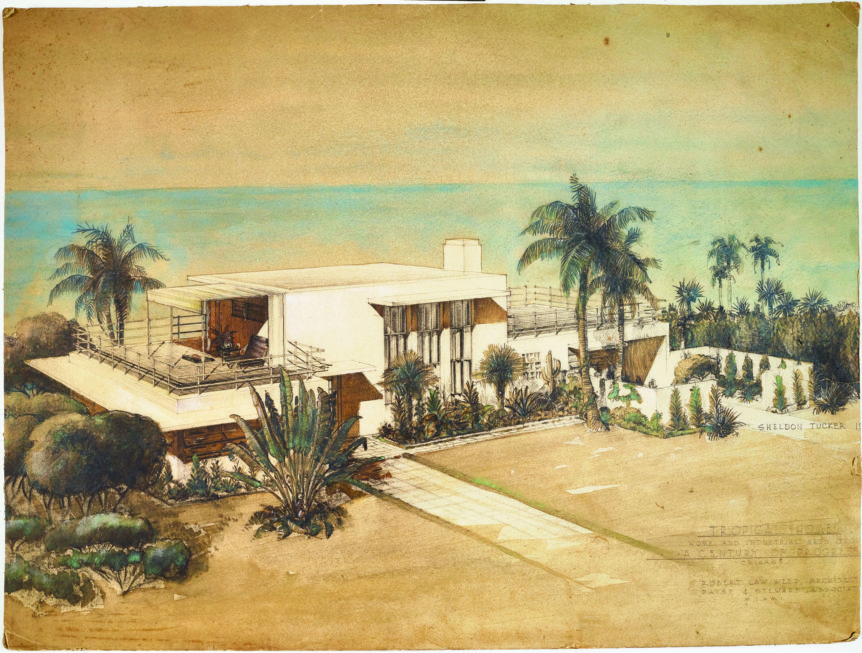

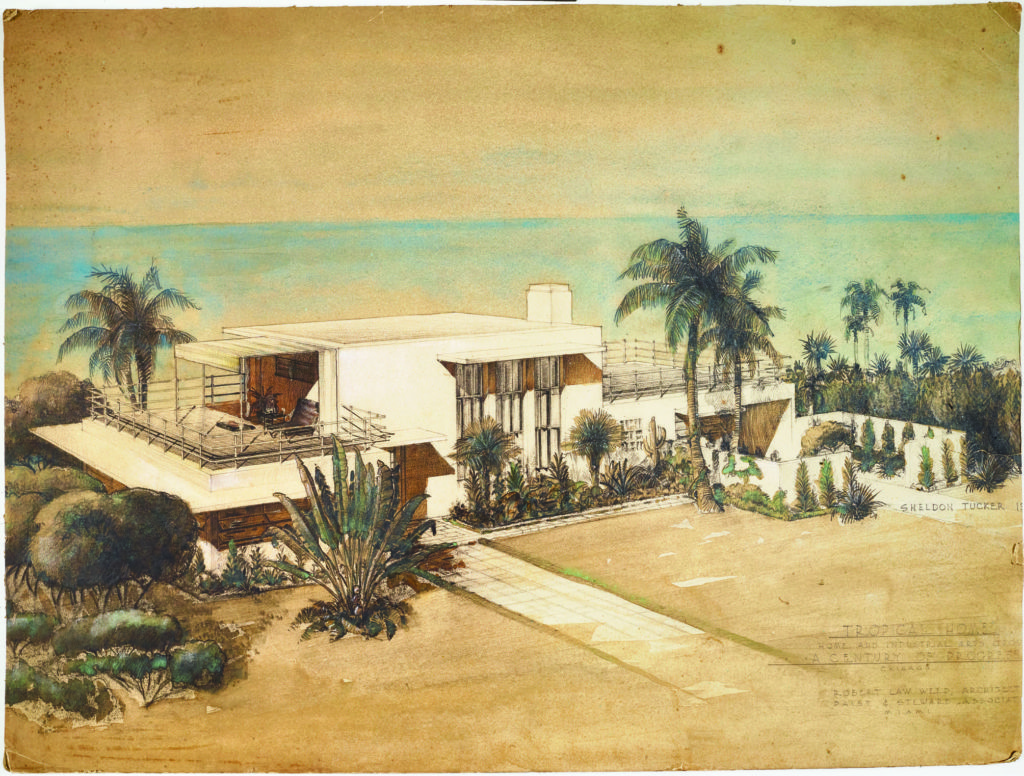

Tropical Home, presentation drawing of the Florida Tropical House, designed by Robert Law Weed (1897–1961) for the Home and Industrial Arts Group, Century of Progress exposition, Chicago, drafted by Sheldon Tucker, 1933. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 18 1/4. by 24 1/8 inches. Wolfsonian–Florida International University, purchased with funds from the Collectors’ Council.

In 1933 Florida Governor David Sholtz wrote that the states various exhibits at Chicago’s Century of Progress exposition were “but the ‘Show Rooms of the state,'” adding, “we further invite you to visit the ‘Play Ground of the Nation.'” 1 The Florida Tropical House, constructed for the Home and Industrial Arts Group section of the exposition and built alongside ten other homes on the shores of Lake Michigan, was one such showroom.

The Florida Tropical House was aspirational, “suiting the taste of the well to do,” 2 and estimated to cost $15,000 to duplicate.3 Miami architect Robert Law Weed designed the home, building a structure that did double duty: an art deco residence functioning as a promotional device for the modern Florida lifestyle.

Key to that lifestyle was the weather. Weed designed for near constant warm temperatures and rainy sea sons. Built of wood with concrete stucco, the home’s cantilevered awnings provide shade and rain protection, while the flat roofs become outdoor areas for lounging and recreation. The numerous entertaining spaces—living room, dining room, multiple terraces— provide opportunity for relaxed socializing, another Florida selling point.

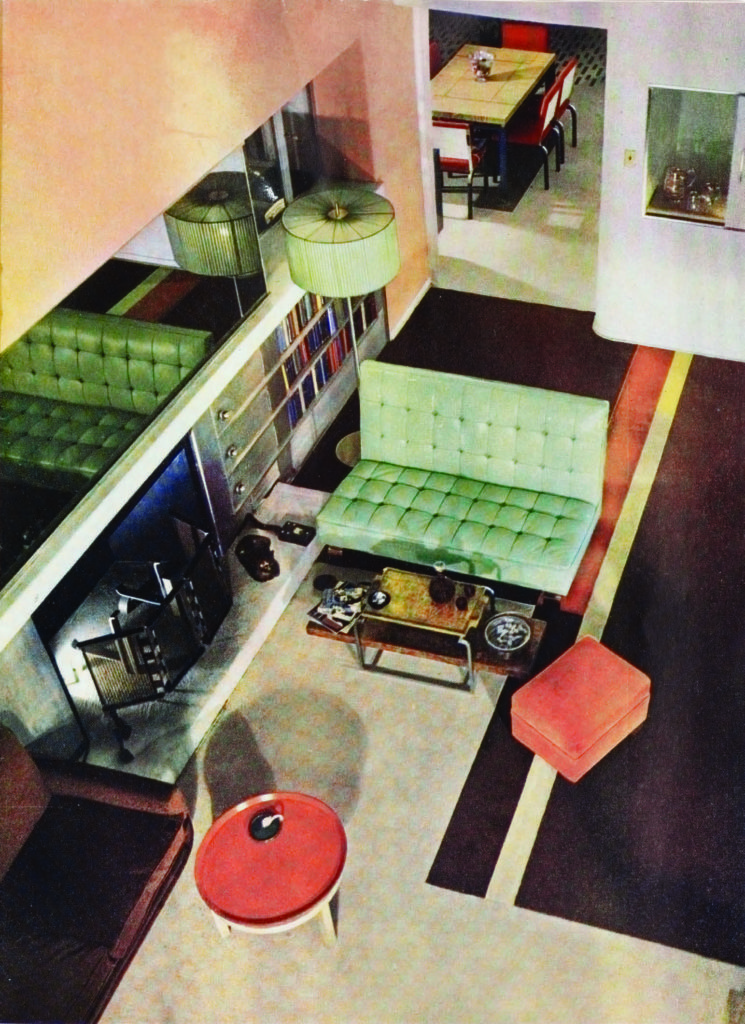

Interior of the Florida Tropical House, photographed by Sarra-Harrer, 1933, as seen in The Florida Tropical Home at A Century of Progress by James S. Kuhne and Percival Goodman.

The clean, streamlined exterior is painted a bright pink inspired by Florida’s flora and fauna. The original interior, too, was colorful, with interior designer James S. Kuhne claiming reference to “the waters of the Bay of Biscayne . . . the health giving rays of constant sunshine . . . the land of play!”4 Kuhne and his fellow designer, Percival Goodman, worked with Ralph H. Widdicomb of the furniture manufacturing firm John Widdicomb Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan, among others, to design the furniture. The dining room suite includes a sideboard made from hardwood, chrome-plated steel, and Bakelite. Veneered in African white mahogany, the sideboard channels the exoticism of European art deco even as the Bakelite handles and stacked disk feet speak to new materials and machine-age design inspiration.

Sideboard designed by Ralph H. Widdicomb (1873–1959), manufactured by John Widdicomb Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, from the Florida Tropical House, 1933. Hardwood, plywood, avodire veneer, chrome-plated steel, Bakelite, aluminum, paint; height 32 1/2, width 36, depth 19 1/2 inches.

The Florida Tropical House promoted Florida as a residential and recreational escape. Meanwhile, Miami Beach—the vacation capital of Florida—took architectural cues from the Century of Progress exposition, with countless hotels built in the mid- and late 1930s that mimicked the streamlined horizontality and neon lighting of the Chicago fair. The relationship between the Florida Tropical House and the fair was circular: visitors to the house would be inspired to vacation in Miami and Miami Beach, which itself looked like the Century of Progress exposition. South Beach’s Art Deco District, the largest collection of such architecture in the United States, is the final legacy of this dynamic.

The Home and Industrial Arts Group exhibition attracted more than 1.5 million visitors to the houses in 1933.5 When the fair concluded, five of the buildings— including the Florida Tropical House were relocated to Indiana and preserved as part of what is now the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Today the Florida Tropical House stands as a record of Florida’s mid-twentieth.century cultural allure and of the enduring architectural impact of the 1933 Century of Progress exposition.

1 James S. Kuhne and Percival Goodman, The Florida Tropical Home at A Century of Progress 1933 (New York: Kuhne Galleries, 1933), n.p. 2 Ibid. 3 Dorothy Raley, A Century of Progress Homes and Furnishings (Chicago: M.A. Ring Company, 1934), p. 54 4 Kuhne and Goodman, The Florida Tropical Home at A Century of Progress, n.p. 5 Kristina Wilson, “Designing the Modern Family at the Fairs, in Designing To morrow: America s World’s Fairs of the 1930s, ed. Laura B. Schiavo and Robert W. Rydell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 143.

SHOSHANA RESNIKOFF is a curator at the Wolfsonian– FIU and a co curator of Deco: Luxury to Mass Market. She received her MA in American Material Culture from the Winterthur Program at the University of Delaware.