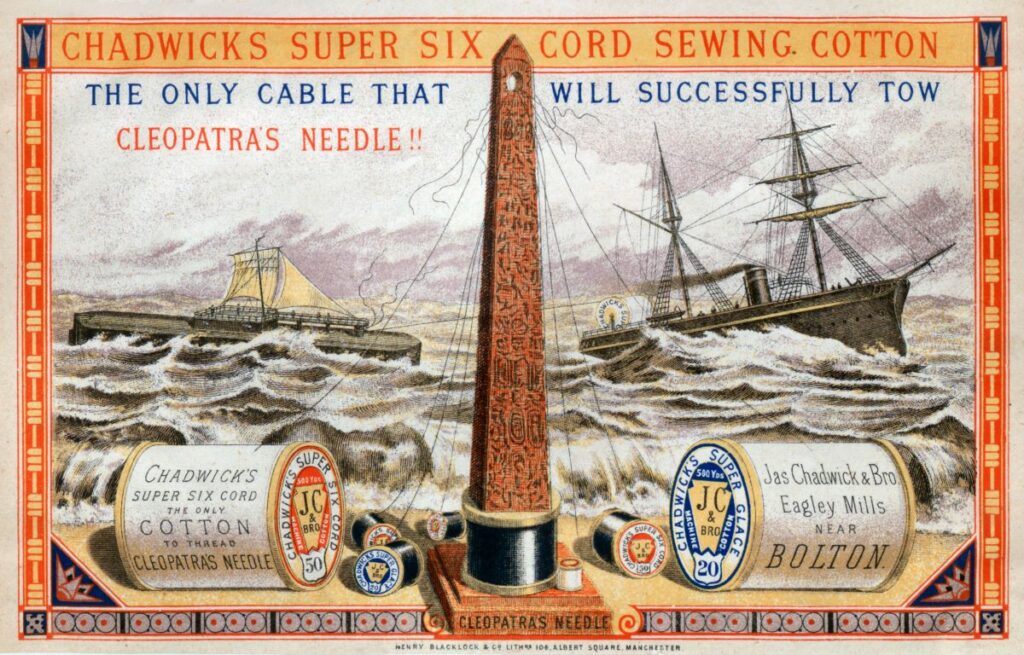

I found the stories about moving the Cleopatra’s Needles from Egypt to London and New York in the nineteenth century spellbinding, involving feats of remarkable ingenuity, danger, and expense. The one now in London was towed across the seas in an ingenious purpose-built contraption that was cast adrift in a storm, but, amazingly, came ashore intact in the Bay of Biscay, and the journey continued on to London. Afterwards, two different makers of cotton thread suggested customers might avoid similar mishaps in their own projects by using their thread! An obelisk craze ensued, with everything from lamps to perfume bottles made in the shape of the mammoth needles. Even a couple of Obelisk Waltzes and an Obelisk March were composed.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 sparked yet another wave of Egyptomania, including the Sphinx realty firm in Los Angeles housed in a building actually shaped like a Sphinx (see Bird’s May 7 Instagram post) and culminating in the Treasures of Tutankhamun traveling exhibition. Any thoughts on that show? Or the state of the Egyptian revival today?

The King Tut show toured museums around the world from 1961 on, but the tour of the US that started in 1976 completely changed how our museums operate, from the blockbuster to the gift shop to the federal legislation helping to insure the objects. It did so much more than just inspire another wave of Egyptian revival.

I am tempted to say that revival styles are a thing of the past, as today’s world seems to want more generic designs that disappear into the backgrounds of our selfies and communicate our taste and wealth in less elevated ways. But if this research taught me anything, it would be that Egypt is always there, quietly waiting for the next permutation of this never-ending revival.

Do you have another “lecture” in mind?

So far, all my Instagram lectures (The Tiffany Diamond Feather, Norman Bel Geddes, some other smaller ones) have started with a puzzle or question that seemed worth investigating and sharing the findings as I went. I have no next topic on the horizon, but I am certain something will come along! I also have more than eighty lectures posted on YouTube.