The most in-depth biography of the pre-eminent American sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850-1931) is now out. French—whose works include the statues of the Minute Man in Concord, Massachusetts, and Alma Mater at Columbia University in New York—has long deserved a comprehensive exploration, and historian Harold Holzer’s Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French (Princeton Architectural Press, $35) has been eagerly anticipated.

Time in a Bottle

A new book explores the glass collections at Yale University, reflecting the broad sweep of American history in vitreous form

On Books: Rather Elegant Than Showy, the furniture of Isaac Vose

A monumental new study of the life and art of cabinetmaker Isaac Vose

Dropping by the place where Louis dwells

Visitors to Versailles: From Louis XIV to the French Revolution

On books: Damozels & Deities

A new monograph on Pre-Raphaelite stained glass, plus notable museum catalogues from the past year.

Playing against type

At the artful, idiosyncratic publishing house Arion Press, surprise and delight are the stock in trade

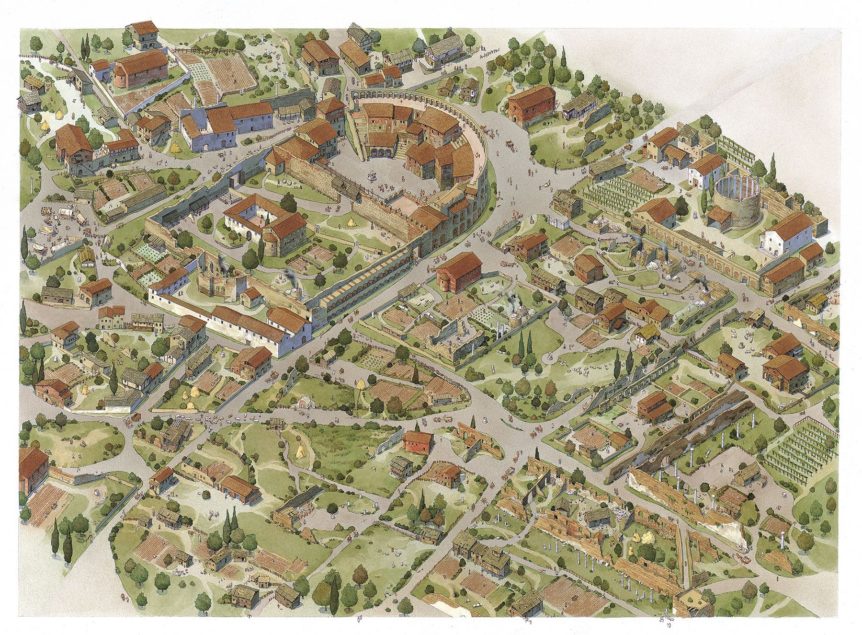

On books: The Atlas of Ancient Rome

It seems to be, or should be, a law of intellectual life that the more obscure a discipline, the better the scholarship that it inspires. Its very obscurity, like a dragon guarding a valued horde, repels all but the most valiant and serious scholars. Compare a Wikipedia article on Khloé Kardashian with one on Pius IX and you will get the idea.

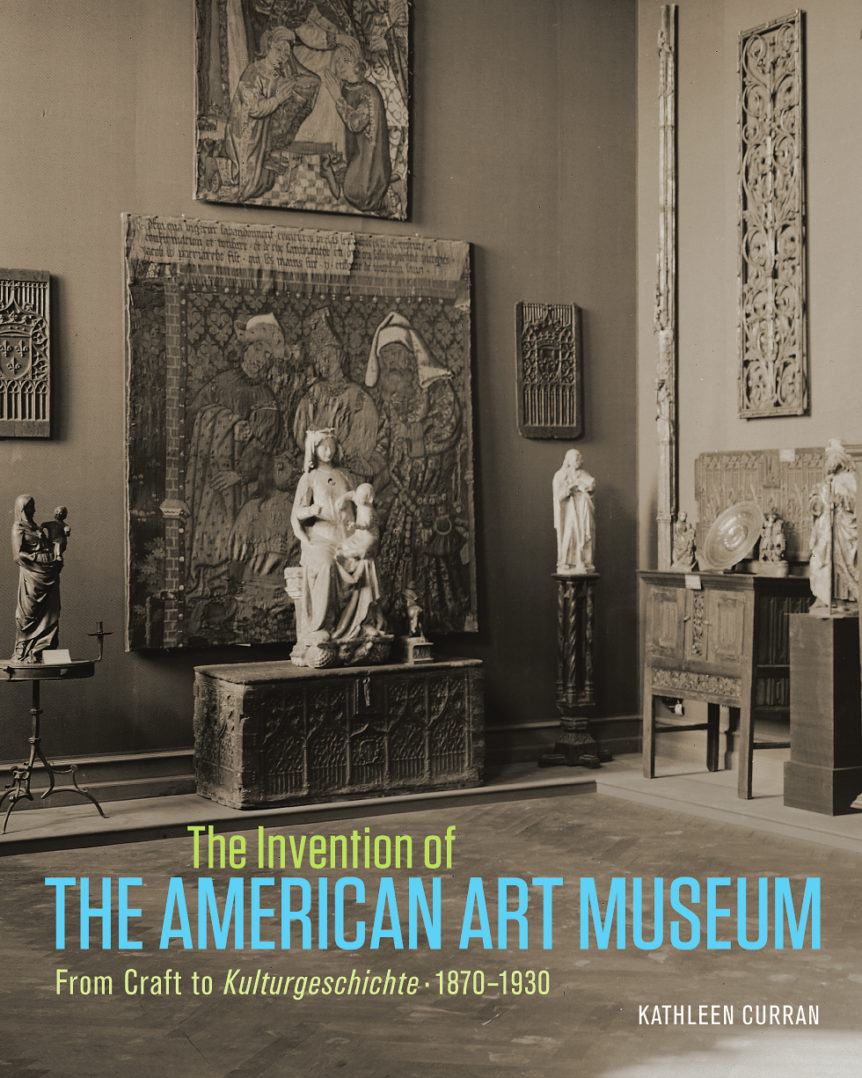

The Invention of the American Art Museum

America is so rich in great museums that we have come to take them for granted. We should not.

Making it Two Authors

Despite our best efforts to be accurate, on the rare occasion something slips through the cracks.

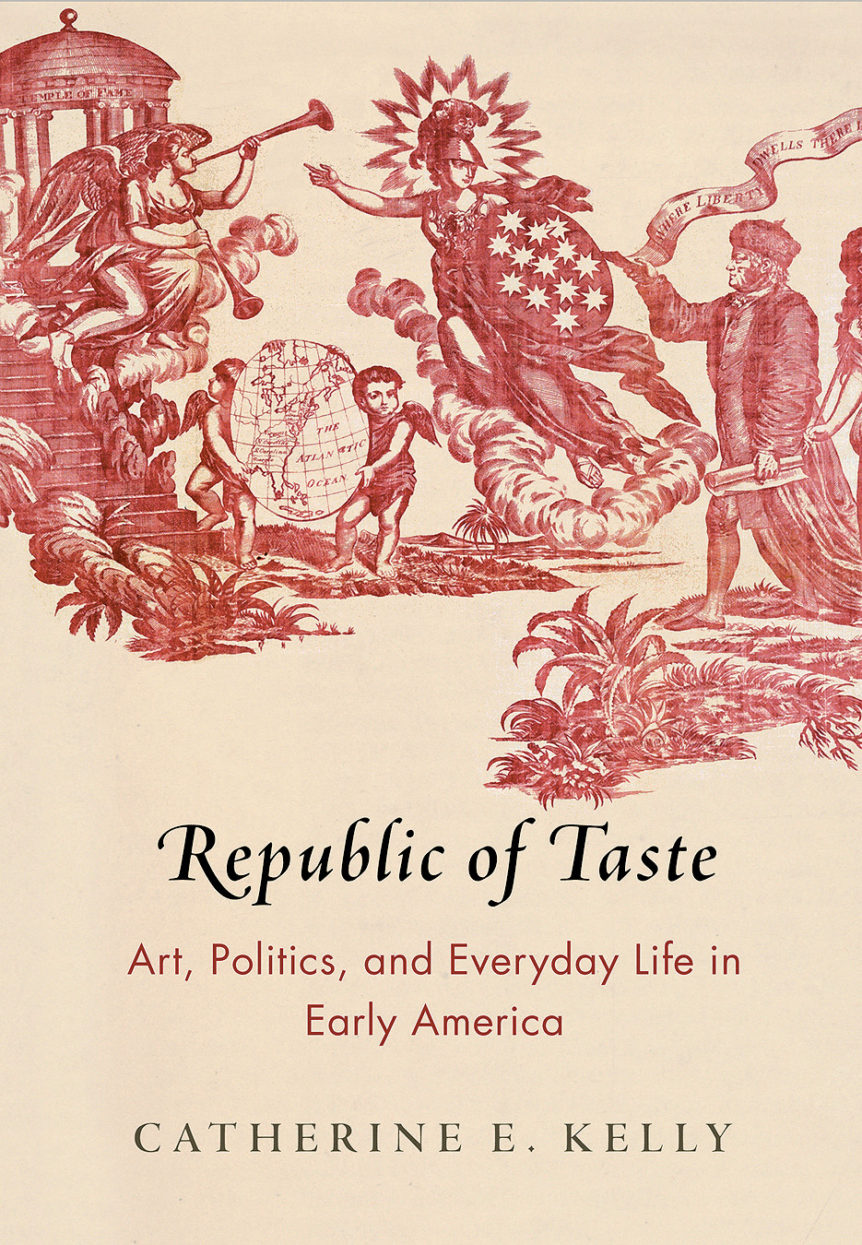

Republic of Taste: Art, Politics, and Everyday Life in Early America by Catherine E. Kelly

Artists and writers in eighteenth-century America, eager to craft a democratic culture distinct from that of Europe, but nonetheless notable for its refinement, elevated the idea of “taste” as an index of character and national virtue. This was not a populist project, but it reached into everyday life through the efforts of the people Catherine Kelly calls “aesthetic entrepreneurs,” who painted portraits, disseminated prints, opened museums, and produced banners and memorabilia to draw the multitudes into a patriotic festival of right-minded taste.